Fakhra Younus was not a familiar name in Pakistan until it flashed across news headlines around two decades ago.

She was 18 years old when she met Bilal Khar, the scion of a feudal family of Punjab. His father Mustafa Khar is the ex-chief minister of Punjab, who styles himself as the ‘lion of Punjab’.

Bilal Khar used to visit Fakhra in Karachi. After six months of courtship, the two got married.

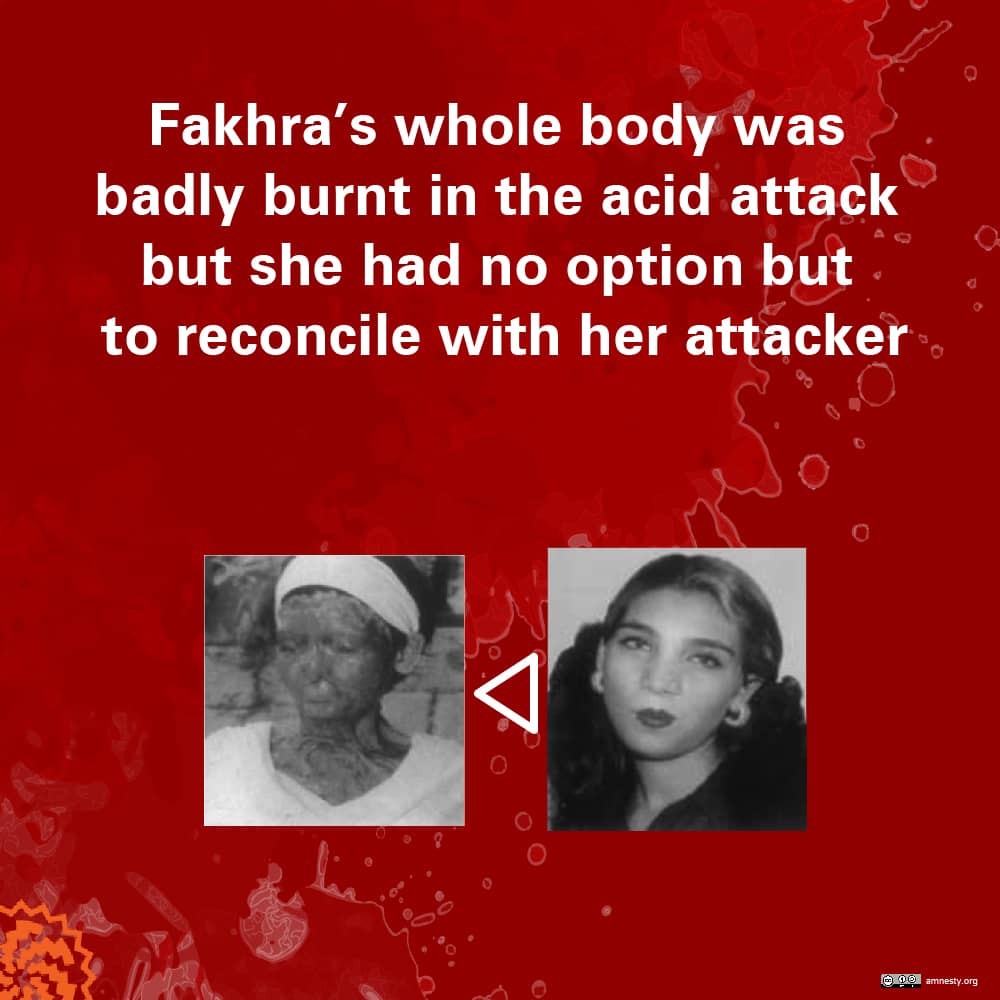

In her interview with the Newsline magazine, Fakhra would later say that he had introduced himself to her as an unmarried customs officer but when Bilal Khar brought her to his home in Lahore, she came to know the truth: he already had three wives. A cycle of abuse, torment and then reconciliation followed after which she finally decided to leave him and go back to Karachi. He, however, chased her down and threw acid on her.

Police arrested Bilal Khar but, Fakhra quoted him as telling her later, he had connections in the police station which explains why they released him after a few hours.

Fakhra’s whole body was badly burnt in the acid attack but she had no option but to reconcile with her attacker. It was Tehmina Durrani, Bilal’s former stepmother, who rescued her from Khar family’s farmhouse and made arrangements for her to escape to Italy.

Back home in Pakistan, the news made to television headlines and, consequently, a trial soon started. Khar family used its political and financial resources to full effect and pressured Fakhra to make an out court settlement. When she refused, the other side bought off her family members who were primary witnesses in the case. They refused to have seen Bilal Khar throwing acid on Fakhra so he was acquitted.

Fakhra committed suicide in 2012 by jumping off the balcony of her apartment in Italy. In her suicide note, she expressed her disappointment at Pakistan’s broken law and justice system.

This is how Zohra Yusuf, the chair of Pakistan's Human Rights Commission, commented on her suicide in an interview with BBC:

"Even in high-profile cases like Fakhra's there are poor prosecutions. Most of the time, victims can't get a case registered by police…only about 10% of cases are getting to court."

‘Saving Face’ and destroying lives

Since Fakhra’s case first became public, acid attacks in Pakistan have attracted considerable media attention. Many documentaries and news reports have been published by numerous platforms that highlighted the gravity of these attacks and the lack of legal recourse available to their victims.

One documentary that stood out among all these was Canada-based Pakistani film-maker Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy’s ‘Saving Face’. Made to humanize the victims of acid crimes, 'Saving Face' shed light on the plight of acid victims in Pakistan while simultaneously capturing the lack of remorse and the lies of their perpetrators. Soon, it won the prestigious Oscar award.

Immediately afterwards, the subjects of the documentary sent legal notices to Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy, asking her to not release her documentary in Pakistan as it could jeopardize their lives in the country.

When the triumphant film-maker returned to Pakistan, she was praised by all and sundry. In a ceremony presided by the then foreign minister Hina Rabbani Khar, the government also gave an award to her. The irony of the occasion was hard to miss: Hina Rabbani Khar is a first cousin of Bilal Khar whose act of throwing acid on his wife was the reason why acid attacks had attracted the media’s attention in the first place.

Then there was another irony: the lives of two primary victims who featured in the documentary,- Rukhsana and Zakia- have worsened in the meanwhile. Even today, little has changed for them. One of them, Rukhsana, is living a shambolic life. She was brutally beaten and was kicked out of her house after the documentary was broadcast. For years, she has been looking for a permanent shelter, struggling to survive with the help of non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Acid Control and Acid Crime Prevention Act, 2011 makes changes in the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) and the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPc) to declare acid attacks not as ‘an attempt to murder’ but as ‘hurt by corrosive agent’

She is currently under hiding with her two children, fleeing her ex-husband who is after her life ever since Sharmeen’s documentary ‘Saving Face’ was released.

Talking to Sujag from a secret location, she says: “My life has become a constant struggle. I do not know who to trust and who not to. I don’t even have the money to buy milk for my children.”

She has also previously alleged that Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy had promised to get her a house, give her three million rupees and arrange her plastic surgery - all in compensation for her role in the documentary.

The way forward

These media-based efforts, regardless of the controversies around them, brought the government’s attention to the heinous crime that acid attacks are. This awareness culminated in a 2012 amendment in the law which recognized acid violence as a crime of a peculiar nature and made it punishable by death.

This law, known as the Acid Control and Acid Crime Prevention Act, 2011 makes changes in the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) and the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPc) to declare acid attacks not as ‘an attempt to murder’ but as ‘hurt by corrosive agent’.

The amendments also make the definition of hurt broader by including ‘hurt by dangerous means or substances, including any corrosive substance or acid burn’. The definitional changes, at least on paper, makes it easier for the victims to have their cases distinguished from ordinary crime. An amendment in section 336-B of PPC increased the punishment of acid attacks to death penalty.

Lahore-based lawyer Chaudhry Waheed, however, believes that these change had very little initial impact. He tells Sujag: “There was no awareness among the police and the judicial fraternity for years so they would not take into account the new amendments when registering cases of acid attacks and giving judgments in them. It took us many years to charge the criminals for the real crime instead of treating their act as a vague ‘attempt to murder case’.”

The ordeal that Raheela has gone through substantiates some other flaws that the law still suffers from. She was subjected to an acid attack in 2015 in Karachi and the hearing of her case has been ongoing for the past five years. Initially, the law enforcement agencies could not even decide which court –the civil one or the anti-terrorism one-had jurisdiction over it.

That said, there is still no law to regulate the sale and purchase of acid. Activists and policy advisors argue that such laws be passed at the provincial levels because after the 18th amendment, the provinces are mandated to make their own laws regarding commerce in such substances.

Sujag has been able to access the draft of Acid Control Bill, 2019 which is doing the rounds in Punjab. This bill aims to regulate the sale, purchase, storage and transport of acid by implementing some government-defined Standard Operational Procedures (SOPs).

Institutional delays and bureaucratic red tape means that this bill is still rotating between the provincial human rights ministry and the law ministry. If and when it becomes a law, it will change many things for the better. Some of its recommendations are as follows:

Also Read

The weapon from hell: 'Every kind of acid is sold freely which leads to many attacks and accidents'

1- Over the counter sale of acid should be prohibited except for medical, industrial or educational purposes;

2- Price of acid should be monitored;

3- No child should be able to purchase acid;

4- No one should be able to buy acid without showing their computerized identity card;

5- Licenses for the sellers must be regularly reviewed by local police;

6- Viscosity of liquid acid should be increased so that it is difficult to throw it on other people

Commenting on the draft, activist and policy advisor Gul Hassan says:

“This is a no-money bill. That means that the government will have to spend no money on creating new mechanisms for its enforcement but use the existing setup.”

Some latest developments suggest that the bill may finally be tabled in the Punjab Assembly soon. The newly formed Women Protection Authority, a forum set up and run by the provincial government, has promised to table it in the assembly in one of its upcoming sessions, inside sources revealed to Sujag.

A new life?

Apart from crime and punishment, the relief and rehabilitation to be provided to the victims of acid attacks is something that can be ignored at the peril of jeopardizing their financial and personal security.

For many victims, such as Razia Bibi and Raheela, the treatment for their burns is an impossible task because it involves expensive procedures like plastic surgeries and skin grafting procedures. For them it will be a great relief if they can lead peaceful and financially secure lives – regardless of whether their physical scars heal or not. Their tormenters are, after all, free to harass and threaten them.

They will be happy if the law can provide them some protection and safety.

As far as providing treatment to acid attack victims is concerned, the government has set up burn units in many major hospitals across Pakistan. Two organizations also have been active in this field for many years, with varying degree of effectiveness. These are Acid Survivors Foundation (ASF) which is based in Islamabad and Depilex Smileagain Foundation which is based in Lahore (you can read Sujag’s investigation report about it here: (Never) smile again.

ASF is Pakistan chapter of the Acid Survivors Foundation International. Its website says: “ASF Pakistan mandate is to work with multiple relevant stakeholders, through peaceful and democratic processes, towards the elimination of acid violence in particular and GBV [gender based violence] at a larger level, and towards the empowerment of survivors -women and children in particular- so that they can exercise their basic human rights.”

While visiting numerous victims of acid attacks in the southern Punjab districts of Multan and Muzafargarh, Sujag found a considerably large footprint of this foundation. Most of the victims that we came across had been treated by it at some point and were still registered with it. The foundation so far also enjoys a positive reputation among survivors, as Sujag’s interviews with them suggest, though some of them complain of delays in treatment which they are told are caused by the paucity of funds and delays in the arrival of doctors from abroad.

Most of the government hospitals do not have the facilities or the equipment that acid burn victims require for the treatment. At the end of the day, the victims will be left with no other way but to go to private hospitals: Suman Ali, Acid attack survivor

Dr Naheed Chaudhry, a plastic surgeon who heads the burns unit at Nishtar hospital, Multan, however, does not believe that any NGO can provide an effective treatment plan to a patient. He says: “If a victim needs fifty surgeries, the NGO might be able to provide only ten.” He also says that providing a total cure to the victim is usually not in the interest of the NGOs as they only get funds by showing how many victims are being treated by them and not by showing how many of them have been cured.

Raheela is also critical of the NGOs: “They are very exploitative and do not allow us to speak against any wrongdoing that might befall us at their hands.” She also tells Sujag that the NGOs “never fund a full face reconstruction as a scarred, rotten face gets them money.”

Apart from these NGOs, successive governments have taken steps to support and rehabilitate the acid burns victims. The most recent among them is the Punjab government’s initiative “Nai Zindagi Program” (A New Life Program) to be run by Punjab Social Protection Authority.

This initiative is expected to simplify the process of getting treatment, among other things. The victims now just have to show a copy of their FIR to be eligible for free treatment at government hospitals. Earlier they also needed to produce medico-legal certificates which are not always easy to procure and can sometimes contradict the stories due to the technicalities involved.

Suman Ali, an acid attack survivor, based in Lahore, expresses concerns about the initiative. She believes that giving funds to government hospitals is a flawed approach as most of these do not have the facilities or the equipment that acid burn victims require for the treatment. “At the end of the day, the victims will be left with no other way but to go to private hospitals,” she says.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 29 Oct 2020, on its old website.

Published on 25 May 2022