Five years ago, Ahmed Nouman, 49, bought a small residential plot on a short, narrow street right outside of Lahore city.

Behind this piece of land was a glamorous gated housing society called Valencia Town and across it was a polluted waterbody with a distinct greyish-black colour. A graveyard on the side, in which malnourished dogs limped around sniffing for food and barefoot toddlers played with plastic waste, connected the two realities.

For Ahmed, this five-marla half-painted brown-walled house is the culmination of decades of hard work. An operational officer in one of Lahore’s largest private schooling systems, he worked day and night for over 10 years to fulfil a dream of owning his own home. Ahmed’s street, and another one like it, are now called Valencia Valley—a housing set-up, spanning over an area of 11-kanal and 18-marla land, with 32 residential structures.

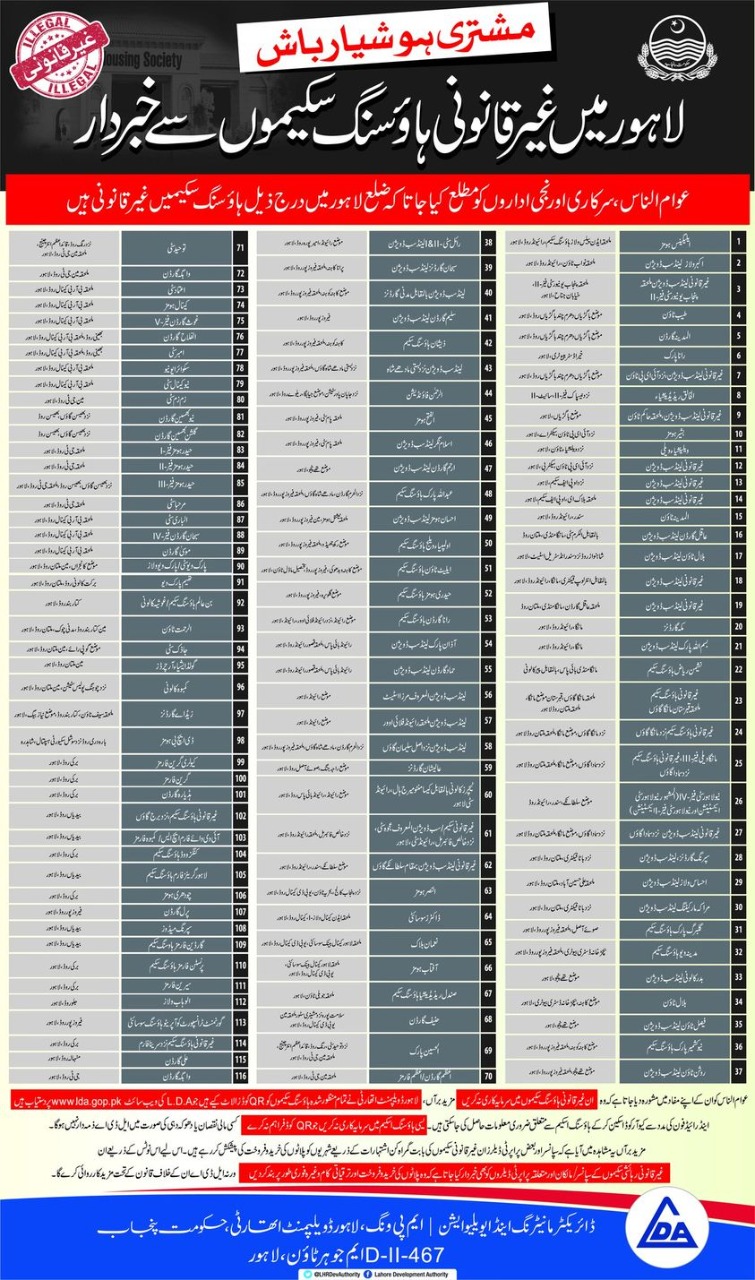

Throwing caution to the wind, the Lahore Development Authority (LDA) declared—through an advertisement published in an Urdu-language daily the Jang on October 7 2022—116 housing societies, including Valencia Valley, illegal. The housing societies, the ad elaborated, did not comply with the set rules and regulations of the LDA. Prominent among them were Manga Valley Phase-III, New Lahore City Phase-IV, Ehsas Villas and Mecca Gardens. The advertisement recommended against investing in these illegal societies.

But advertisements of this nature are not unique; they are published approximately quarterly or biannually. Since the circulation of this advertisement, Lok Sujag has investigated these societies. Approximately 40 of them are categorised as Land Sub-Division (defined as land area less than hundred kanals).

Valencia Valley, a small housing society with 32 residential structures

Valencia Valley, a small housing society with 32 residential structuresMost of these sub-divisions (small societies) are surrounded by larger and wealthier housing societies. Those who live within these small societies come from low-income backgrounds and have used these housing investments as a means for achieving a stable lower-middle class life.

Upon another look, along these developments, is another reality: vanishing villages on agricultural land. And the migration of those villagers into these small housing societies.

The omnipresent class-divide asserts itself through sleek supermarkets and gated entrances alongside vegetable carts and beaten down ‘Welcome-to...’ billboards.

The upper hand

In 2013, the Punjab government sought to create a sole regulatory institution within the Lahore Division—comprising the districts of Sheikhupura, Kasur, Lahore and Nankana Sahib. Through an amendment to the Lahore Development Authority Act, 1975—which was initially passed to supervise housing policies and development—the jurisdiction of the LDA was extended to the whole division.

While previously it was only a district authority, this amendment gave it regulatory control over the entire Lahore division and all housing development within it. Earlier, the TMAs also had the power to approve small-size housing projects.

“When I bought the plot, I had no idea that my society was illegal. I got the land from the landlord who, to my knowledge, had addressed all the regulations and developed the land accordingly,” says Ahmed. He also questions how his society had gotten access to electricity from the Water and Power Development Authority (Wapda)—an institution that requires LDA’s approval for service provision.

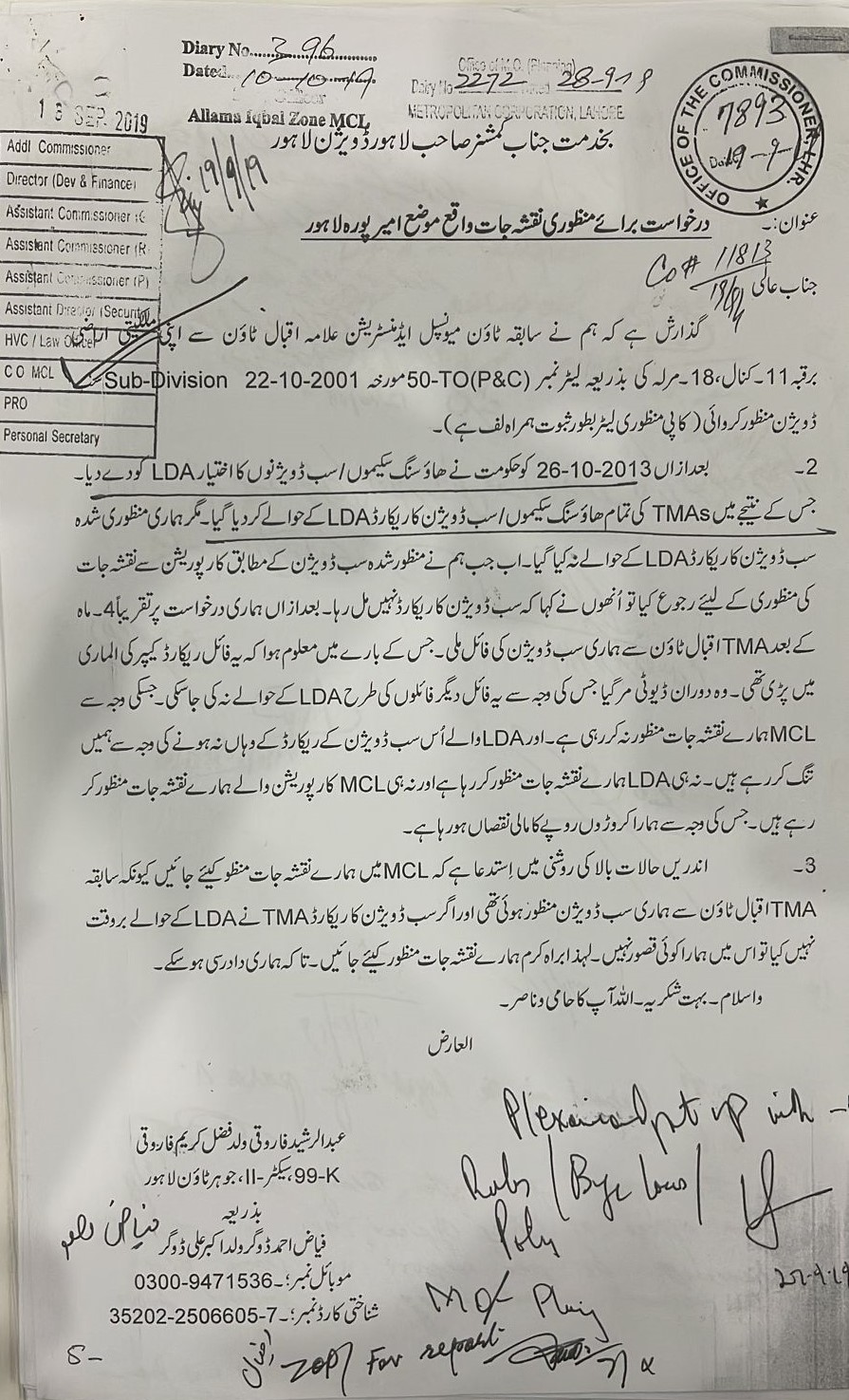

The owner of Valencia Valley, Ishtiaq Dogar, elaborates that this state of confusion has persisted for almost eight years. “When we started working in 2014-15, LDA came and stopped us, saying our society wasn’t approved.” But Dogar argues that he got approval from the then-regulatory body, Tehsil Municipal Administration, in 2011.

When the transfer of power occurred in 2013, the TMA, as per the LDA’s rules and regulations, was duty-bound to send all records—relating to the approval of housing societies—to the LDA within two years.

According to Ishtiaq, LDA was only accepting paperwork directly transferred by the TMA. “I was stuck. TMA had passed our construction map previously but then LDA wasn’t accepting it because TMA had never handed it over to it directly,” recalls Ishtiaq.

At the time, Valencia Valley wasn’t alone in this legal battle. According to Ishtiaq, in 2013, approximately 256 societies were targeted like this by the LDA. “Many societies banded together and took this matter to the Lahore High Court. We submitted an application to the commissioner of Lahore on September 19th 2019.”

The notification issued by LDA mentioning names of illegal housing schemes in Lahore

The notification issued by LDA mentioning names of illegal housing schemes in LahoreWhen the matter, Ishtiaq says, was investigated, they learned that TMA’s record keeper had died during this transfer of power between the LDA and the TMA, and all documents stored under his authority had been lost.

This display of institutional failure, paired with confusion and lack of transparency, is not unique to Valencia Valley—a community that is predominantly made of retired government personnel. These ads are costly too, driving down poor people’s land value.

But unlike Valencia Valley, which is about five years old, many societies within this advertisement have existed for decades.

Tayyib Town was built over 20 years ago. According to many residents Sujag spoke with, LDA ads of this nature aren’t unusual for them.

Nevertheless, the man who sold this land died a while ago. Two decades later, the LDA has proclaimed it illegal, leaving the residents perplexed as to who is responsible for this mess.

A few kilometres north is Al Madina Garden. A wide road—partially accessible due to abandoned construction—leads to the society. Alongside the road are mostly-empty electronics stores and butcher shops. Potholes filled with rainwater over which mosquitoes and flies dance around humans and leftover chicken waste. With traffic flowing in every direction, dust becomes air.

This society used to be agricultural land. The landlord who sold it sectioned off the land into two-to-four marlas small plots and now, years later, it is fully developed. Houses crammed down three lanes, the electricity metres and wiring provided by Wapda creates a visual reminder of their contradictory placement in society: poor, legal and illegal.

Mian Muhammad Ikraam, a local real estate broker, says that by publishing these ads, LDA is driving down poor people’s land value to satisfy and benefit the rich who inhabit in larger societies, nearby. He thinks that since larger societies want to sell themselves as exclusive spaces, they need the land to be scarce and expensive. By having cheaper land nearby, their land devalues.

Thus, Ikraam believes, getting rid of them is the easiest way to protect larger societies. “LDA is not an institution that is accessible to people living in these small societies. If LDA exists to regulate housing societies according to policy standards, then how is it possible that years after societies are built, LDA decides to categorise them as illegal,” says Ikraam.

Application to the commissioner of Lahore for the approval of map for housing scheme

Application to the commissioner of Lahore for the approval of map for housing schemeTo him, this was simply a tactic for LDA to show institutional force once communities are built.

Rashid Mahmood, a director at the Directorate General of Katchi Abadis in Lahore, argues these ads are a way for the LDA to shrug off responsibility. “These ads don’t have any institutional impact and don’t come close to solving the crisis at hand. It is the LDA’s responsibility to provide housing facilities. So, the real question, I think, is: what are they doing to provide low-income housing to poor people?”

Unplanned urbanisation

This display of intimidatory regulatory power by the LDA is happening in sync with a massive housing crisis. A report published in an English-language national daily, the Express Tribune, on May 01 states that Pakistan is witnessing a housing crisis on a scale not seen before.

Correlating with unplanned urban growth, it adds, housing shortages affect 62 per cent of the population. From which a disproportionate majority is low-income. Simultaneously, from 2013 to 2018, the price of a home in Pakistan has increased by 134 per cent. Rent prices have also soared.

These converging crises have not gone completely unnoticed by the government. Last year, the federal government urged the government of Punjab to find a path forward in regularizing more than 6,000 illegal housing societies across the province.

With this objective in mind, a commission was established under The Punjab Commission for Regularization of Irregular Housing Schemes Ordinance 2021. Justice (retd) Azmat Saeed Sheikh was appointed the chairman of the commission, along with other members—Justice (retd) Waqar Ul Hassan and Dr. Shaker Mahmood Mayo.

However, according to Dr. Shaker, who is also the chairman of City and Regional Planning Department at the University of Engineering and Technology Lahore, one of the biggest reasons for lack of institutional management is misplaced priorities. “Small societies should be regularised but LDA cannot be blamed entirely for the lack of policy implementation. We all hold some accountability for the housing crisis in Lahore.”

While he thinks that LDA is not a transparent institution, he believes it hasn’t been given the power to hold the Punjab’s land mafia (another dominant player perpetuating the housing crisis) accountable. He went on to say that the beneficiaries of the current system, the wealthy, don’t want things to change. “Ultimately we can’t compete with them, we can only redirect them in a positive direction.”

In Elite Town—another illegal society located on Ferozepur Road— a resident Mian Aslam questions how large societies, like Rehan Garden Phase-II, continue to thrive without the approval of expansion. “Why aren’t names in these ads? Because if LDA keeps getting paid off by them, they will continue to overlook issues. Poor people don’t have money to buy off institutions,” he says.

One marla in Elite Town, he says, is approximately at 300,000 to 500,000 rupees, depending on location. But a single marla in larger societies approved by LDA, like Central Park, starts from one million rupees. “These small housing societies are the only housing dream that the poor in this country can afford,” says Aslam.

Tariq Lateef—formerly the director of the Punjab Urban Resource Centre which is a non-profit body that attempts to understand urban and development-related issues—has collaborated with the LDA for over two decades.

He thinks that the LDA is “not inclusive.” From planning the areas to regulating and providing services, Lateef draws attention to another important question: how can the LDA be an authority when it’s part of the competition? (LDA has its own housing societies throughout Lahore).

The LDA officials appeared hesitant to talk to Sujag despite repeatedly contacted for getting their side of the story.

Right across Ahmed’s house in Valencia Valley is another small house with a Suzuki Mehran parked outside. That house is owned by Mian Masood Ahmed, a retired railway officer. Two years ago, after retirement, he used his pension money to buy land. During COVID-19, after living in rental housing his entire life, he could no longer afford the cost of living. “In this society, I could construct my own place and pay off the land in instalments instead of wondering if I can afford rent every month.”

As he retreated back to his house, he asks: “We have given our lives to serve this country––what is it doing for us in return?”

Asif Riaz has also participated in the preparation of this report.

Published on 13 Dec 2022