Muhammad Iqbal*calls the business of producing plastic from the waste generated in healthcare centres nali theli – or the pipe and the bag in English. This is because medicine bags, bottles with tubes attached to them and syringes are the main ingredients of this waste.

He says these medical items are manufactured with high-quality ingredients which could be recycled for producing everyday use items such as disposable cutlery, utensils and baby feeders.

Muhammad Iqbal, 45, knows a thing or two about this business as he has been making plastic granules in Lahore for ten years. He says medical waste is cheap so turning it into household items is a profitable business. This waste, according to him, is sold and purchased in many towns and cities across Punjab at 135 to 180 rupees per kilogram. The price of waste stained with blood and other toxic materials is even lower.

He also says recycling of this waste in Lahore is taking place mostly in working class residential areas such as Band Road, Shahdara, Singhpura, Misri Shah and Sanda where people have installed recycling plants inside their houses.

From garbage to plastics

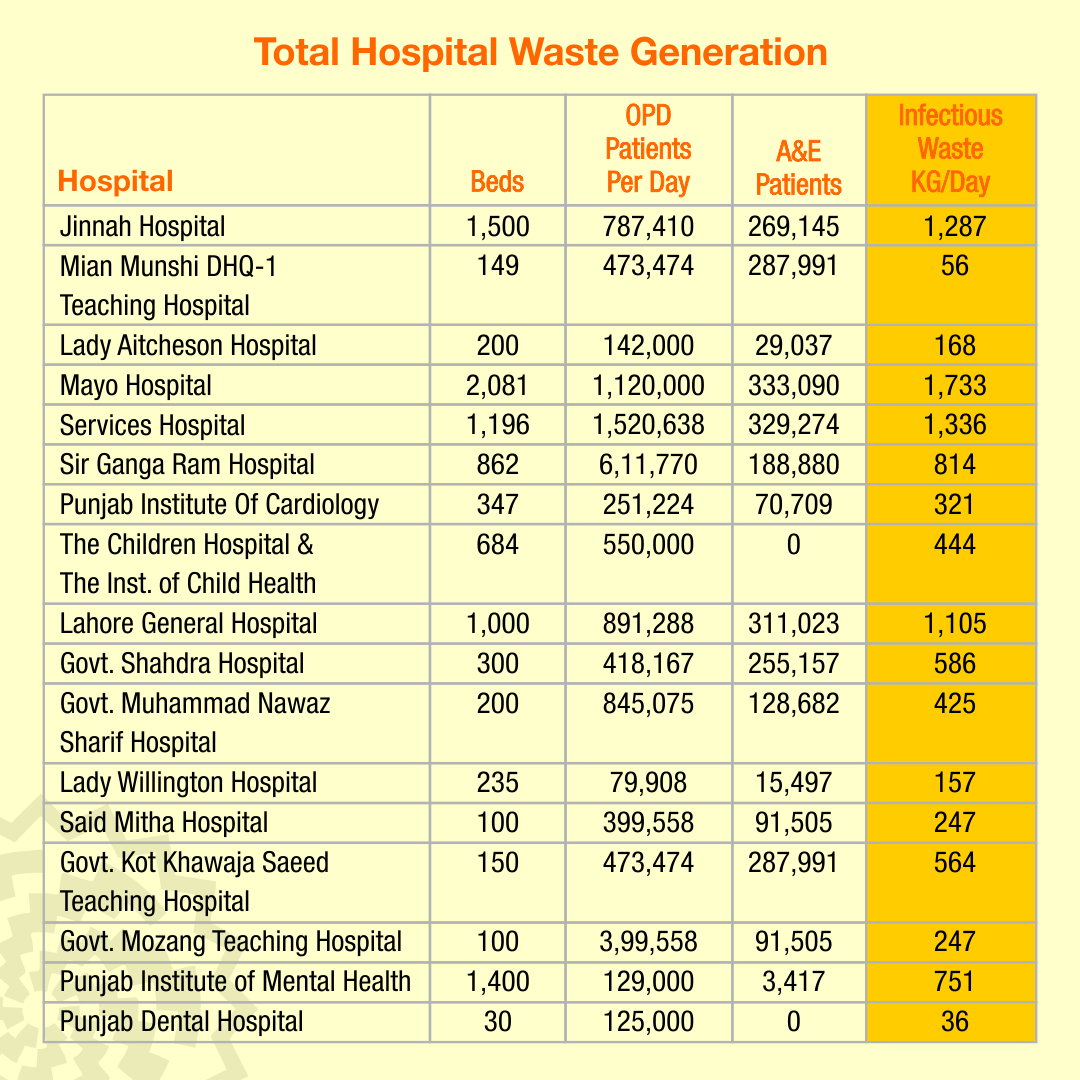

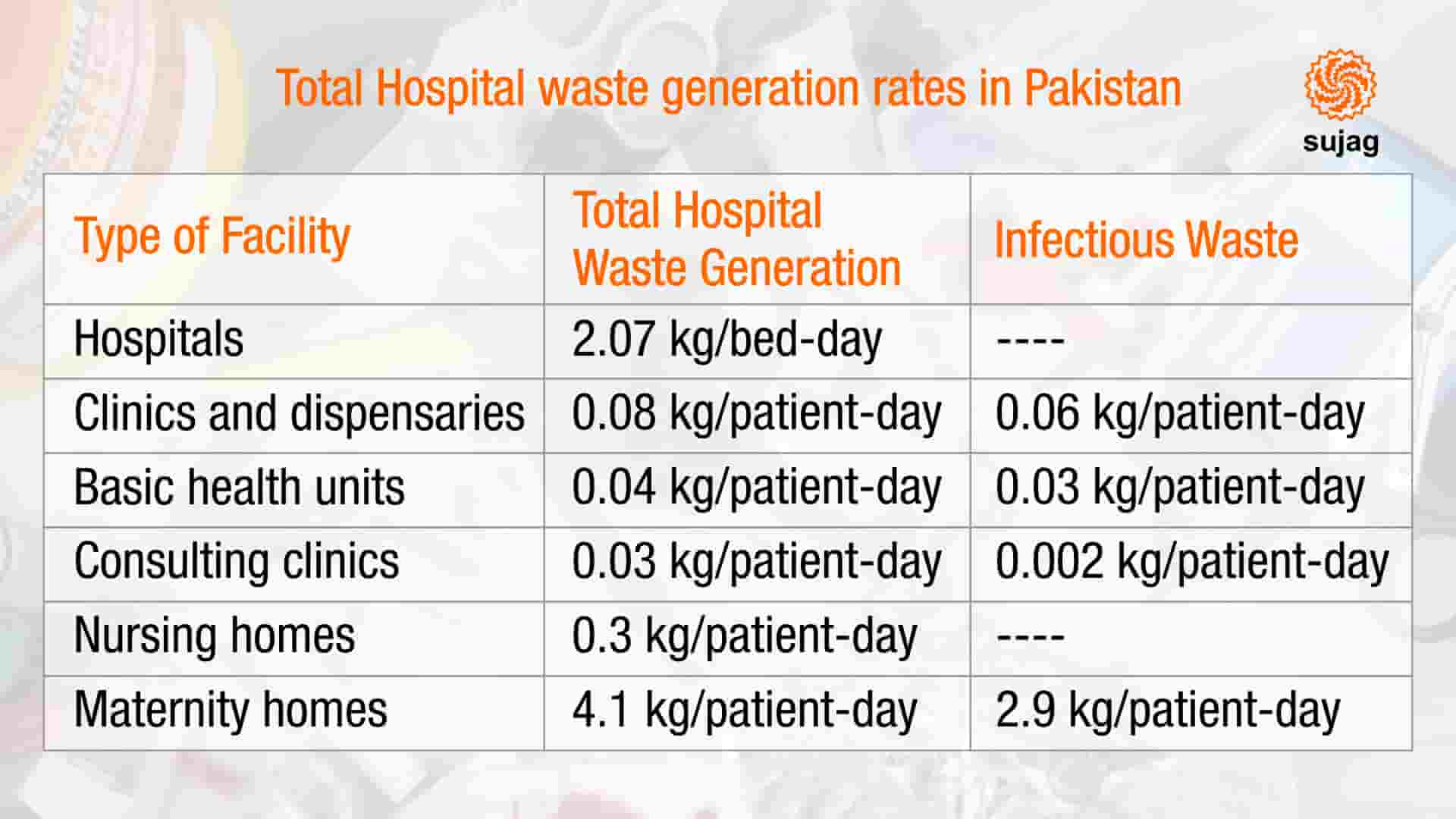

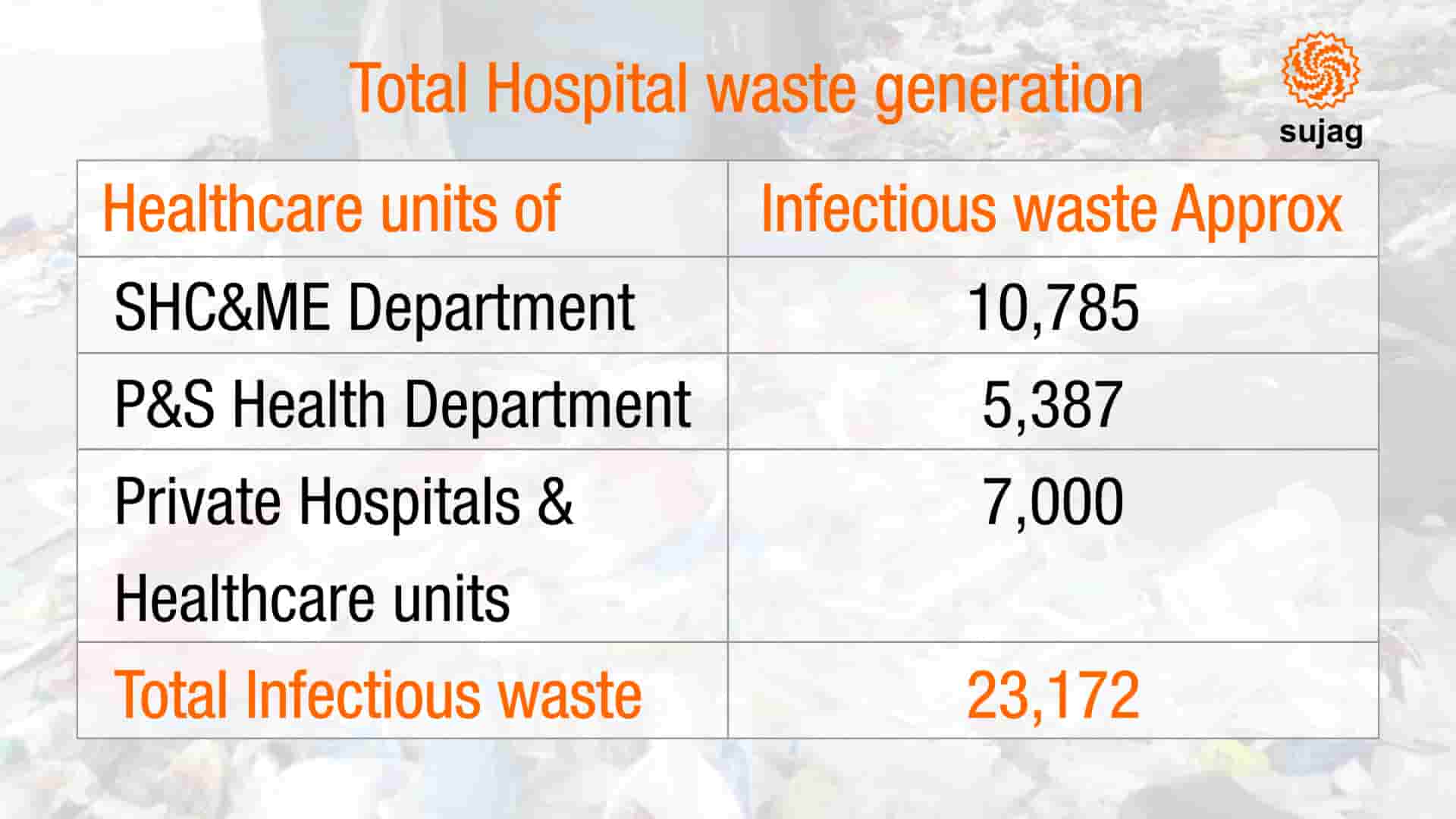

Healthcare centres produce two types of waste: general waste that includes dirt, fallen tree leaves, paper, envelopes, leftover food items and their containers; and the waste generated during medical treatment which is considered harmful (or infectious) for human health. According to the World Health Organization standards, out of every 100 kilograms of garbage generated at healthcare centres, 30 kilograms are harmful and must be destroyed in a scientific way.

This garbage includes surgical instruments, needles, bandages, syringes, urine and blood bags, injection tubes and broken glass vials. It also often contains human organs, blood, bones, flesh, nails and body fluids as well as medicine and chemicals which, if not properly destroyed, can cause diseases.

Healthcare centres in small towns and rural areas are more likely to misuse their medical waste than the similar facilities in large cities because an effective government oversight is often lacking in the former areas. People who make plastic granules say medical waste from other cities of Punjab, including, Karachi is also being brought to Lahore but, before it is transported, it is shredded and crushed into small pieces so it becomes difficult to know its ingredients.

According to Iqbal, “such waste from other cities is easy to use because it is not possible to know without a laboratory test what it really is”. Usually the price of this waste is 200-250 rupees per kilogram.

The sale and purchase of medical waste takes place in Lahore as well though it is no longer happening as openly as it was a few years ago. Instead, it is being done secretly because, according to Iqbal, several government departments within the city now supervise the transportation and disposal of this waste. This drive is being led by the provincial environment and health departments.

Nevertheless, he says, it is not possible for a single individual to turn medical waste into reusable plastic. “It involves a whole gang, including hospital administrators, janitors working at hospitals, garbage collectors and sellers and industrialists who turn waste into plastic goods”.

There has been a lot of evidence of this nexus in recent years.

A major incident in this regard surfaced in 2008 when the City District Government Lahore and the Punjab Environment Protection Department arrested Khalid Shah, a deputy medical superintendent at the Children's Hospital, Lahore, on the charge of selling medical waste by loading it into a truck and moving it outside the hospital instead of throwing it into a local incinerator.

Similarly, 25,000 bags of medical waste were seized from a factory in Malipura area of Lahore in April 2009 after the National Accountability Bureau (NAB) discovered them there. In September of the same year, Multan’s deputy commissioner and the Punjab Environment Protection Department filed a lawsuit in a local environmental tribunal alleging that Dr Mushtaq Ahmad, president of the organization responsible for disposing of waste generated by private medical centres in Multan, the Association of Hospitals for Safety Measures Advances and Nationals, should be prosecuted for fraud.

The organization was set up several years ago by doctors running private hospitals and clinics in Multan and was collecting medical waste from around hundred local healthcare centres in 2019.

According to newspaper reports, instead of burning the medical waste safely, it was selling plastic items in it which were later taken to Lahore for making feeders, utensils and beverage straws.

Dr Ashraf Nizami, president of the doctors’ organization, the Pakistan Medical Association, in Lahore, also confirms that the transportation and disposal of medical waste is not being monitored properly. The problem, according to him, starts during the segregation of medical waste from other waste at the hospitals. “Some people steal this waste during that process with the connivance of hospital staff”, he alleges.

Who is in charge?

Muhammad Ifrahim *, 30, is sitting in a small compartment with its door closed to avoid the stench emanated from the medical waste burning in the adjacent incinerator. Some surgical instruments are lying in his room which he has taken out from the ashes of the burnt garbage. Several wires and other metallic objects are also lying around him because these could not burn in the incinerator.

The facility is located in a rural health centre in the Gujranwala division. Ifrahim is its operator.

The incinerator room has a scale which is used for weighing the waste. After recording the weight in a register on a daily basis, Ifrahim reports it to the head office of his company, Mede land Pakistan, based in Lahore.

Dozens of yellow bags are lying in a room next to the incinerator. They carry stickers showing where they have been sent from.

Ifhraim says the waste in the bags could not be burned because the incinerator could not run for two days due to the non-availability of gas. According to him, the incinerator has a burning capacity of 100 kilograms per hour but “at present we burn 50 to 70 kilogram of waste in an hour”.

Ifhraim complains that ordinary garbage and medical waste are not separated properly before they reach him. Ordinary plastic bottles, glass bottles, iron and other metal materials could be easily found in large quantities in medical waste, he says. According to government regulations, however, only harmful medical waste should be burned in the incinerators.

Although such incinerators have been set up all over the Punjab, according to Professor Nizami, there are only two of them in Lahore. One of them is at the Children's Hospital (but it is in a dire need of repair) while the other is at a private medical centre, Shalimar Hospital.

To improve this situation, a public sector organization, Lahore Waste Management Company, submitted a proposal to the Punjab Planning and Development Department in June 2017. This proposal delineated arrangements needed to be made for a scientific disposal and proper collection of medical waste from all the major hospitals in Lahore. The cost of the project was estimated at 178.4 million rupees.

The Planning and Development Department approved it but, according to the spokesman of the Lahore Waste Management Company, it could not go ahead because the Punjab Health Department wanted to implement it on its own.

In the absence of this plan, medical waste disposal is being carried out under the rules and regulations laid down in 2014. Under these rules each hospital and medical centre outsources the disposal of the waste to a private company.

According to Professor Nizami, there are two major weaknesses in this arrangement. Firstly “yellow rooms and yellow bags have been made available in every government hospital for the collection and storage of the hazardous waste but there is no scientific system to separate hazardous medical waste from the ordinary waste”. Secondly “no procedure has been laid down for monitoring the contractors”.

An important revelation in this regard was made in 2019 when the National Accountability Bureau (NAB) submitted a report to the Supreme Court of Pakistan in which it said that Ali Traders Waste Management firm, a company operating in Punjab’s hospitals, was not disposing medical waste in a scientific way but was making money from it by recycling it fraudulently.

In August 2020, NAB also arrested the company's chief executive Muhammad Naseer. He is accused of colluding with three officials of the Environment Protection Agency to increase his company's capacity to burn medical waste from 100 kilograms to 400 kilograms per hour without installing any additional machinery.

Despite the arrest of its chief executive, Ali Traders Waste Management Company is still disposing the government hospital waste. Its representatives, Gulfam Shehzad Advocate and Raja Tahir Mehmood, say they will not discuss the matter as “our case is in a court and any of our statements could affect it”.

On the other hand, the spokesman of the Punjab health department, Hamad Raza, says the existing contracts of the company have not been terminated because the case against it is still under investigation. “We will provide whatever information the investigating agency or the court wants from us in this case and we will also implement whatever decision the court makes”, he says.

* Names have been changed for anonymity.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 6 Feb 2021, on its old website.

Published on 27 May 2022