Prior to the partition of India, the subcontinent’s British rulers preferred that their subjects articulated their family affairs in accordance with their customs and traditions. This was because of the fact that people of different faiths living in the subcontinent followed different cultural traditions and religious edicts for regulating marriage, divorce, inheritance and other family matters.

The British rulers, thus, converted the traditions and edicts governing these subjects among Christians and Hindus into some laws. Of particular importance in this regard are the Christian Divorce Act of 1869, the Christian Marriage Act of 1872 and the Hindu Heritage Act of 1929.

In the first three decades after the creation of Pakistan, the same laws were followed in the country with almost no changes. In the early 1980s, during Ziaul Haq’s military government, however, a significant change was made in some of these laws for the first time.

Following is a chronological description of the attempts made to amend or reform the laws governing marriage, divorce and inheritance among Christians, Hindus, Sikhs and Kailash living in Pakistan.

Changes in Christian family laws

Family laws for Christians in Pakistan are more or less a continuation of the Christian Divorce Act of 1869 and the Christian Marriage Act of 1872.

The Divorce Act allowed Christian couples to leave each other if one of them was committing adultery, had remarried or was involved in a rape. They could also divorce each other if one of them had changed their religion.

In January 1981, the military government of then President Ziaul Haq revoked Section 7 of the Divorce Act. After this change, separation between Christian couples was legally possible only if one of them was proven to have committed adultery.

In 2011, National Commission on the Status of Women drafted a number of laws after reviewing various objections to the Christian divorce law but the government was unable to present and pass these drafts in parliament.

In 2012, an oversight committee of the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women suggested in its review that Pakistan needed to reform its Christian marriage and divorce laws.

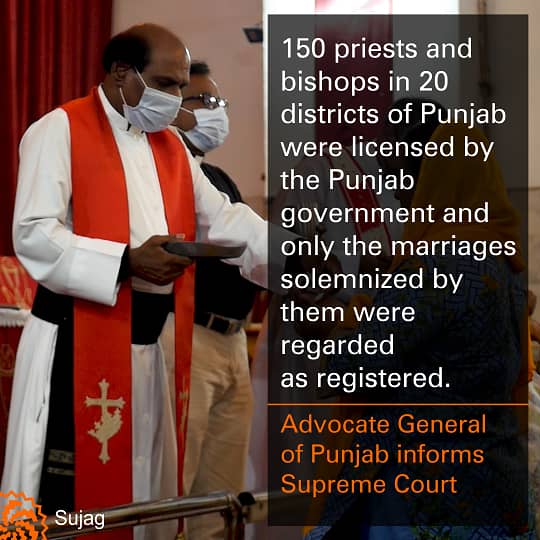

During the hearings of a suo moto notice in 2013, Advocate General of Punjab informed the Supreme Court that 150 priests and bishops in 20 districts of Punjab were licensed by the Punjab government and only the marriages solemnized by them were regarded as registered.

In 2014, the federal government drafted a law to amend the Christian Marriage Act 1872 and the Christian Divorce Act 1869 but no further progress could be made.

In January 2015, a man named Amin Masih filed a petition in the Lahore High Court saying that he wanted to leave his wife but did not want to accuse her of adultery. The petition contended that, in the absence of section 7 of the Christian Divorce Act, it was not possible for Christian couples to give or obtain divorce if they were incompatible with each other. Amin Masih asked the court to reinstate this section so that the process of divorce could be made easier for Christians.

On the occasion of International Women’s Day in March 2017, the then Punjab Chief Minister Shehbaz Sharif announced that Punjab Assembly would amend Christian family laws.

In May 2017, the government of Pakistan submitted a written declaration of commitment for the protection of human rights to the United Nations Office before being elected as a member of the UN Human Rights Council for two years. The declaration stated that amendments will be made to Christian family laws in the country.

In Jun 2017, Justice Mansoor Ali Shah of Lahore High Court ruled that Section 7 had been deleted by an undemocratic government. He also stated that Christian churches and/or Christian religious leaders had not been consulted during the process of removing the section. He, therefore, declared its removal as unconstitutional.

After its restoration, Christian women no longer have to face the charges of adultery in order for their husbands to divorce them.

In the later part of 2017, an intra-court appeal was filed against Justice Mansoor Ali Shah’s decision. This is pending hearing before a division bench of the Lahore High Court.

In 2017, federal ministry for human rights sent two bills to the federal law ministry for corrections and revisions. These bills sought to amend the Christian marriage and divorce acts. After their review by the law ministry, they were to be presented to the cabinet.

In September 2019, the federal cabinet approved these drafts but the Christian clergy said that it was not consulted before the approval and that some of the provisions in the drafts contradicted religious precepts.

In February 2021, federal minister for human rights Shirin Mazari announced that the government had drafted a bill to amend the Christian marriage and divorce acts which would soon be presented in the National Assembly.

In 2021, two citizens, Shehzad Francis and Sabir Michael, filed a writ petition at the Islamabad High Court against Section 10 of the Christian Divorce Act. Under this section, divorce can only take place if one of the spouses has committed adultery. The petition is being heard by Justice Athar Minallah, the chief justice of the high court.

Changes in the family laws of Hindu, Sikh and Kailash communities

After the partition of India, no procedure could be devised to register marriages and divorces of Hindus living in Pakistan. Consequently, Pakistani Hindus faced many social and legal problems. Scheduled caste Hindus were particularly affected by these problems.

They, for instance, have been facing difficulties in obtaining jobs, identity cards, passports and domiciles. They were also experiencing hurdles in the registration of their votes and the enforcement of their inheritance rights.

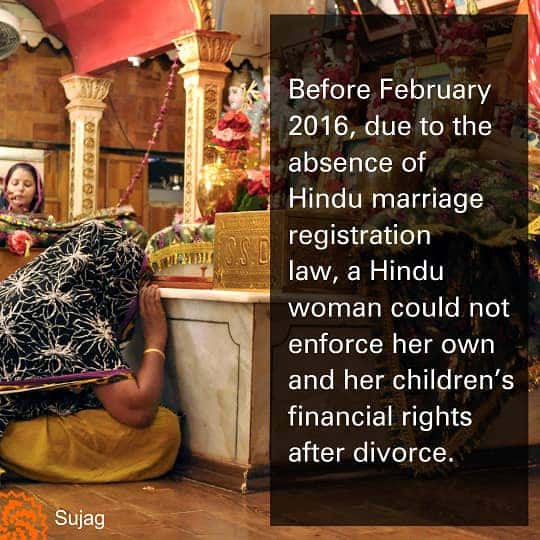

In 2000, Guddi Mai, a woman from Rahim Yar Khan, petitioned a local court that, due to the absence of Hindu marriage registration law, she could not enforce her own and her children’s financial rights after her husband had divorced her. Her former husband, indeed, had refused to recognize her as his wife and she had no documents to prove that she had remained married to him. Her plea was accepted by the court which ruled that a law should be made for the registration of Hindu marriages and divorces.

In December 2008, Hare Ram Foundation, a Hindu organization, submitted a draft law to the government of Pakistan on the registration of Hindu marriages and divorces and demanded its immediate passage. The then federal minister for minority affairs Shahbaz Bhatti assured the organization that the legislation in this regard would be done within three months.

In January 2015, a woman named Sonea Talreja filed a petition in the Lahore High Court in which she contended that a 1929 law – also in force in Pakistan -- regarding the distribution of inherited property among the members of a Hindu family was based on the customs of ancient times and preferred men over women in terms of inheritance. This, she pleaded, was unconstitutional because, as per Pakistan’s constitution, no one can be discriminated against on the basis of gender. Referring to India in the petition, she stated that there an amendment was made in the British-era law in 1956 to eliminate discrimination between men and women in matters of inheritance. So, she pleaded, a similar legislation should be passed in Pakistan as well.

In February 2016, Sindh Assembly passed the Hindu Marriage Law presented by Nisar Ahmad Khuhro, the then provincial minister for parliamentary affairs. The law provided that Hindu men and women aged 18 and above and living in Sindh could voluntarily marry and have their marriages registered. The act also provided for the registration of marriages of Sikhs and Zoroastrians.

In September 2016, National Assembly unanimously passed the Hindu Marriage Act which provided for the registration of Hindu marriages. The act was presented by Kamran Michael, the then federal minister for human rights. According to this law, a man and a woman must be 18 years of age or older at the time of their marriage. If a couple has been separated for a year or more and wanted to end their marriage, the law provided for the annulment of their union. The law also allowed the separated couple to contract second marriages six months after that annulment.

The law has made the violation of the rules governing the registration of Hindu marriages as a punishable offense which can attract a sentence of six months. It also provided that a Hindu man or a woman cannot remarry while his/her first marriage is intact. Those violating this provision could be punished by a court of law.

Also Read:

Unhappily ever after: ‘I keep asking him for a divorce but he never obliges’

In March 2018, Punjab Assembly unanimously approved the Sikh Marriage Act. It is also called the Punjab Sikh Anand Karaj Act. According to its provisions, the marriage of a Sikh boy or a girl below the age of 18 will not be registered. The law also prohibited Sikhs from marrying in their father’s family and stated that no marriage will be legal unless the marrying couple has taken four rounds together and their marriage has been registered in accordance with the teachings of Sikh holy book, Granth Sahib.

In May 2018, Sindh Assembly passed the Hindu Marriage Amendment Act which allowed Hindu women to remarry six months after the death of their husbands. The amendment also allowed Hindu women to seek a divorce and guaranteed financial security to mothers and children after a divorce. The amendment was presented in the provincial assembly by Nand Kumar Goklani of the Pakistan Muslim League-Functional and was passed unanimously.

In October 2020, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government announced that it will introduce the Kailash Marriage Act to protect the traditions and culture of the Kailash community with regard to marriage, dowry, divorce and inheritance.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 23rd June 2021, on its old website.

Published on 18 Feb 2022