Nothing looks unusual around Bosal village in Mandi Bahauddin district. It has the same look that almost every place in this part of central Punjab has: Irrigation canals passing by human settlements surrounded by fruit-laden orchards and tree-lined crops -- as far as one can see.

Deep inside this predictably uniform setting lies something utterly unexpected: A Hindu family living in a farmhouse since the pre-partition days. Their residence, Haveli Divan Chand, is located around five kilometers to the north of Bosal and could be mistaken for any rundown building left behind by its inhabitants when they migrated to India in 1947 – except that those living here have stayed put.

Sapna Kavita Oberoi, the oldest living resident of the haveli, says her grandfather, Divan Chand Oberoi, had built it many years before the partition. He was an engineer by training but ran a trucking business. In August 1947, she says, army used his trucks for transporting Hindu families living in and around Bosal to the other side of the newly demarcated border between Pakistan and India. Divan Chand and his young son, Sardari Lal Oberoi, were travelling in the last truck to leave the area when they were attacked by a mob. “My grandfather was hit by a bullet in his throat,” Sapna says. The truck had to be turned back to treat his wound.

Divan Chand would survive the attack and Sardari Lal would later marry Kiran Sawhney, the daughter of a lawyer, Inderjeet Sawhney, whose family had also stayed in Pakistan after the partition. The Sawhneys originally lived in Salam village where Lahore-Islamabad motorway has an interchange but Inderjeet’s father Mohan Lal Sawhney had also built a house in Sargodha city.

Sapna is the oldest daughter of Saradari Lal and Kiran. She has two more siblings: A sister and a brother. Together, the three of them own a large tract of agricultural land in their native area – 125 acres – where they grows many crops and fruits.

Sapna says both her parents have died recently though she has been the public face of her family even when they were alive.

She has been a member of Faisalabad Chamber of Commerce and Industry and an executive member of Kinnow Growers Association, Sargodha, for many years. As the representative of her family business, Oberoi Traders, she has travelled to many countries, including India, to participate in trade and industry exhibitions.

More than 50 years old now, Sapna is still unmarried. She says she chose to stay single because she “never wanted to leave her mother”. Her younger sister also did not marry – and, according to Sapna, for the same reason. This is also, in her words, the reason behind their aversion to leave the rural backwaters of Bosal and move to a city or to another country.

“Even if I wanted to marry,” she says, “my choices would have been limited”. She could not have married in the offspring of her maternal grandfather some of whom still live in Lahore and Sargodha because Hinduism prohibits marriages among near and distant cousins. “I would either have to convert to Islam or move to India or find a spouse from Sindh [where a majority of Pakistan’s Hindus reside],” she says.

Conversion was never an option for her – so was moving to India – since both would have forced her to leave her mother. She could have found a suitable partner in Sindh but then it, too, would have involved leaving her mother and could have also caused some caste-related complexities.

In terms of Hinduism’s rigid caste categories, Sapna is a Kshatriya (who are known to be rulers, courtiers, warriors and farmers). Although thousands of Kshatriya live in Sindh, their religious history and conventions are very different from the religious history and conventions of Punjabi Hindus like the Oberois and the Sawhneys.

“It is difficult for Hindus to marry outside their caste and across religious boundaries. Their families will never approve of that, especially if they marry someone below their social, religious and caste status,” she says.

Her brother faced the same problems but, as she says, his parents and sisters supported his marriage to someone not strictly falling within the boundaries laid down by religious conventions and the caste system. He now has two young children who will one day inherit the haveli built by their great grandfather.

Without familial support, Sapna’s brother, too, would have remained unmarried. He, indeed, had no other religious and legal avenues to find a wife given that there are not many Hindus living in central Punjab and also given that Pakistan does not have a law that allows adult Hindu boys and girls to marry anyone they want, regardless of caste and creed.

If nothing else, his singlehood would have jeopardized the future of his family’s large land holding and other assets.

Subtle pressures to convert

Around 70 kilometers to the southeast of Haveli Divan Chand is the lush village of Doda. Before 14th August 1947, it had a sizeable number of Hindu residents who were persuaded by their neighbors to not give up everything and migrate to India. Since then they have experienced a gradual decline in their population, most of them having converted to Islam over the last seven decades. Madan Lal has become Ibrahims and the village that housed more than 50 Hindus only a couple of decades ago, now has less than 20 of them.

The pressures on Hindus of Doda to convert have been more covert than overt. With no institutional arrangement to instruct their children in Hindu rites, rituals, history and conventions, they were exposed to a Muslim-dominated educational, economic and cultural milieu to such an extent that their bonds with their own religion became tenuous over time. After one of them converted a couple of decades ago and became a Muslim preacher, the rate of conversion among them picked up pace.

Unlike in Sindh where Hindus enjoy a sizeable political and economic clout, the few Hindus living in central Punjab’s villages could have done better if the state had provide legal protection to their religious and cultural conventions – as the constitution guarantees. In the absence of that protection, they are finding it difficult to even sustain their family lines.

Ami Chand, whose name has been changed by his Muslim acquaintances to Ameen Chand to make it sound a little less Hindu, works as a veterinary dispenser in Doda. As the informal head of Hindu community living in the village, he has seen his own cousins and brothers convert to Islam in recent years. Those who still stick to the religion of their ancestors, he says, are facing many problems.

On a recent June day, he is sitting at his veterinary dispensary located beside a cremation site strewn with wild plants. “We usually bury our dead here,” he says pointing to a few graves and an unkempt tomb next to his workplace. Those who leave behind the instruction that they be cremated are taken for their last rites to Nankana Sahib where the founder of Sikh religion, Guru Nanak, was born.

The other major problem confronting his community concerns marriages. While it is becoming increasingly difficult for them to find matches for their children, they also do not find it easy to have their marriages performed in accordance with their religious traditions. Since there is no Hindu temple nearby, they have to fetch a pundit from as far as Lahore to do the job. And since most of them are small farmers, they often do not have enough money to pay for the pundit’s travel, boarding and lodging.

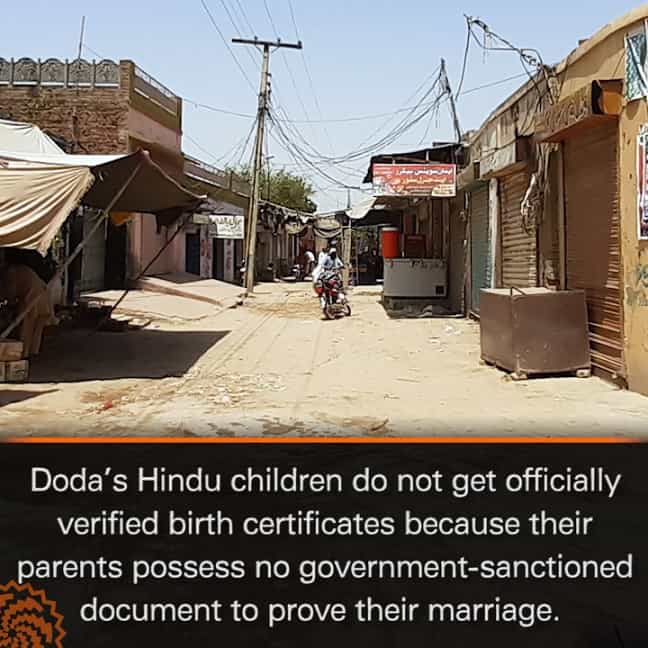

Even when they manage to jump over or sidestep this hurdle, they do not know how and where they should get their marriages registered. Whereas the government in Sindh is designating pundits to solemnize and register marriages in that province, no such facility is available to Hindus living in Punjab. As a result, every single Hindu marriage conducted in Doda before 2021 has remained unregistered by the government.

This problem leads to another. Doda’s Hindu children do not get officially-verified birth certificates because their parents possess no government-sanctioned document to prove their marriage. When these unregistered children grow up, they face many other problems: how to be enrolled in a school or get a job (though some of them have clearly found some way to do that because they have not just gone to institutions of higher learning, they have also found government employment).

Ami Chand has recently pulled off a miracle of sorts in this regard: He has had his recently-married daughter’s marriage registered with the National Database and Registration Authority (Nadra) without having to produce her birth certificate and his own marriage certificate – the two important documents that he does not have. He did that in order to facilitate his masters’ degree holder daughter to develop her job application that requires her marriage certificate.

Initially, Ami Chand did not know where to get her marriage registered but his profession came in handy. Being the only veterinarian in his area, he provides treatment to the livestock of many influential people including politicians and bureaucrats. He knocked at the doors of some of these people for help and they readily obliged by ensuring that he had his daughter’s marriage registered with Nadra and obtained the required certificate.

Yet it is not a flawless document. It states that his daughter and her husband belong to Sikh religion. Ami Chand says he showed the Nadra officials a proof of their Hindu marriage – a document signed by a pundit and issued by a temple – but they did not bother to consider it. They instead noted down, on their own, the religion of both the bride and the groom as Sikhism.

He, however, is not much concerned about this error. “At least, my daughter will be able to apply for the job now,” he says. In any case, he argues, what difference does it make if you are a Hindu or a Sikh in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan? “She will remain and be treated like the member of a religious minority,” he says.

Those Doda residents who have joined the Muslim majority also complain that they are not often seen as equals. A newly converted tailor, who sports a long beard and a white shalwar kameez a la Muslim preachers, says his conversion has caused a clear rupture between him and his past but he is still unable to find a present that can own him without any reservations.

“Hindu offspring do not marry our children because they feel abandoned and betrayed by us and Muslims do not marry their children in our families because we were Hindus until recently,” he says.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 6th July 2021, on its old website.

Published on 16 Feb 2022