Mohan Lal Sawhney built a haveli, or a bungalow, in the city of Sargodha years before 1947. His three sons and one daughter all grew up there together even though they were born to two different mothers. His granddaughter Sonea Talreja remembers the summers of her youth when, in the 1970s and the 1980s, she would visit the haveli as well as her ancestral village of Salam located on an Islamabad-Lahore motorway exit near Sargodha.

“Every year my parents and all the children of the family would drive from Lahore to Sargodha to pay their respects at the 10th Muharram procession,” says Sonea Talreja who now lives in Dubai. The visit, according to her, was “a long family tradition”.

Mohan Lal, a pre-partition barrister, died in 1967 but familial bonds among his children and grandchildren remained strong even after his death. Only years later, a family dispute would arise with the death of his son, Madan Lal Sawhney, in 2006.

Madan Lal never married but he was close to his full sister Asha (who became Asha Talreja after her marriage) and her children. He played an “instrumental” role in convincing his sister and her husband to send their daughter, Sonea Talreja, to the United States for studies back in 1986. She describes him as “a traditional landed individual” who was very social and very well respected in his community.

Madan Lal was born to Mohan Lal’s second wife, Janki Devi and had inherited 50 percent of his father’s property through his mother who had died only a year before his own death. The other half of the property had already gone to the male progeny of Mohan Lal’s two sons from his first wife. They both had died before Madan Lal – one in 1974 and the other in 1980.

Following his death, Asha Talreja expected to inherit his property as his rightful and only heir but her half-nephews, Braspati Ram Sawhney and Iqbal Buland Sawhney, children of Mohan Lal’s sons from his first wife, also staked their claim on it. Their claim was based on Hindu religious principles as enunciated in the Hindu Law of Inheritance Act of 1929.

Religion versus constitution

Dinshaw Fardunji Mulla was a Parsi jurist in the British India. He was the author of several seminal texts on various aspects of Indian law of the time. Among many books he authored, his treatises on Muslim jurisprudence and Hindu law are still regarded as the bedrock of personal and family laws concerning Muslims and Hindus living in both India and Pakistan. The Hindu Law of Inheritance Act essentially stems from his interpretations of the Mitakshara school of Hindu jurisprudence.

After the independence in 1947, Pakistan inherited this act just as it inherited many other laws from the British India. One of its most fundamental provisions states that female heirs do not have a claim over any fraction of the inheritance of a deceased person in the presence of his/her male heirs.

It was only in February 2012 that Punjab Assembly amended the act to give the sister of a deceased person the right to inherit property left by him/her. She, however, was still ranked far lower in the succession order than male heirs.

So, when Asha Talreja and her half-nephews submitted their respective applications in a civil court in Sargodha for obtaining certificate of succession as the surviving heir of Madan Lal, the judge rejected her application and accepted those of Braspati Ram and Iqbal Buland. The judgment was based on a succession line derived from Hindu Law of Inheritance Act which puts the son of the deceased’s brother at number 10 and the full-blooded sister of the deceased at number 13.

Commenting on it, Iqbal Bulund “agrees” that his deceased uncle’s real sister should have been able to inherit his property but “it’s not that I have done [any discrimination against her]; it’s the law.” One must “follow the law of the land -- full stop,” he says.

Asha Talreja, on the other hand, was not happy with the judgment so she challenged it at the Lahore High Court. In her petition, she stated that her half-nephews were “illegally promoted” by the civil court “to serial No 10 of the table of heirs” though, according to her, this number “was meant for full brother’s son”.

When she died in 2011, her daughter, Sonea Talreja, took up the case.

Three years later, she filed a fresh petition at the Lahore High Court against the judgment made by the civil court in Sargodha in 2008. Unlike her mother, however, she did not base her petition on religious premises but, instead, contended that the Hindu customary laws and the Hindu Law of Inheritance Act of 1929 both were in violation of Pakistan’s constitution.

These laws, she pleaded in her petition, deprived women of inheritance merely due to their gender even when Article 25 of the constitution clearly states that “all citizens are equal before law and no person can be discriminated on the basis of sex”. She also cited Article 25 (3) of the constitution which allows the state to make “special provision for the protection of women and children”.

Also Read

Gender equality in inheritance: What men can have but women can't

Her petition further stated that though the constitution’s Article 20 provides that “every citizen shall have the right to profess, practice and propagate his religion”, this did not apply to “the matter of inheritance and other customary laws”.

Ali Sibtain Fazli, a senior lawyer based in Lahore who is representing Sonea Talreja at the high court, says the constitution does not allow any discrimination, including discrimination on the basis of sex. If there is a law that discriminates, he says, “then it is liable to be struck down”.

Pending justice

India introduced the Hindu Succession Act in 1956 which gives preference to full-blooded female descendants of a deceased person over his/her half-blooded male relatives. The Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, promulgated in India in 2005, similarly ensures that the inheritance of a deceased person is divided equally between his/her daughters and sons.

Back in Pakistan, ministry of human rights and minority affairs held a meeting in 2015 to discuss Sonea Talreja’s petition. Dr Ramesh Kumar Vankwani, the head of a Hindu civil society organization and also a ruling party legislator at that time, suggested that the involvement of legal experts belonging to Hindu community was essential in any discussion over changes in the Hindu inheritance law. Lawyer Fazli points out that the ministry then asked some Hindu legislators to consult Hindu pundits and other pertinent people so as to propose amendments to the law. Since then, no development has taken place as a follow up to those discussions.

“It has been six years since the high court invited comments and reports from the government of Punjab and the human rights and minority affairs ministry to review the inheritance law,” says Sonea Talreja. “It is very clearly a case of justice delayed, justice denied.”

Her lawyer has also written letters to the one-man minority rights commission set up by the federal government under a directive by the Supreme Court. But, as the copies of the communication between him and the commission show, her petition has not been even perused by the commission so far.

Suresh Jhammatmal, a lawyer based in Hyderabad, says one possible reason for a lack of progress on her petition is that there is no consensus among Hindu pundits in Pakistan on anything – including inheritance. He, however, points out that their opinion should not matter as far as legislation is concerned. “There is no role of pundits in legislation,” he says. The parliament has the power to pass any law while people are bound to comply with that law, he argues. As an example, he points to the Sindh Hindu Marriage Act of 2016 which was passed by Sindh Assembly without the involvement of pundits.

Sonea Talreja argues that even when consulting the pundits in her case is essential, there is no need to seek a fresh consensus among them. Top Hindu religious leaders and pundits in India have already given their opinion in the favor of providing equal inheritance to the descendants of a deceased, regardless of their gender, she points out. “It is, therefore, baffling that the relevant authorities in Pakistan are either disinterested or are shying away from replicating this to amend the old and discriminatory Hindu inheritance law,” she says.

Ruins of the past

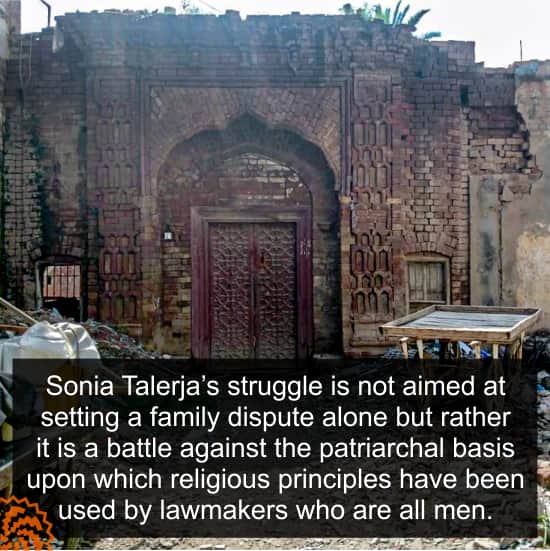

As Sonea Talreja awaits justice, the haveli built by her grandfather has been sold and demolished. “Its entire facade has now been turned into rooms and shops,” she says but does not know “what is left of the haveli anymore”.

She also accuses Iqbal Bulund and Braspati Ram of violating a Lahore High Court order which called for maintaining status quo on the bungalow’s condition. The order was issued on my request, she says, but they are selling and demolishing the building in violation of it.

Iqbal Buland, on the contrary, claims the status quo order was issued after the sale of the bungalow had already taken place. In any case, he says, “the ancestral property of the Sawhneys had to go to Sawhneys -- not to anyone else”.

Though the money involved in the dispute, according to Sonia Talerja, is “huge”, she insists that she has a problem less with money and more with the “betrayal” that her mother experienced at the hand of the children of her own siblings before she died. She also says that her struggle is not aimed at settling a family dispute alone but rather it is a battle against the patriarchal basis upon which religious principles have been used by lawmakers who were are all men.

And despite the very long delays in the final hearing of her petition, Sonea Talreja is not giving up. She has filed a written complaint with the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO), seeking a “speedy and fair judgment” in her case.

To her distress, however, no one from that office has responded to her so far.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 10th July 2021, on its old website.

Published on 16 Feb 2022