Kiran Masih, 15, was abducted on 8th March 2021, just as the international women’s day was being observed across the globe.

She was walking back home -- in northwestern Lahore’s Chung area -- from work when two masked men pulled her inside a car. Her mother, Hameeda Bibi, 60, who was accompanying her, tried to grab her back but one of the men punched Kiran on the head and threw her inside the car. The other beat Hameeda and pushed her away. She fell on the ground but quickly pick herself up and ran after the car that was speeding away.

“I shouted that my daughter was being taken away,” says Hameeda, still rattled after several weeks of Kiran’s abduction. Her cries made someone stop and take her to a local police station.

The police did not register her complaint. She kept explaining the circumstances of the abduction to them but they were of the opinion that Kiran had eloped with someone.

Kiran’s entire family -- parents, siblings and other close relatives – then started a sit-in protest in front of the police station. After an entire day passed to their protest, Hameeda suddenly stood up and announced that she was going to set herself on fire. The announcement jolted the police into action and they immediately registered a First Information Report (FIR) about Kiran’s abduction.

When, however, her family visited the police station next day, the police chief there told them that Kiran had left Christianity and converted to Islam. “He told us that we would receive documentary evidence of her conversion soon,” says Hameeda.

Three days after Kiran had gone missing, her parents received her conversion certificate and nikahnama (marriage deed) by post. The documents were issued by a Muslim seminary located near the shrine of Lahore’s patron saint, Data Gunj Bakhsh.

Hameeda fears the worst for Kiran. “Her abductors might abuse her physically and then sell her to some prostitution racket,” she says.

Her grief knows no bounds even though three months have passed since Kiran’s disappearance. She often roams around her neighborhood, searching for her daughter. Sometimes she goes to the spot where Kiran was abducted from and sits there for hours, waiting for her return.

Caught between religion and family

Charlotte Javed’s eyes drooped so often that she could not see anything distinctly. When she tried to keep them open, the walls around her would melt into a blurred whole. “They would inject something in my arm,” she says of her captors. “The injection would leave me with no energy to even get up or talk.”

Charlotte was abducted from a village in Faisalabad district on 27th January 2019 while she was visiting a relative’s house in another locality in the same area. Her relative was not at home, she says, so she went to his neighbor’s house to wait for his return. There, she alleges, a woman gave her tea laced with intoxicant which put her to sleep.

When she woke up, she found herself locked inside a room. Her captors give her food regularly but she would not even touch it. Worried that she might die of starvation, they forced her to eat. Mustering some courage, she asked them to send her back home. “We have purchased you in 50,000 rupees. You are our property now,” she recalls one of them telling her.

They were outraged. “If she has converted on her own, we will accept that but first the police need to find her and show us that she is safe,” says Kiran’s father, Bashir Masih.

Charlotte’s parents, meanwhile, were looking for her frenetically. They approached a police station for filing a case but were rebuffed. They then started a series of protests which compelled the police to register a case on 14th February 2019 against several people including the woman who had drugged Charlotte. She told the police that she had sold Charlotte to a rickshaw driver who in turn sold her to one Zafar Iqbal.

Iqbal was said to be detaining Charlotte at an unknown location.

When he came to know about the case registration, he presented Charlotte before a judge on 20th February 2019 and claimed that she had changed her religion from Christianity to Islam and was legally married to him. He also showed a nikahnama (marriage deed) to the judge.

It does not seem to have mattered to the judge that Charlotte was only 14 then so he allowed Iqbal to keep her with him.

“I did not want to say the words that make someone a Muslim but Iqbal told me that he will kill me so I kept repeating whatever he was telling me to say,” Charlotte says. “I was extremely scared.”

Her parents then moved the Lahore High Court for her recovery. In April 2019, the court decaled both her conversion and marriage as illegal which made Iqbal flee, leaving her in confinement.

She later managed to escape by getting her hands on a phone left behind by her captors. She called her parents and they took her back home.

Charlotte’s life, though, is still not back to what it used to be. “My brothers say it would have been better if I had stayed with Iqbal because they think that I have tainted the family’s honor,” she says.

They have stopped giving her money, leaving her care entirely to their ageing mother. Her relatives and neighbors also tell her family that they should not have brought her back. “I am often told that no one is going to marry Charlotte,” says her mother.

Daughters of a lesser god?

Many teenage Christian girls from central Punjab have endured similar ordeals in recent times. They were abducted, put in captivity and drugged or beaten unconscious to coerce them into leaving their religion and marrying their kidnappers.

The case of Maira Shehbaz, a teenager from Faisalabad, has attracted international media attention too. She was kidnapped in October 2019 but a Lahore High Court judge ruled in August 2020 that she had become Muslim and had married on her own.

A few days later, she fled from her abductor’s house located in Faisalabad. She later told the police that he filmed her while raping her and also threatened to kill her if she resisted his move to marry her.

After she was reunited with her family, her parents alleged that she was abducted in order to be sold off into prostitution.

Maira says she was mostly asleep during her confinement but “then suddenly a lot of voices would flood into my ears”. She could sometimes hear the gruff laughter of her kidnapper and his accomplices and their plans to sell her off.

She is still living in hiding because her abductor has threatened to kill her.

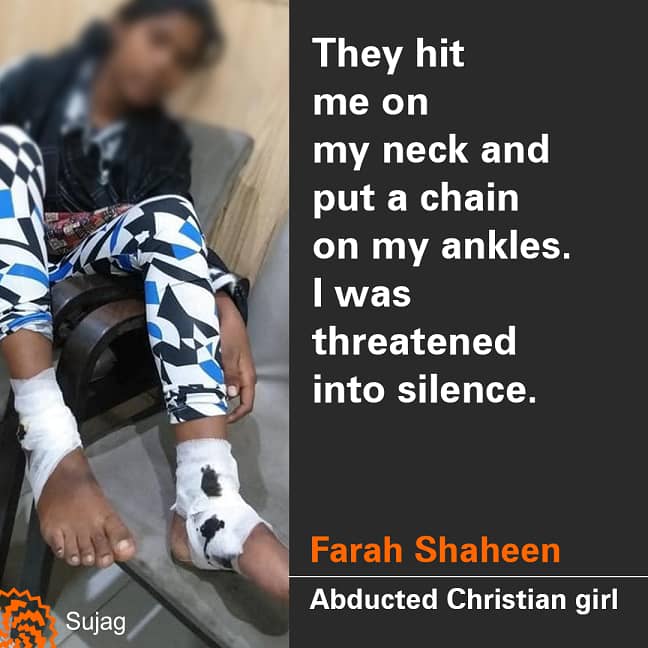

Farah Shaheen, also kidnapped from Faisalabad on 21st February 2021, similarly says that her kidnappers would threaten her into silence whenever she protested that she wanted to go back home. “They hit me on my neck and put a chain on my ankles,” she says.

Farah was barely 14 when she was abducted.

She was recovered from a landlord’s outhouse in Hafizabad district. During a court appearance in March this year, her ankles were badly wounded yet the judge hearing her case allowed her to go with her Muslim kidnapper because he claimed to be her husband.

Farah remains silent mostly and only smiles sheepishly when asked about anything. She also seems to be experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder. Her father says she gets scared easily and often jump out of her bed at night in dread.

The law’s flaws

Christian girls are routinely abducted from across Punjab, forcibly converted and married to their abductors. In some cases, they are also sold for sex work.

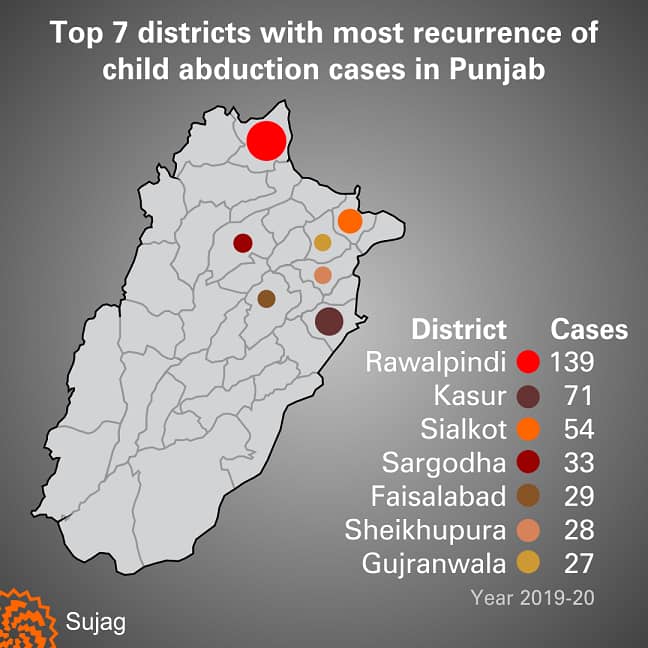

No consolidated data, however, is available to show their exact numbers. Some non-governmental organizations, such as SAHIL, do collect and publish data of children abducted from different parts of Pakistan but they do not segregate the victims on the basis of their religion.

Some human rights organizations claim that as many as 90 percent of the abducted non-Muslim children are girls who are then forced to convert to Islam.

No Pakistani law criminalizes these forced conversions. A bill passed by Sindh Assembly in November 2016 could not become a law because the provincial government withdrew it under pressure from Muslim religious groups.

The only legal recourse available to child brides from non-Muslim communities is an amendment that the National Assembly made in February 2017 in section 498 B of the Pakistan Penal Code. It states that anyone who enters into a forced marriage with a minor non-Muslim woman shall be liable to a maximum of 10 years and a minimum of five years in prison.

The problem is the police hardly ever apply this section in cases of forced conversion. They, instead, use section 365 B which deals merely with abduction.

Lala Robin Daniel, a Faisalabad-based Christian activist, says the judge did not bother to seek any proof of the marriage. “Instead, he asked the girl if she had married of her free will. She was so scared that she answered yes. This was enough for the judge to make the decision he made,” says Daniel.

A few weeks later, another court ruled that Farah was forcibly converted and married against her will.

She is back with her family now but is still living in hiding to ward off threats to her life. “Some people threaten us saying that she has converted back to Christianity from Islam and, therefore, is liable to be murdered,” says her father.

Also Read

A recipe for disaster: How Single National Curriculum will divide the country further along class lines

The application of this section often produces results that the Christian community resents deeply. “Once the abductors produce a conversion certificate, religious leaders step in, the police backs off and it is assumed that the victim has accepted Islam on her own,” says Sunil Malik, a Christian activist in Faisalabad. Ironically, he says, all this turns an abduction case into a case for preserving a religious conversion.

The commission’s failure

Shoaib Suddle, a former senior police official who now heads a one-man commission on minority rights, visited Lahore in early May 2021. Several human rights activists met him during his visit and pleaded him to recover Kiran Masih. He assured them that he would talk to the relevant authorities for her recovery but the police have still failed to find her.

The Suddle Commission was set up in 2018 by a Supreme Court bench headed by then Chief Justice of Pakistan, Justice Saqib Nisar. It is meant to oversee the implementation of a judgment that an earlier Chief Justice of Pakistan, Justice Tassaduq Hussain Jillani, made in 2014.

The judgment stated, among other things, that Article 20 of the Constitution of Pakistan gives every citizen the right to profess, practice and propagate his or her religion. It then explained: “This should not be seen as a right to encourage conversions but, more importantly, should be seen as a right against forced conversions or imposing beliefs on others because if all citizens have the right to propagate then no citizen has the right of forced conversion or imposing beliefs on others.”

These words still await implementation. “After 82 months and 23 Supreme Court hearings, only 24 percent of Jillani Judgement has been implemented,” says Asad Jamal, a lawyer and human rights activist based in Lahore. “This is a grave situation for religious minorities,” he says.

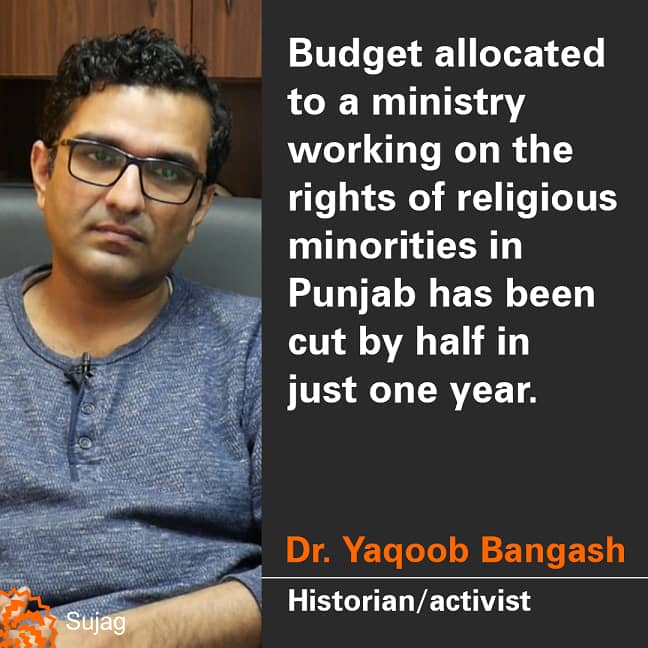

The delay in implementing the judgment, says Dr Yaqoob Bangash, a historian and human rights activist working in Lahore, is due to the fact that the state is not ready to do anything about the rights of non-Muslim Pakistanis. To make his point, he cites the example of budget allocated to a ministry working on the rights of religious minorities in Punjab. “This budget has been cut by half in just one year and is now less than that of a public university’s department,” he says.

“This clearly shows how serious the government is when it comes to the rights of religious minorities.”

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 10th June 2021, on its old website.

Published on 16 Feb 2022