Sarfraz Naeemi was the administrator of Jamia Naeemia, a madrassa in Garhi Shahu area of Lahore, when he was killed in a suicide bombing here on June 12th, 2009. Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, a religious militant group, accepted the responsibility for the attack. The reason for his assassination, they said, was that he had issued a fatwa declaring suicide bombings as un-Islamic.

With around 1,500 students, Jamia Naeemia is one of the oldest madrassas of Barelvi faction of Islam in Lahore. On a recent cloudy autumn afternoon, a young man, dressed in a black shalwar kameez and flanked by two excited men, enters its lofty iron gate. Introducing himself as a ‘Qadiani’, he tells the bearded receptionist that he has come here to convert to Islam.

The word ‘Qadiani’ is a derogatory attribution used for the followers of Ahmadi faith. The person wanting to leave this faith belongs to Narowal, a city in the northeast of Lahore. His conversation with the receptionist and others at the madrassa shows that his decision to convert is voluntary. He, however, admits that his Muslim friends and a preacher in Narowal have “guided” him to reach this decision.

The staffers at Jamia Naeemia tell him that he needs to provide them some documents in order to obtain a conversion certificate. These include his photograph, a copy of his identity card and an affidavit on a stamp paper signed by two witnesses and clearly mentioning that he is abandoning his religion and converting to Islam by his own will.

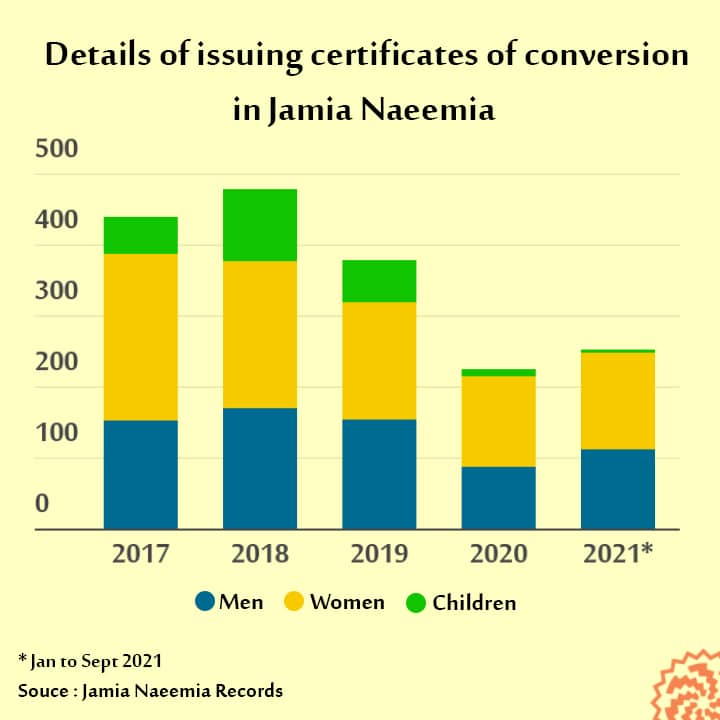

Raghib Naeemi, who has replaced his slain father, Sarfraz Naeemi, as the administrator of Jamia Naeemia, says his madrassa maintains a record of all the non-Muslims who have converted here since 1970. On average, he says, 300 non-Muslims convert to Islam every year at this madrassa. An extreme caution is observed to ensure that they are not converting under any duress, he adds.

Certifying forced conversions

Over the last few weeks, Sujag has collected 27 conversion certificates issued by various madrassas, religious-political groups, religious associations and even non-government organisations. The madrassas include Darul Huffaz Faisalabad, Jamia Rizvia Mazhar-e-Islam Faisalabad, Jamia Islamia Karachi, Jamia Darul Uloom Karimiyah Sindh and Darul Ifta Ahl-e-Sunnat Punjab; among the political groups are Pakistan Sunni Tehrik and Anjuman-e-Ghulaman-e-Mustafa; and social welfare organisations are Huqooq-un-Naas Welfare Foundation and Bazm-e-Ifadaat-e-Khaleel Pakistan.

The contents of these certificates are also not uniform.

Raghib Naeemi admits that most of them have flaws. Some of them, for instance, do not include the identity card numbers or the photos of the converts. But these flaws notwithstanding, he says, “any [Muslim] can issue a conversion certificate” because, as he explains, “Islamic Shariah makes it obligatory upon every Muslim to help out a person who intends to convert to Islam”.

Sunil Malik, a Christian social worker from Faisalabad, does not see this as a helpful situation for the non-Muslims living in Pakistan. He says it is unfortunate that there is no law in Pakistan that stipulates as to who can issue a conversion certificate, what kind of evidence is required for a conversion to be authentic and what should be written in a conversion certificate.

Sujag, too, has at least three certificates that highlight how the absence of a uniform national standard for their issuing has created a plethora of problems for non-Muslim Pakistanis. Despite the fact that the subordinate judiciary had accepted these three certificates as authentic, the superior courts annulled them all and declared that the people converted through them were threatened and coerced to abandon their religions.

Sumaira Malik, a lawyer based in Lahore, has represented one such person in a court of law. She says judges in lower courts mostly have little knowledge about the social and legal complications related to forced conversions. To address this issue, she is currently conducting a training program for lawyers and session judges, with a special focus on how a conversion certificate should not be accepted as authentic unless it is properly scrutinised and verified.

Sujag’s research also reveals that it was on the basis of such suspicious certificates that lower courts and police handed over at least four minor Christian girls from Punjab — Farah Shaheen, Charlotte Javed, Kiran Masih and Maira Shahbaz — to those who had forcibly converted them to Islam. The relatives of the girls later succeeded in proving before higher courts that they were made to accept Islam against their will. Consequently, they were reunited with their families.

The ordeal of 25-year-old Shama Bibi, a resident of Gujranwala, also underscores how deciding such cases on the basis of a conversion certificate alone can lead to the trampling of some fundamental human rights. She was working at a private bank last summer when one day Muhammad Imran Virk approached her for obtaining information about insurance. He told her that his wife, Rukhsana, was also interested in buying an insurance policy. He, therefore, suggested that Shama accompany him to his house so that he and his wife could sign the relevant documents there together. Since Imran was married and had two children, she agreed to go with him.

But, she says, Virk took her to some fields instead of taking her to his house. He raped her there while an accomplice of his videotaped the whole incident. Over the next several weeks, he continued to blackmail and rape her on the basis of that video. As a result, she became pregnant.

Later, in October 2020, Virk abducted Shama from her house and shifted her to his own house where she was detained in a room. In the meanwhile, she says, he managed to arrange a fake conversion certificate and a marriage deed (though she had neither embraced Islam nor tied the nuptial knot with him).

After Shama had spent three days in captivity, Virk’s wife, Rukhsana, helped her escape. So, she ran away and reached her brother-in-law’s house. But on the night between October 16th and 17th, Virk came there armed and accompanied by his friends. After badly beating Shama, he dragged her by her hair and took her again to his house. The torture she suffered in the process fractured her ankle (a fact later confirmed by a medico-legal report issued by a government hospital on October 31st, 2020).

When this case was first heard at a local court, the judge accepted the conversion certificate and the marriage deed as authentic and declared Virk and Shama as husband and wife. But Shama’s family immediately challenged that decision before the Lahore High Court where she stated in a written statement on October 29th that “I have Imran’s child in my womb but neither am I his wife nor am I a Muslim”.

Raghib Naeemi, on the other hand, claims that most such cases “are not based on reality”. He instead says most of these Christian girls ran away from their homes to marry Muslim men but their families filed cases of forced conversions to avoid the social stigma attached to their elopement.

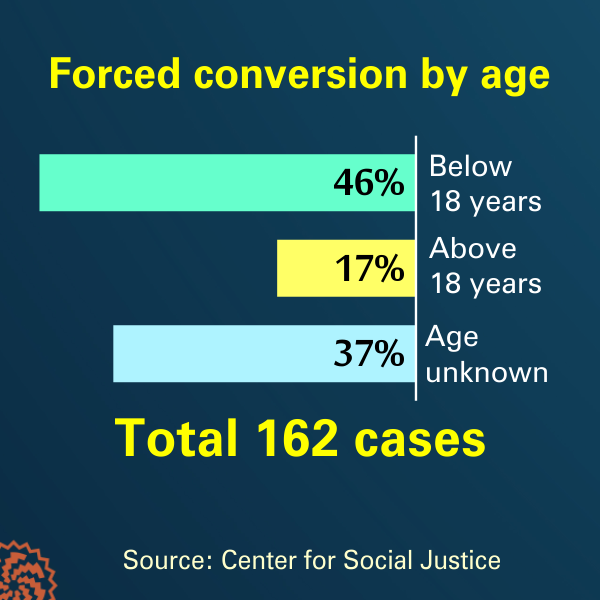

Human rights activists, however, have come across a number of cases of conversion of minor girls who were not mature enough to weigh the pros and cons of their own decisions.

Vulnerable religious minorities

In March 2019, the issue of conversion of two Hindu sisters, Reena and Raveena, surfaced in Ghotki district of Sindh. They had purportedly married two Muslim men by their own choice. It was in the wake of this incident that a committee of the Upper House of the Parliament, Senate, was formed to delve into such conversion cases in Sindh.

The committee later constituted a sub-committee and gave it the task of drafting a law to curb forced conversions. The sub-committee included Sikandar Mendhro of Pakistan Peoples Party, Rana Maqbool of Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz, Lal Chand Malhi of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf and Barrister Muhammad Ali Saif of Muttahida Qaumi Movement.

It subsequently drafted a law which

• Determined a minimum age for those converting to a religion voluntarily;

• Proposed to confer the powers of issuing a certificate of conversion only on district and sessions judges;

• Gave 90 days to an intending convert to deliberate upon his/her decision to convert after submitting his/her conversion application with a judge;

• Deemed a marriage forced if it was carried out without the consent and free will of the bride and the groom;

• Proposed an imprisonment ranging from five to 10 years and a fine of 100,000 rupees to 200,000 rupees for those found involved in the forced conversion of a child.

Federal Minister for Religious Affairs, Noorul Haq Qadri, however, took strong exception to this draft when it was presented before Senate for a debate. In August this year, he convened a Muslims-only meeting of religious scholars in Islamabad. According to daily Dawn, the participants of this meeting rejected the proposed law unanimously.

Raghib Naeemi also opposes the draft. He believes it will make it altogether impossible for non-Muslims to convert to Islam. He also opposes the provision of giving 90 days to an intending convert to reconsider his/her decision. “The converts generally face a great deal of pressure from their families. During this period, this pressure may get so intense that they might change their decision to convert,” he says.

The Islamic Ideological Council (IIC) has also held a meeting in Sindh where the conversion of Hindu girls to Islam is a common phenomenon. The meeting was allegedly chaired by a political and religious figure, Mian Abdul Haq alias Mian Mitha, who is widely accused by human rights activists of being involved in abducting young Hindu girls and forcibly converting them to Islam.

Mitha declared the proposed law being in violation of Islamic injunctions and raised 42 objections to it. One of his main objections pertained to a proposed legal action against those involved in abetting a forced conversion.

For Peter Jacob, a Lahore-based human rights activist, all these consultations on the proposed law were flawed. If the government wanted a balanced discussion on the draft, he says, non-Muslim stakeholders should also have been invited to take part in it.

In a recent Senate session, five non-Muslim senators from different parties have also opposed the rejection of the draft. “If Muslim senators consider this draft against Sharia, they should have amended it to make it in accordance with Islam. It should not be rejected outright because doing so is akin to pushing religious minorities against the wall,” they argued.

Also read

What’s in a name? Many Christians find their religious identities changed in NADRA records

When these minority parliamentarians requested the Senate Chairman to have a vote on the draft, he refused to do so and declared such voting against “public interest.” He then consigned the draft to the legislative dustbin by saying that there is no need to discuss it further.”

Pushpa Kumari, a human rights activist from Sindh, expresses grave concern over this whole process. It seems the parliamentarians are “scared of religious extremists,” she says.

Senator Lal Chand Malhi – who too comes from Sindh -- also has problems with how the views of the minorities have not been heard during the rejection of the draft. He says that, as a Hindu, he feels that there is no justification for him to remain a member of the Parliament if he “cannot so much as raise his voice for his community”.

Published on 19 Nov 2021