Ahmed* always wanted to realize his father’s dream of seeing him become a doctor.

The biggest upset that he faced in this pursuit was his failure to qualify for an admission in a public sector medical college in 2019. His father assured him that he could finance his education in a private college but Ahmed decided to make a second attempt at scoring better in the Medical and Dental College Admission Test (MDCAT) in 2020.

This, too, did not go well.

Several quick changes in the test’s syllabus only weeks before it was held left his preparations in tatters and he, again, could not secure enough marks to get into a public sector medical college. Now he has only one option left: to enter a private medical college.

This option, however, has become more costly than it was in 2019-20 and he is unsure if he has all the money it requires. “My biggest regret is not getting admission in a private medical college last year,” he says.

Ahmed’s father is a real estate agent in Swat, the tourist valley in northern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. His income has dropped in 2020 because the selling and buying of property has experienced a slowdown in his region due to coronavirus. He, therefore, can no longer afford the cost of sending his son to a private college without securing additional financial resources urgently.

To do that, he has decided to sell his share in his ancestral land. “The proceeds of the sale will hardly be enough to pay for the first two years of my education,” says Ahmed. To defer the cost of the remaining three year, his father will have to sell his car and then some other valuables, though the money thus earned will not be sufficient. “My father is also planning to take a loan from his brothers,” Ahmed adds.

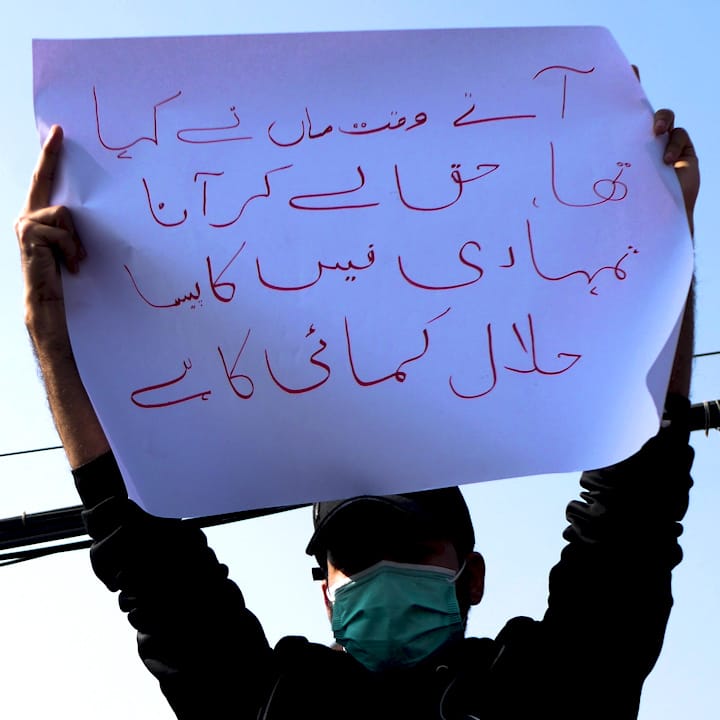

He never wanted any of this to happen because he knows that an expensive private education for him will have serious financial implications for his whole family. “If my parents invest all their resources in my education, I will be robbing my four younger siblings of their rights,” he says.

Sadia Zaid’s worries are different only in their details.

A resident of Rawalpindi, she has been working to secure an admission in a public sector medical college while her mother, diagnosed with tongue cancer, fought for her life. She not only had to prepare for MDCAT in 2019 but also had to look after her mother and two younger siblings. Consequently, she did not score well enough in the test to qualify for an admission in a public sector medical college.

In 2020, she decided to reappear in the test and started preparing for it very early but she suffered a massive setback when her mother died on March 7, 2020. Emotionally devastated, she could not do well again in MDCAT 2020 and did not qualify to get into a public sector medical college.

Sadia’s father has married another woman and has five other children to take care of besides the three from his first wife. With no other source to fund her education in a private college, Sadia will have to sell her mother’s jewelry and other family heirlooms to put together the required amount of money. “It breaks my heart that I could not live up to my potential in the test, and have to resort to such desperate measures,” she says.

Areeb** has similar problems to contend with.

He passed his intermediate exam from the Government College University, Lahore. MDCAT 2020 was his second attempt to get into a public sector medical college but, having failed that, he is now seeking admission in a private institution.

Much to his chagrin, however, the fee being charged by private colleges is way beyond what his family can afford. His father is a retired military official now working in the security section of a bank in Lahore. He keeps going through his bank accounts, prize bonds and other savings as if he wants all his assets to double immediately so that he can send Areeb to college.

“My father is paying the first year’s fee through his savings put together over a very long time. Next he will be selling a plot that he had purchased a few years ago,” says Areeb. This money will help him pay for the first three years of college but he and his father are still not sure whether – and wherefrom – they will arrange his educational expenses for the remaining two years.

“It pains me greatly that my father has to give away his life savings and assets he has acquired after years of hard work just so the private education mafia can rob us dry,” says Areeb. “It seems that we are not dealing with the Pakistan Medical Commission but with the Private Medical Commission.”

Show me the money

A major part of the changes introduced by the Pakistan Medical Council (PMC), the newly set up regulatory body for medical education and practice, is the freedom given to private medical institutions to determine their own fee structures. Section 24 of the PMC Act, passed by a joint sitting on the parliament in the second half of 2020, gives a breakdown of the fees that a private institution can charge. It not just includes an annual tuition fee but also “non-refundable admission fee, hostel charges, transport charges and all other charges”. The cumulative fee now being charged by private medical colleges has gone beyond expectations of students. Following is a comparative analysis of the fee being charged for the course of the five-year program of medical education in some renowned private institutions of Pakistan.

These statistics indicate that there is no set criterion for the fee increases. For instance, the students being enrolled at Jinnah Medical and Dental College this year will have to pay 842,300 rupees more than what the students enrolled last year have to pay during the course of five years of their medical education. On the other hand, Combined Military Hospital (CMH), Lahore has been allowed to increase its fee from 4,527,912 rupees to 7,979,620 rupees – showing a massive increase of 3,451,708 rupees.

The other problem that students like Ahmed, Sadia and Areeb are facing is that the quality of education in private sector is strongly linked to the amount of fees being charged. Educational institutions offering higher standards are very costly whereas the ones with comparatively low fees offer poor quality education.

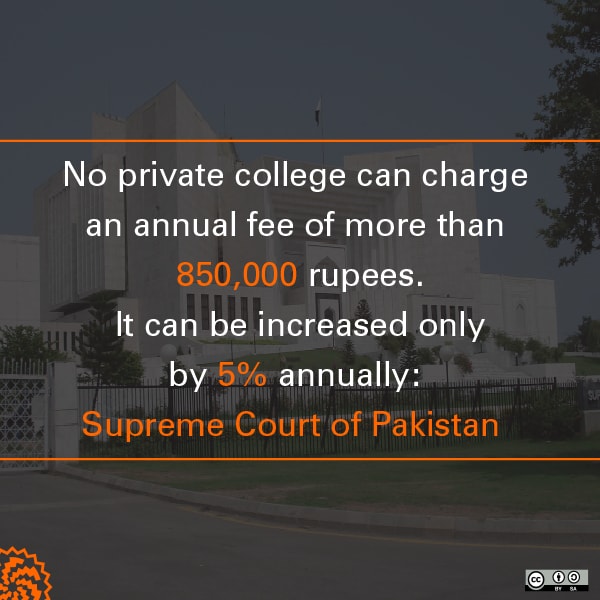

All this is in sharp contrast with a 2018 verdict by the then Chief Justice of Pakistan, Mian Saqib Nisar, which stated that no private college could charge an annual fee of more than 850,000 rupees which can be increased only by five percent in every subsequent year. That cap, for all intents and purposes, is gone now.

Commenting on this situation, Dr Zulfiqar Bhutta, the last president of PMC’s predecessor regulator, Pakistan Medical and Dental Council, says the efforts made by the Supreme Court to rein in private medical colleges have been derailed. “Medical education is being made increasingly unaffordable, especially for the middle-class families,” he says in an interview with Sujag.

PMC’s President Dr Arshad Taqi, on the other hand, does not consider it a problem at all. “If the parents feel that the cost of private colleges is too high, they should consider other more affordable fields of study for their children,” he says. According to him, “private institutions charge extra because they provide their students with more facilities than public sector institutions do”.

In any case, he says, “private medical institutions have been instructed to make their fee structures public before admissions”. This, he believes, will give “students and their families’ sufficient time to decide whether or not they can afford to pay these fees.”

* The name has been changed to protect identity

** The second name is not being given on request

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 14 Jan 2021, on its old website.

Published on 8 Jun 2022