Malik Waheed Ahmed runs a shop that is so small that only one person can sit in it at a time. He sells tablecloths and handkerchiefs but his business is not doing well because his shop is located in an area -- Korian Pull in Faisalabad -- that does not attract a large number of shoppers. Ahmad says he earns as little as 1000 rupees a day.

Four years ago, he was earning hundreds of thousands of rupees every month. He owned a factory that made cloth from cotton yarn on 24 power looms. He was also running another similar factory on lease.

In 2018, however, he not only had to close down both his factories but also sell his power looms at a very cheap price. He says he had bought each loom for 800,000 rupees in 2016 but he got only half that price two years later. Since he had taken a loan to set up and run his factories, he had to sell his house to cover the deficit in the buying and selling prices of the looms. Since then he has had no choice but to run a shop to earn a living.

Hundreds of industrialists like Ahmed have fallen victim to a similar recession in Faisalabad in recent times. About 35,000 power looms have been sold for virtually nothing in just one locality of the city, Ghulam Muhammad Abad, he says.

A few years ago, power looms could be heard operating throughout the day in many parts of Faisalabad. Local people had become accustomed to hearing their incessant clickety-clack coming from thousands of buildings with thin walls and low ceilings. Craftsmen could be seen moving inside these buildings, working on the looms. In 2017-18, the number of power looms in Faisalabad was anywhere between 250,000 to 275,000, says Ahmad. There were about 40,000 power looms in Ghulam Muhammad Abad alone.

But now the sound of power looms is audible only sporadically. Most of the factories in Korian -- where 30,000 or so power looms were working a few years ago -- have now been locked down or their owners have sold their looms and started other businesses. Consequently, Faisalabad's economic woes have intensified and power loom workers have to do all kinds of manual jobs to survive.

Munir Ahmad is one of them.

On a hot April afternoon, he is loading cotton bales on a handcart in Faisalabad’s Sootar Mandi (or yarn market) to deliver them to various shops. His son, Adil, was an eighth-grader at a local private school until four months ago but now he also helps his father transport the bales. The two pull their cart through crowded streets of Sootar Mandi all day and barely make enough money to put a day’s food on the table.

If he makes 20 rounds of his cart a day, says Munir, he can earn up to 600 rupees. With that money, however, he cannot meet all the needs of his three children and a wife.

Two years ago, he was working as a shift in-charge at a power loom factory in Ghulam Muhammad Abad and was living a relatively prosperous life. His salary was 35,000 rupee a month and the factory owner would give him free clothes for his entire family both on Eid and Shab-e-Baraat.

The origin of the crisis

The supply of cotton yarn required for power looms decreased drastically in 2018 so Waheed Ramay had to close down his factory with 38 power looms in Faisalabad’s Qadirabad area. The factory has now been replaced by a plant nursery.

Ramay, who is also the president of Power Looms Owners’ Association, believes the ongoing decrease in local cotton production has been a main reason for the decline of many cotton-related industries in Pakistan – including the power loom sector.

Official figures confirm that cotton production in Pakistan has been steadily declining over the last many years. According to a State Bank of Pakistan report published in 2020, cotton production decreased by 4.2 per cent last year as compared to 2019. The government’s estimates say this year’s production will be even lower and will be reduced to just five million bales.

A report released in December 2020 by the US Department, on the contrary, says that Pakistan’s expected cotton production in 2020-21 will not be more than 4.7 million bales. This is 24 per cent less than the cotton produced last year. The main reason for this decline is that the area under cotton cultivation has decreased by 10 per cent this year as compared to 2019-20.

If the current cotton production is compared with 13.6 million bales of cotton produced in Pakistan in 2014, one can realize that the production of this crop has declined by about 60 per cent in the last seven years. Pakistan, therefore, has to import millions of bales of cotton every year to meet its local demand. This year, too, about 4.9 million bales will be imported.

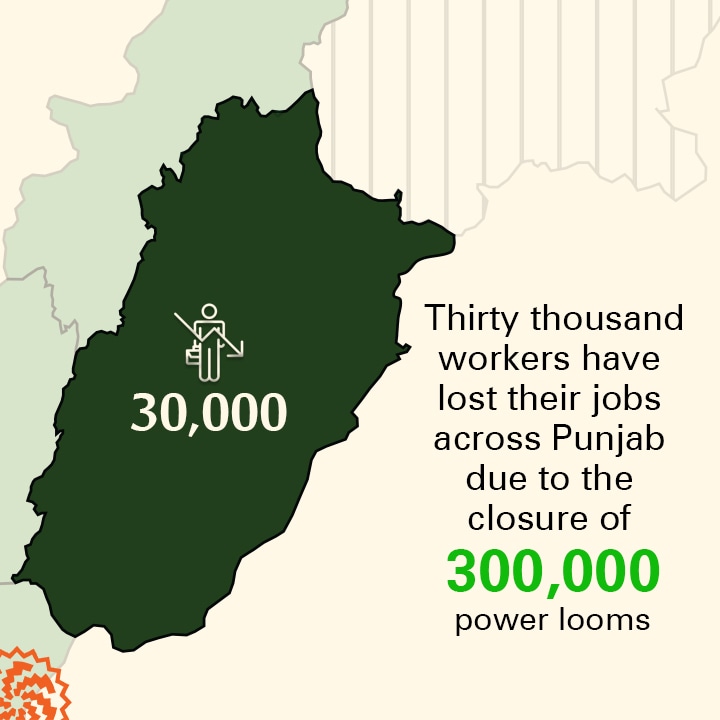

Ramay says cotton was once Pakistan’s white gold but the promotion of sugarcane as an alternative crop, incentives given to big investors for sugar produced from sugarcane, the cost of electricity required to run small textile factories, the easy availability of smuggled fabrics and the decline in textile exports to Afghanistan have destroyed the cotton crop and many industries related to it. According to him, 300,000 power looms have been shut down and 30,000 workers have lost their jobs across Punjab in the recent past.

Mumtaz Ahmed, a spokesman for All Pakistan Yarn Traders Association, also blames the decline in the country’s cotton production and the textile industry’s reliance on imported cotton and imported cotton yarn as the root cause of problems in the power loom sector. As a result of this dependence, he says, big investors have acquired the ability to change the prices of cotton and yarn whenever they want. This has severely affected small traders and the owners of power looms, he says.

Also Read

Fighting climate change with nuclear technology: cotton seeds that resist changing weather patterns

He explains his point of view by saying that big investors import cotton and yarn from other countries in such a way that they get control over the demand and supply mechanisms of the entire local market. Consequently, he says, the price of a sack of yarn increases by up to ten thousand rupees with a week. “With such unexpected rises in prices, big capitalists have become billionaires but medium and small businessmen have become poor.”

Whatever goes up comes down

The upswing in the power loom sector came about ten years ago when large textile factories began replacing their power looms with air jet looms. At that time, small investors bought the abandoned power looms and started using them in cloth manufacturing at a smaller scale.

In just a few years, though, the tax system changed in a way that the profit margins of these looms waned. Since these looms are not registered with the government tax machinery so they have to pay heavy taxes on their electricity bills while large factories are exempt from these taxes because they are registered with the tax machinery.

Similarly, according to Ramay, the owners of power looms have to pay 9 US cents as sales tax to import one sack of cotton but this tax is not being collected from the big manufacturers.

In other words, an improvement in local cotton production alone will not make these looms profitable again.

The ever worsening plight of this sector, indeed, is evident from a recent report published by the All Pakistan Business Association, a non-governmental organization of business persons and organizations, which shows that the number of people working on power looms is declining every day. Those who are still engaged in this sector either do not want to sell their power looms at throwaway prices or have their own family members working in their factories, the report states.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 12 May 2021, on its old website.

Published on 27 May 2022