Water in the wells of Gorano village has turned black. “Water gives life, but it has become a threat to our very survival,” laments Lachhman, 42, a local resident, pointing to one such well.

With a population of over 2,000 people, Gorano is located 30 kilometres southwest of Islamkot, a town in Sindh’s eastern district of Tharparkar. Just one kilometre away from the village, a huge reservoir has been built to store wastewater from coalmining. It is spread over many hundred acres.

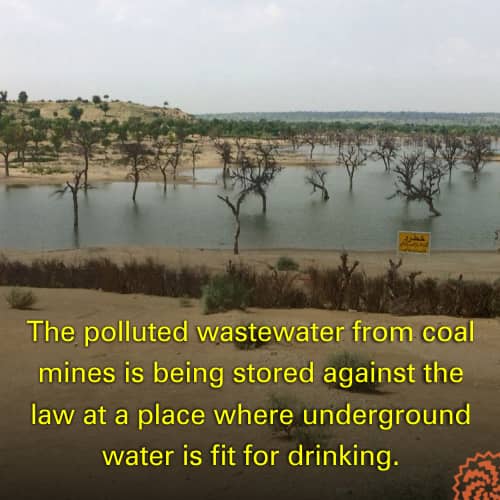

Its stench can be felt even from several hundred metres away. A large number of trees inside it can also be seen from afar -- their branches withered and trunks turned black.

The reservoir, though, is fenced by a barbed wire and bushes which make its large portions invisible. Only at some places its water is so close to the fence that its black colour can easily be seen.

The wastewater is piped to it from an area designated as Thar Coal Field Block-II in the government documents. A firm called Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company -- a joint venture of Sindh government and a private company, Engro Energy Limited -- extracts coal from this field to generate electricity.

When coalmining started in Thar Coal Field Block-II in early 2016, the work on the reservoir in Gorano also began even though coalmines are located as far as 47 kilometres to the north of the village. Mohsin Babbar, spokesman of Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company, says Gorano was chosen for building the reservoir because its geographical characteristics make it highly suitable for storing a large quantity of wastewater.

Local residents, though, object to this. They say the reservoir should have been built next to the coalmines, not close to a human settlement. They also contend that the reservoir should have been built in an area where groundwater is brackish and unusable rather than building it in Gorano where (before 2016), groundwater was sweet and fit for human consumption.

That is why, they argue, building the reservoir in their village contravenes Section 11 (1) of the Sindh Environmental Protection Act, 2014, which clearly states: “…no person shall discharge or emit or allow the discharge or emission of any effluent, waste, pollutant, noise or any other matter that may cause or is likely to cause pollution or adverse environmental effects...”

Similarly, the locals claim the construction of the reservoir was started without taking them into confidence. This was done despite the fact that its site was a source of livelihood for hundreds of people in Gorano and its adjoining villages, they say.

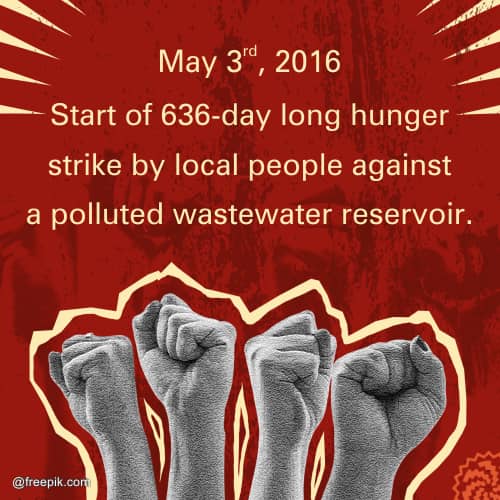

Consequently, the residents of these villages launched a series of protests against the reservoir’s construction. At the outset of this agitation, dozens of women, men and children went on a hunger strike in front of Islamkot Press Club on May 3rd, 2016. Their strike continued for the next 636 days.

Lachhman also participated in these protests. Initially, he says, the villagers demanded that the site of the reservoir be shifted away from human settlements, the locals be adequately compensated for the land acquire for it, jobs be provided to those local youth in coalmines and power plants who have lost their livelihood because of its construction.

Some Gorano residents, meanwhile, moved the Sindh High Court (SHC) on June 23rd, 2016 through a local lawyer, Leela Ram. They prayed to the court to order the shifting of the reservoir to some other place because, they contended, it will have hazardous effects on their social and economic life as well as on the environment of their area.

But, as Lachhman says, SHC did not take any immediate action on their request. On the contrary, he says, “the hearing of the case is still going on more than five years after it was filed”.

Some of the people affected by the reservoir also started a protest sit-in at Karachi Press Club on December 22nd, 2016. It continued for 22 days -- all in vain though. Neither did Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company ever bother to pay any heed to their demands nor did Sindh government and local elected representatives make any serious efforts to address their grievances.

On the other hand, Sindh government gave its approval in the third week of October 2021 for mining activities in Thar Coal Field Block-III as well. This has triggered fears among the locals that “the reservoir could be expanded to as many as 4,000 acres”.

Babbar, however, says these reservations are unfounded because the entire area covered by the reservoir does not exceed 1,500 acres whereas only 500 acres of them are being used presently to store wastewater.

Testing times

Attaullah Rind is a geologist in Tharparkar. He is affiliated with Thar Technical Forum, a local non-government organization that compiled a report recently on wastewater from Thar Coal Field Block-II.

The report, Rind says, concludes categorically that “the wastewater reservoir in Gorano has made underground water of 12 villages adjacent to it not just undrinkable but also unsuitable for irrigation”.

According to him, laboratory tests of the reservoir’s water reveal that it contains 7,000 to 8,000 milligrams of total dissolved solids (TDS) in each litre. The standard set by the World Health Organization for water most suitable for drinking, on the contrary, is only 300 milligram per litre. Consequently, says Rind, the reservoir has turned underground drinking water extremely contaminated in Suleman Hajjam, Shiv Jo Tar, Gorano, Nebo Ji Dhani and Allhay Ji Dhani villages, posing health hazards not only to human beings but also to livestock.

These findings, however alarming they might be, are no revelations for the residents of Gorano. Water in their local wells, they say, has turned into a black and stinky fluid since long. This forces them to walk three to four kilometre each day to fetch drinking water from an adjacent village, Kaattan.

They say the quality of underground water in their area has gone so bad that even a reserve osmosis (RO) plant installed by Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company in Gorano is producing contaminated water. The consumption of this water is causing arthritis and other bodily pains among local residents, they complain.

“The reservoir has also become a breeding ground for mosquitoes, pests and stinking toxins which are causing a rapid rise in the incidents of malaria, cholera and respiratory diseases in the villages,” says Lachhman.

A report released in May last year by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Water (CREA), a European research institute, backs such complaints. It states that coalmining and coal-fired power generation in Tharparkar are increasing the cases of asthma, malaria, diarrhoea, premature births and disability among the local population.

Also Read

Water, water everywhere nor a drop to drink: Water reservoirs built for power plants imperil a thirsty Tharparkar village

Lachhman and his fellow villagers argue that the problems they are facing could have been avoided by simply building the reservoir elsewhere. They also claim that its construction, in fact, is a violation of Sindh government’s own rules and regulations which stipulate that such reservoirs should be built at a distance of at least five kilometres from human settlements.

Similarly, they see the reservoir as a contravention of the license issued by the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (Nepra) to Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company for power generation. The terms and conditions of this license, they say, make it binding upon the company to not only put in place a proper mechanism for the reduction of hazardous emissions “but also evolve an environment-friendly policy for recycling wastewater” produced during coalmining and power generation.

The polluted wastewater being dumped in Gorano, however, offers ample proof that the company has failed to come up with any such policy.

Babbar, nevertheless, does not agree with the residents of Gorana. “There is no proof of the polluted groundwater around the reservoir,” he says. To back his claim, he cites a chemical analysis report conducted by his company and says this analysis does not throw up any evidence for the presence of medically harmful particles in water drawn from the wells near the reservoir.

Published on 30 Oct 2021