Bushra Shahzad felt a lump in her breast in 2018. She did not know what it meant so she told her husband, Shazad Malik, about it. He suggested her to get it checked.

To do that, she visited a homeopath in her neighborhood of Saddar in Lahore. He examined her, prescribed some homeopathic medicine and told her the lump consisted of concentrated fats and, therefore, was nothing to worry about.

She took the medicine for a year but the lump did not go away so she consulted the homeopath again. He reassured her that it posed no risk to her health.

Not long afterwards, she felt the lump was getting harder and more painful. She also observed black spots around it. She was horrified. When she told her husband about it, he dismissed it, saying: “It is probably an infection”.

She ended up consulting another homeopath who told her the same thing: that the lump was caused by concentrated fats. He, however, also suggested that she should undergo mammography – an x-ray of her breasts.

That test somehow kept getting delayed. She did not want to go alone to get it done but her journalist husband could not find time to accompany her. She finally told her only son, 18-year-old Ali Malik, about her condition. He immediately drove her to Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, a government-run healthcare facility in central Lahore.

Doctors at the hospital informed her that she was suffering from second stage breast cancer which could be cured with treatment. They told her to give up homeopathic medicines immediately and, instead, get chemotherapy, a process which uses allopathic medicine to kill cancer cells.

Bushra did not heed their advice and continued to take homeopathic medicine. “My mother refused to undergo chemotherapy because she had heard from someone that it is a very painful process,” says Ali.

Within a few weeks, her breast lump enlarged. Ali recalls his mother saying, “It feels like a small fist”. The doctors suggested a biopsy – a test in which a tissue from the lump was to be taken out and examined closely. The test revealed that cancer had started spreading in her body. Urgent chemotherapy was the only way to stop it.

Bushra still refused the treatment even though her health was deteriorating rapidly. She was now a stage four breast cancer patient – with no chances of survival.

Even at this stage, she was taking homeopathic medicine.

When her food intake dropped drastically and her speech and breathing became extremely labored, her family took her to a hospital to take out the fluid that had accumulated in her lungs. The procedure left her at the door of death. ‘She was no longer responding to any medicine and was slipping away from life at a rapid pace,” says Ali.

Bushra died on 19th May 2020 at the age of 54.

Another resident of Lahore, Nabila Masood, died in almost the same way in September 2018. She was 51 years old then.

Around nine month before her death, she started having a burning sensation in her right breast. She did not take it seriously. Her mother was on her deathbed and she was so occupied with her care and other household chores – as well as by her job as a private school teacher -- that she found no time for her own medical examination.

And then one day she noticed that her breast was deformed, heavy and hard. Her mother, too, had suffered breast cancer years ago so she knew that these symptoms could be dangerous.

Shaken, she rushed to the Cancer Care Hospital, a private healthcare facility set up by a renowned oncologist, Dr Shaharyar, on Lahore’s Raiwind Road. Mammography at the hospital revealed that she had stage three breast cancer which had entered her liver too.

After this diagnosis, her son, who works as a dentist at a trust-run hospital in Lahore, started seeking appointments for her treatment. He also approached Lahore’s Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital, set up by Prime Minister Imran Khan in the memory of his mother who had died of cancer.

Since Nabila’s husband was living a retired life and her children had just started their professional careers so her family could not afford to have her treated as a ‘private’ patient. They, instead, requested the hospital to take her in as a ‘free’ patient. Consequently, it took the hospital a whole month to even examine her. Her next examination, too, was scheduled three months later.

When, in the interregnum, her pain became too much for her to bear, her family rushed her to Jinnah Hospital, a large public sector healthcare institution in Lahore. Realizing that cancer treatment facilities there were just basic, they hurriedly moved her to a private hospital – which refused to admit her.

The hospital’s administration said her condition was too serious to improve with hospitalization. “No one wants to take the responsibility of providing care to a dying person,” complains Namra Aleem, the older of Nabila’s two daughters, who worked at a private firm in Karachi before quitting her job and relocating to Lahore to take care of her mother.

After several unsuccessful visits to various doctors and hospitals, Nabila ended up in Ittefaq Hospital, a trust-run institution in Lahore. A cancer specialist there examined her medical records and informed her that she did not have more than six months to live.

“By the end of it all, I would pray for my mother’s death because it was too difficult to see her writhing in pain,” says Namra.

She believes that a delayed decision by her mother to have herself examined was a major factor why she could not be cured. The other important factor was the long wait she had to endure for her examination at the Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital. “We would also get conflicting treatment advises from different hospitals and doctors,” Namra says.

Naina Khalid, a 26-year-old private school teacher, has somehow managed to survive this muddle of a diagnosis and treatment process.

She felt a small lump in her right breast in 2017 but she dismissed it as an infection and went about her life as usual. Soon she felt as if needles were pricking the lump. So, on the advice of a relative, she went to a private healthcare facility located in Lahore’s Defense area for her examination.

A doctor there conducted a biopsy of the lump and, as she puts it, assured her that she “most certainly did not have breast cancer”. Without doing any other diagnostics to rule out the cancer entirely, he removed the lump the same day through surgery and sent her home without any further advice.

Three years went by during which she never experienced anything abnormal other than occasional pain in her breast. In March 2020, she felt light-headed while teaching and then collapsed on the floor unconscious. She still did not realize that this could be because of the lump in her breast.

In October that year, Naina felt that the lump was growing and the pain in her breast was increasing. She immediately went to Lahore’s General Hospital, a government institution, for a checkup. On 11th November 2020, she was diagnosed with breast cancer.

She eventually got admitted to the Institute of Nuclear Medicines and Oncology (INMOL), a Lahore-based cancer treatment facility that works under the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC). The doctors there started her chemotherapy immediately -- all financed by the hospital. “I only had to pay 20,000 rupees for the initial tests,” she says.

Though she lost her shiny black and long hair during her treatment, she is happy that she has been cured of the cancer.

Deadly numbers

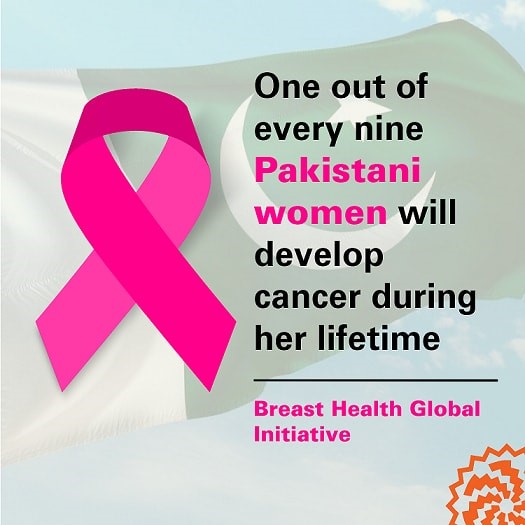

A study by the Breast Health Global Initiative, an international health alliance that develops evidence-based guidelines for breast cancer control, fears that the prevalence of breast cancer could assume alarming proportions in Pakistan. “The probability is that one out of every nine Pakistani women will develop cancer during her lifetime,” it states.

The report also shows that “breast cancer is more common in young females [in Pakistan], in contrast to the West, where it occurs after the age of 60 years, on average”. Pakistan is also reported by the same study to have 5.2 time higher rate of breast cancer incidence and 2.8 time higher rate of death from breast cancer as compared to these rates in the rest of Asia.

Other statistics paint an equally bleak picture. The Breast Health Global Initiative study reports that the number of new breast cancer patients in Pakistan was anywhere between 34,038 and 90,000 in 2017. (The wide difference between the two numbers is owed to the fact that Pakistan does not have consolidated country-wide data – more of which will come later.) It also records 16,232 deaths of breast cancer patients in the same year.

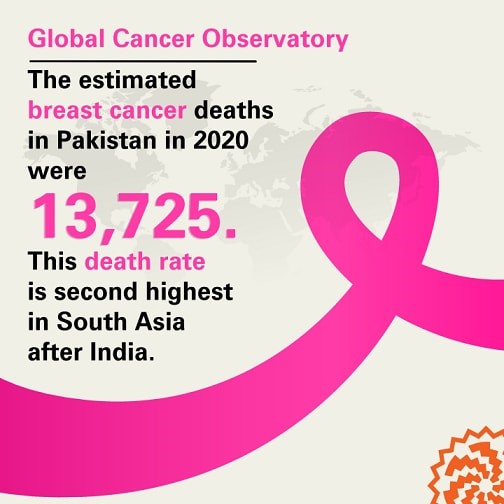

Global Cancer Observatory, a joint initiative of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), similarly, suggests that the estimated breast cancer deaths in Pakistan in 2020 were 13,725 -- second highest in South Asia after India.

The primary reason for this high mortality rate, according to the Breast Health Global Initiative study, is that 50 percent of the breast cancer patients in Pakistan get the diagnosis at an advanced stage of the disease. This is also very obvious from the ordeals of three Lahori women narrated above.

A study conducted in January 2019 by the Punjab Institute of Nuclear Medicines (PINUM), a government hospital located in Faisalabad, tried to identify reasons behind this delay. Involving 200 respondents, it found reluctance by breast cancer patients to get tested – a process known as ‘presentation’ in medical terminology – as the single most important factor causing the delay.

A similar study carried out jointly by Karachi’s Aga Khan University Hospital and Kiran Cancer Hospital, also located in Karachi, looked into the cases of 499 female patients who had contracted breast cancer between February 2015 and August 2017. A staggering 69.9 percent of them had stage three or stage four cancer – suggesting a clear delay in their diagnosis.

The study found that 55.2 percent of them had felt a breast lump but they chose not to seek medical attention. Another 26 percent were hindered from seeking treatment by social pressures such as the possibility of straining their relations with their husbands.

A national breast cancer screening program can facilitate an early examination of women who find it difficult to travel to hospitals for a variety of reasons, says Cancer Reports, an international, open-access, online journal that focuses on cancer research. Such a program can also identify the symptoms of breast cancer at early stages and can, thus, bring down the number of deaths from it, the journal states.

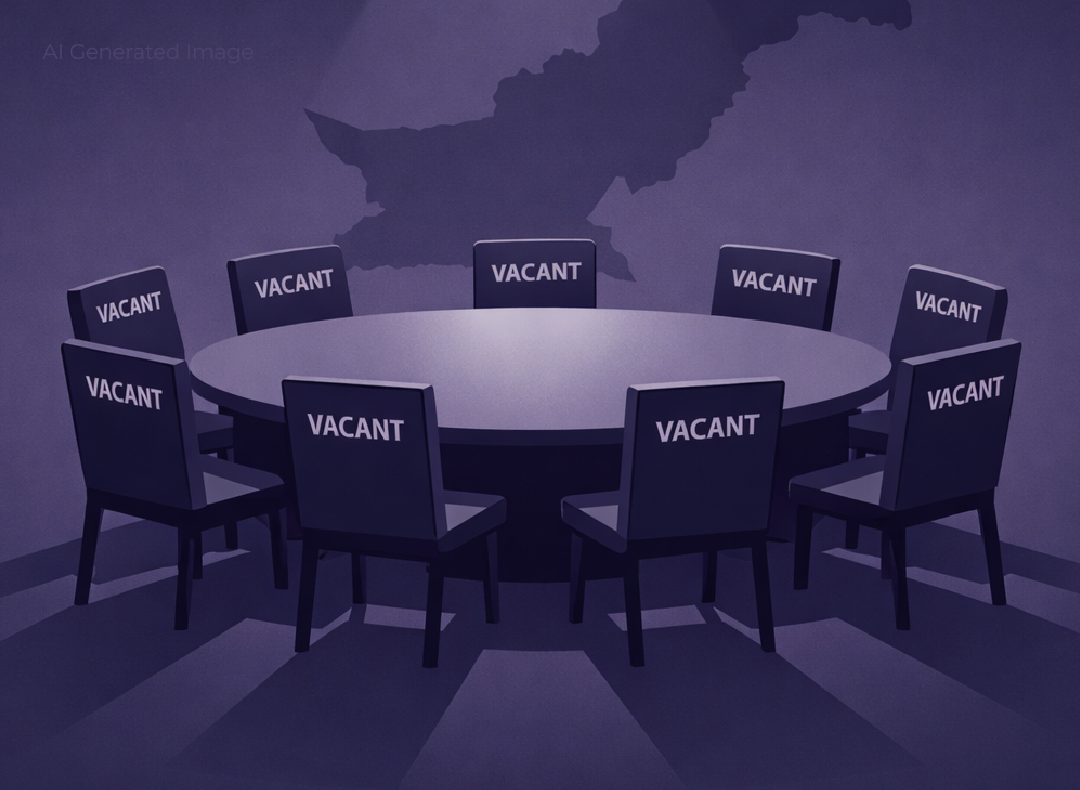

This program, however, does not exist in Pakistan. In its absence, breast cancer has been spreading rapidly in the country.

A PAEC report shows that it is now one of the most prevalent cancer types in Pakistan. Based on numbers gathered from 18 hospitals and laboratories affiliated with PAEC across Pakistan, the report states that 102,022 new cancer patients, both male and female, were identified between 2015 and 2017. Out of these, 22.6 per cent had breast cancer. From among all the 57,213 female cancer patients identified during this period, 22,599 (almost 40 percent) were suffering from breast cancer.

The report also shows that the number of breast cancer patients admitted in the PAEC-affiliated cancer treatment institutions in 2018 and 2019 was higher than the number of those suffering from any other type of cancer.

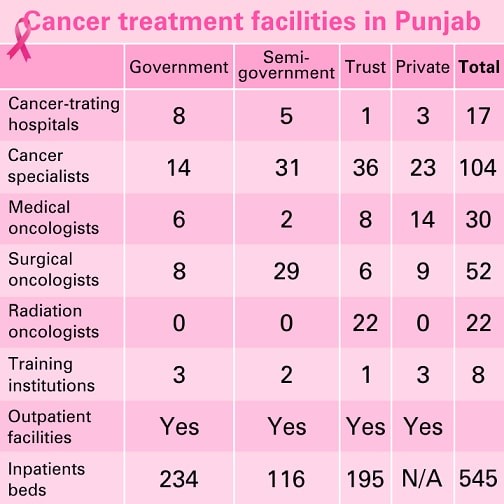

Most of the breast cancer patients in Pakistan are treated at government hospitals which, due to inadequate budget allocations, often do not have the required facilities. Cancer Reports reveals that, on average, one medical oncologist deals with almost 17,000 cancer patients and one radiation oncologist deals with 12,500 cancer patient in Pakistan during his/her entire practice. Even in Punjab, where medical facilities are supposed to be better than in the rest of the country, an oncologist examines 1,300 to 1,500 patients each year on average.

The need for a national registry

Pakistan has three mutually exclusive registries to collect, analyze and interpret data to help the government draft policies to handle cancer. These are: Karachi Cancer Registry which covers only the city of Karachi – or around eight per cent of the country’s total population; Punjab Cancer Registry, sponsored and supervised by the Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital; and Pakistan Atomic Energy Cancer Registry, set up by PAEC under a federal government initiative called the National Cancer Control Programme.

Though Punjab Cancer Registry became operational in 2008, it still covers only Lahore district which contains around 10 per cent of the total population of Punjab province. The registry has 27 collaborating healthcare facilities – 18 of them being in Lahore city alone.

Also Read

Free healthcare: Does the official plan work?

The Pakistan Atomic Energy Cancer Registry has 18 affiliated healthcare institutions. Spread all over Pakistan including Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan, these facilities treat 80 per cent of Pakistan’s cancer patients. This registry has been collecting data since 2015 though its first report for a three year period -- 2015-2017 – was published only in 2019. Its latest report, published in June 2021, similarly does not have current statistics and instead carries numbers pertaining to 2018-2019.

Dr Muhammad Sohaib, PAEC’s director of nuclear medicine and oncology, points to the lack of financial and human resources as the reason for these data gaps. “In the absence of these resources,” he says, “it becomes often difficult to communicate with the affiliated institutions and receive updated and conclusive data from them on time,” he says.

As far as a single national cancer registry is concerned, the federal government approved its establishment as far back as 2015 yet its remit remains limited to only eight major government hospitals.

According to Dr Ghulam Nabi Kazi, a public health specialist who also advises the Ministry of National Health Services, the reason why the national registry has so few affiliated institutions is the existence of other registries which, together, cover all the major cancer treatment facilities in the country. “Their existence means that a vast number of cancer patients are being treated outside the national registry’s remit,” he says.

He, however, believes that a truly national registry is a key component in ensuing cancer control. He, therefore, stresses upon the need for regularly collecting, compiling and crunching reliable country-wide cancer statistics instead of gathering and releasing sporadic and regionally disjointed numbers. Such comprehensive data, he says, is “essential to target the population most vulnerable to the risk of developing cancer”.

This targeted intervention may, in turn, protect many Pakistani women who have the probability to contract cancer in their lifetimes.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 26 Jul 2021, on its old website.

Published on 10 Jun 2022