Peter Jacob is extremely worried. “The time is approaching when religious minorities will stop existing in Pakistan,” he says.

As the head of the Peoples Commission for Minorities’ Rights, a civil society initiative, he comes across horrifying stories involving the denial of rights to non-Muslim Pakistanis on a daily basis. “The latest census already tells us that the population of religious minorities has decreased over the years.”

This, according to him, is a clear indication that non-Muslim Pakistanis are not happy with being taken for granted, mistreated and exploited and, therefore, are leaving the country.

Peter Jacob makes these observations while talking about what he calls a lack of sensitivity shown by the Sindh High Court in the case of Arzoo, a 13-year-old girl from Karachi taken as a wife by a much older Muslim man. Irrespective of the fact that her parents have an authentic proof of her age – one that is provided by the government’s own National Database Registration Authority (Nadra) – a two-member bench of the high court allowed her purported husband to take her with him on October 29th.

As almost every human rights activist has subsequently pointed out, the law prohibiting child marriage explicitly states that marrying a child – even with her consent – constitutes rape and is punishable as such. Why the judges chose to ignore this legal provision while giving the child in the custody of someone whom her parents accuse of having abducted her is anybody’s guess.

Since then a video of Arzoo’s wailing mother, Rita, has been doing the rounds on social media. She can be heard, mourning outside the Sindh High Court and pleading to the judges to return her daughter to her.

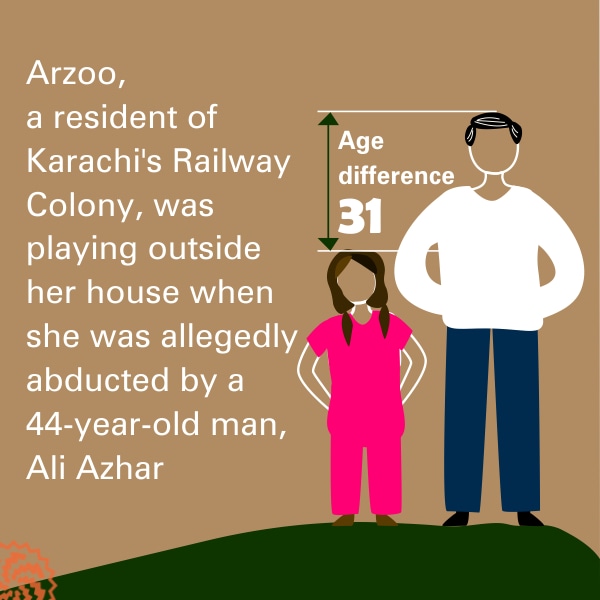

Arzoo is reported to have been playing outside her home in Railway Colony in Karachi’s District South when Ali Azhar, a 44-year-old man, allegedly abducted her. Her parents, Rita and Raja Lal, immediately reported to the police that their daughter had been abducted by some unknown person. A first information report was duly registered by the Frere Hall Police Station and some police officials posted there also tried to raid the house of Ali Azhar to retrieve Arzoo.

Ali Azhar, in the meanwhile, approached the Singh High Court to seek protection against the police action. The court not just approved a pre-arrest bail for him but also ordered the police station where his house is located to provide protection to Arzoo so that she is not taken away from him.

The only document that Ali Azhar presented to prove that Arzoo was an adult was an affidavit ostensibly signed by her. It states that she is 18 years old and that she has converted to Islam by her own free will.

What does the law say?

Arzoo’s case highlights why making laws to protect the marginalized sections of the society is only half the job done. The other half – and, as suggested by this particular case, the more important one – is to ensure the implementation of these laws both in letter and spirit.

Sindh, where Arzoo lives, indeed, has a law that delegitimizes child marriages. The province’s Child Marriage Restraint Act 2013 states in no ambiguous terms that marrying a child is a crime. This act also lays down clear punishments for anyone marrying a child as well as for those who facilitate that marriage.

At the Sindh High Court, the judges might have adhered to the letter of this law by seeking a proof of Arzoo’s age and getting it in the form of the signed affidavit. They, however, do not seem to have followed the spirit of the law because they did not seek an independent verification of both her age and the authenticity of her free will to leave the religion of her parents.

Karachi-based lawyer and human rights activist, Jibran Nasir, says the high court also did not give an opportunity to Arzoo’s parents to present their case even though they were present in the courtroom. Instead, the judges – again seemingly going by the letter of the law – did what the courts are supposed to do to provide protection to those who allege harassment by police. They could have first ascertained the nature and severity of the allegation against the person whom they provided the protection but they chose not to.

Since Arzoo is a child, subjecting her to sexual intercourse is deemed by the law to be statutory rape. Have the judges, thus, allowed her rape to take place by letting Ali Azhar take her with him? Jibran Nasir states in his tweet: “Now it is on the judges if anything happens to the girl.”

Talking to Sujag, he says he filed a petition at the court of a civil judge-judicial magistrate in District South on November 30th, on the behalf of Arzoo’s parents, pleading that Ali Azhar’s house be searched and girl be sent to a shelter home. The judge did not accept his plea even though a police official verified that her birth certificate that her parents have is genuine. He instead cited the Sindh High Court order to rule that protection had already been provided to Arzoo. “This shows how one court order can become the basis for the subsequent exploitation of a child,” Jibran Nasir says.

The question of free will to convert is also a moot point. Can a young girl belonging to a religious minority exercise her free will while being in the custody of a much older man who can easily turn her refusal to convert into a religious issue involving blasphemy? Once this question has been answered, another one starts looming large: can a girl even forcibly converted to Islam become a non-Muslim again? The legal answer to this question can be incendiary which clearly shows that judges often have religious considerations in mind -- rather than legal ones -- while deciding the cases of forced conversion.

As Sulema Jehangir, a lawyer and human rights activist, wrote in an April 2020 opinion piece published in the daily Dawn: “The fact that the default legal system in Pakistan is discriminatory, particularly towards women from religious minorities, coupled with the clout and resources of those preying upon them, implies coercion and urgently requires positive legislation to safeguard vulnerable citizens.”

A 2014 report by the Movement for Solidarity and Peace (MSP), a non-partisan organization devoted to research, education, and advocacy for human rights in Pakistan, says about 1,000 Pakistani women are forcibly converted to Islam every year. The authorities, on the other hand, mostly live in denial.

Senator Anwarul Haq Kakar, the head of a parliamentary committee, for instance, told a press conference a couple of weeks ago that most cases of forced conversion that his committee has investigated “have some degree of willingness on the part of the girl.”

Also Read

What’s in a name? Many Christians find their religious identities changed in NADRA records

Peter Jacob poses a pertinent question here: “They say that the victims of forced conversion are not forced so I ask them why suicide is a crime then because it is too done by someone out of their free will,” he says. “We need to look at the external pressures which lead someone to commit suicide -- as much as we need to do the same in cases of forced conversion.”

In a society that promotes the oppression of the weak and the marginalized and where laws are tilted in the favour of the powerful, he says, those belonging to religious minorities have no choice but to accede to the demands of their tormentors.

Arzoo’s parents can vouch for that.

Their lawyer Jibran Nasir says he is all set to move the Sindh High Court today (Monday) – citing the need to urgently retrieve a child bride from her abductor. In his application, he is seeking the girl’s production before the judges and asking for a re-verification of her age.

Will his plea be granted?

Only the judges who can interpret and implement both the letter and the spirit of the law – and that too simultaneously -- will be able to do that.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 2 Nov 2020, on its old website.

Published on 21 May 2022