All you can see is one eye, a flickering, fearful and frantic eye, constantly in motion. All the rest of *Saifullah’s body is wrapped in white bandages.

On a typically dry hot day in Multan, he was walking on a shabby street near Vihari Chowk to go back home to meet his five children. An accountant by profession, he was hoping to convince his family to accept a woman as his second wife. He had been pursuing her for years.

Suddenly, a stinking liquid was splashed on his face and body and the last thing he heard were screams and cries coming out of his own mouth. It was acid -- thrown on him by his first wife.

The attack was carried out on 29th August, 2020 at around 5:30 pm.

A month later, Saifullah, 51, is still admitted in the Burns Unit of Nishtar Hospital, Multan’s largest public sector healthcare facility. The whole of his face and torso, except a restless eye, are full of blisters. Any mention of the day when he was attacked causes tremors in his body. Outside the burn unit, his second wife, and his 24-year-old daughter from the first wife are both praying for his life.

“We cannot believe that our mother’s anger could ever translate into this horrific revenge. Look at my father; he is so burnt that you can see his bones under his flesh when the hospital staff changes his bandages,” his daughter tells Sujag.

New targets

As is obvious from Saifullah’s case, acid has become a weapon of choice for many intending criminals. This incident also indicates that the nature and extent of acid attacks has considerably changed in recent time. Seen previously as a gendered crime targeted particularly against women, they are now being used against men and children as well.

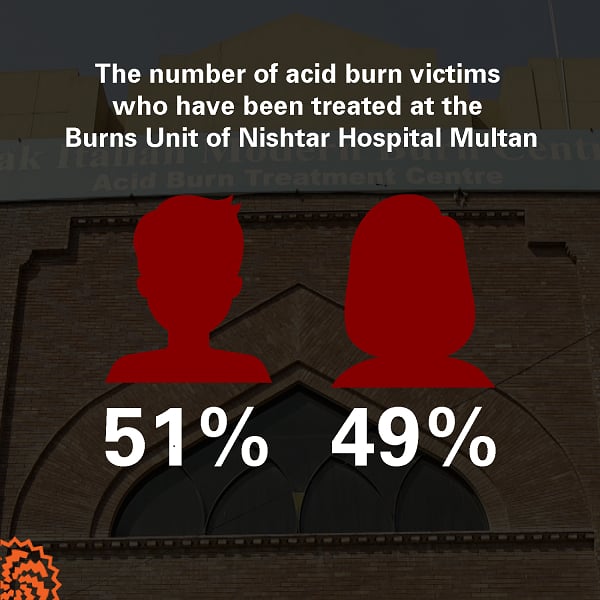

This is also borne out by hospital data. Out of a total of 115 acid burn victims who have been treated at the Burn Unit of Nishtar Hospital so far, 41 are women and 59 are men.

The following cases – all having happened in 2020 – illustrate the same change:

On July 15th 2020, a few young men in the central Punjab city of Mandi Bahauddin threw acid on their uncle over a property dispute.

On the same day, in Sadiqabad area of Rahim Yar Khan district, Qari Usman, a religious teacher, threw acid on four children in his madrassa because they had accused him of abusing them. The children suffered multiple burns and have been hospitalized since then.

In June 2020, five men threw acid on their sister-in-law over a domestic dispute in Shah Sadar Din village of Dera Ghazi Khan district. The woman was shifted to a hospital in critical condition.

Malik Khalid Mehmood, a senior lawyer based in Multan who has also served as a sessions judge, quotes a similar case of revenge in which acid was used to brutal effect. He says:

“A woman named Jahanara Bibi sought divorce from her husband through a court when another man named Riaz promised to marry her.

After her divorce, however, Riaz decided to not marry her and stopped visiting her again. Infuriated, Jahanara called him one last time. The morning after, while Riaz was taking a shower, Jahanara who had kept a bucket full of sulfuric acid in the bathroom, spilled it on him. ”

Riaz’s entire body was badly burnt and he died in a few hours. Jahanara later confessed to her crime and was handed death penalty for carrying out planned manslaughter.

The use of acid as a weapon has been reported from some contemporary war zones as well. On April 4, 2017, in a rebel-held town in north-western Syria, dozens of people were showered with a variant of phosphoric acid. Their accounts are not very different from the ones cited earlier:

“I lost consciousness. I couldn’t breathe anymore; it was like my lungs were shutting down,” recalled one victim in an interview with Al-Jazeera.

The living dead

Saifullah’s first wife presented herself to the police right after throwing acid on him but she is still convinced that his betrayal in love had to be punished in a manner worse than death.

She is not the only one who thinks this way.

On 25th September 2020, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, an anti-Shia organization banned by the government, issued a deadly warning to academics, journalists and Shia religious leaders who speak against sectarian killings in Pakistan. It stated: “In order to make an example out of these infidels, some of these must be attacked with acid. We will make them the living dead.”

The state of seven women, three men and one child, who suffered from acid burns in 2020 alone in Multan and its adjoining areas – where more acid attacks are reported than anywhere else in Pakistan -- testifies that they feel exactly the same way: as the living dead.

“Death would have been much quicker and less agonizing. This life is worse than death,” says an embarrassed Farhana who lives in a slum in the heart of Multan.

She was attacked by her husband for refusing to accept a marriage proposal for her daughter. She was walking on a street when he threw acid on her which burnt her entire face, deforming her lips, nose and one eye. Reconstructive surgeries have restored some of her face but she still cannot see from one eye.

“I have been living in this neighbourhood for 25 years and still people look away when they see me. Women rush inside their homes when they see me in the street and the children running in the street make fun of me,” she tells Sujag.

One of the main reasons for using acid as a deadly weapon is that purchasing a gun is expensive and requires a lot of effort to clear official checks and balances on its sale and purchase. Even illegal weapons are difficult and costly to acquire and leave their forensic footprint which can be used against the perpetrator of a crime during trial.

Easy availability

Acid is easy to get, and even easier and more efficient to use. Sulfuric acid, hydrochloric acid, black acid and even the acid used for drain opening are not just available over the counter almost everywhere in Pakistan but they also sufficiently harm their target.

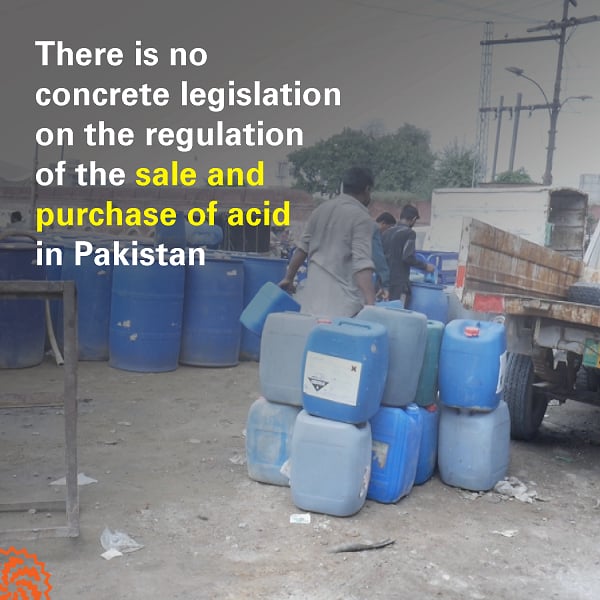

While there are laws for punishing the crime of throwing acid on someone, there is no concrete legislation on regulating its sale and purchase. Activist and policy adviser Gul Hassan, who runs the Initiative for sustainable development, an organization based in Lahore, cites the easy availability of acid as the main reason for acid crimes.

“It is available everywhere -- from the shelves of superstores to the corner shops in a street. People don’t realize how dangerous it is,” he says.

Advocate Khalid Mehmood says the same thing while talking about Jahanara’s case. “She chose acid because she could arrange to get it more easily than a weapon.”

A small bottle of the most corrosive acid – used in car batteries -- costs 50 rupees at Lahore’s acid selling market near Do Morya Pull. The market exudes an overpowering and pungent smell of various acids, stored in large blue plastic barrels. No guidelines or precautions are followed here for the transport or storage of these substances.

This market calls itself Asia’s biggest acid selling place, with hundreds of labourers handling dangerous, toxic and hazardous potions. They are not wearing any masks, gloves or any protective gear and are working in conditions which can easily qualify as highly hazardous for human health.

All types of acids are sold here freely.

When asked for Sulphuric acid, the owner of a shop here says he will need the purchaser’s identity card as that acid is only for industrial use but he doesn’t wait to add that he could dilute it a bit and give it to his customers without needing their identity cards. This diluted acid is still strong enough to dissolve human flesh and burn clothes.

Other types of acids are also easily available here. The most common among them are the ones used for opening drains and for putting in car batteries. These can easily be purchased as no law restricts their over the counter sale.

Also Read

The cover-up: Why a damning government report on Violence Against Women Center has been shelved

This is not to suggest that there are no rules and regulations at all for handling dangerous substances in Pakistan. According to the Punjab Hazardous Substances Rules 2018, there are strict guidelines for the transport and storage of dangerous chemicals like acids. Every type of acid, for instance, needs to be clearly labelled and stored in covered containers.

These rules, however, are never implemented. As Gul Hassan says: “Even though the sellers of chemicals cannot operate without licenses issued by the government, they face no restrictions on who they can sell these chemicals to. Thus, every kind of acid is sold freely. This has led to many accidents.”

In other countries, not just the hazardous nature of acids but their potential to be used in violent attacks has also been duly recognized. In the United Kingdom, where the incidence of acid attacks is the highest in the world, acid has been declared by law as a weapon of violence.

* The name has been changed to protect the victim’s privacy.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 5 Oct 2020, on its old website.

Published on 28 May 2022