Zafar Iqbal, 50, mortgaged his wife’s jewellery to cover the expenses he had incurred on his previous sugarcane crop. He also had to sell his three buffaloes to meet the everyday financial needs of his five-member family.

Iqbal owns six acres of land and has got another six acres on lease. He and his three sons grow sugarcane, rice and wheat crops on this land.

He cultivated sugarcane on three acres last year and sold it in three instalments to Pasrur Sugar Mill located in Pasrur town of Sialkot district. The mill’s management paid him promptly for the first two consignments (valued at 280,000 rupees) but the payment for the third consignment (amounting to 214,000 rupees) has not been made even now.

A middle level farmer from Lak village in Phalia tehsil of Mandi Bahauddin district in central Punjab, Iqbal had borrowed money from a Phalia-based trader, Muhammad Nadeem Anjum, to buy fertilizers, pesticides and seeds. He, however, could not return this loan due to the non-payment of his dues by the mill so he had to pawn his wife’s 2.5-tola (29.15 gram) gold jewellery to his lender.

Anjum himself is also a sugarcane farmer. The same sugar mill owes him 1.28 million rupees too. Its refusal to pay the dues has left hundreds of sugarcane growers in dire financial straits, he says.

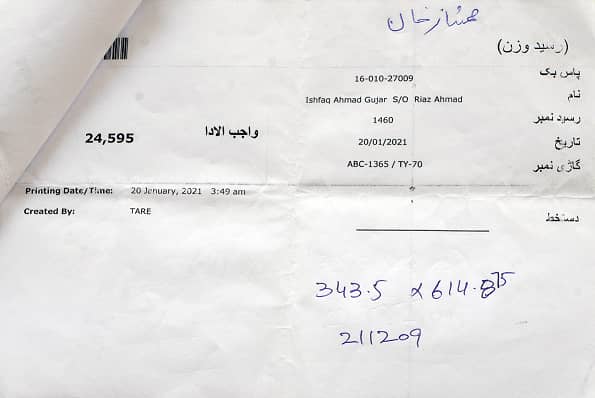

Ashfaq Ahmed Gujjar, 41, a resident of Ajnianwala village in Sheikhupura district, is one of these growers. He sold his entire previous sugarcane crop to Pasrur Sugar Mill but it is yet to pay him two million rupees in lieu of that. The mill, similarly, owes a collective amount of 3.4 million rupees to seven other farmers in the same village.

Imtiaz Ahmed Wahla and Naveed Husain Wahla, two brother who belong to a village, Chak-24 RB, in Sheikhupura district, also sold sugarcane worth 13.4 million rupees to Pasrur Sugar Mill. Like hundreds of other farmers, they are still awaiting payment for it.

Information gleaned from the office of Cane Commissioner Punjab, a government entity that monitors the sale and purchase of sugarcane in the province, shows that the mill owes a total of 44.59 million rupees to farmers in Mandi Bahauddin, Hafizabad, Sialkot, Sheikhupura, Nankana Sahib and Sargodha districts.

But Binyameen Ahmed, who worked as the mill’s cane manager in 2020 and 2021, says the amount of outstanding money is much bigger than the one reflected in the Cane Commissioner’s record. The commissioner, according to him, only knows about the money owed by farmers who have sent him applications for the clearance of their dues.

The actual price of the sugarcane that the mill purchased in 2020-21 but did not pay for, he says, stands between 120 million and 150 million rupees.

A lop-sided deal

The receipts which the mill management has issued to the farmers for the purchase of this sugarcane, however, have no legal value. The farmers call them kachi raseed or provisional receipts. These carry the name of the seller, the weight of the consignment, its price and its purchasing date but have neither the signature of any representative of the mill nor its official seal.

Issuing such receipts is a criminal offence under the Sugar Factories (Control) Amendment Ordinance 2020 which remained in force in Punjab between September 22nd, 2020 and March 21st, 2021. This law made it binding upon sugar mills to purchase sugarcane from growers only through Cane Purchase Receipts (CPRs) which the latter can use like a cheque to withdraw their dues from a bank within 15 days after selling their crop.

Pasrur Sugar Mill gave provisional receipts to growers instead of CPR but now does not accept these receipts as valid.

The law also stipulated that the owners and administrators of those mills which did not issue CPRs, delayed the payment for sugarcane purchases or were found involved in making undue cuts in the purchased sugarcane’s weight shall be liable to an imprisonment of five years and a fine of 500,000 rupees.

Muhammad Rafaqat, cane manager at Pasrur Sugar Mill, repudiates allegations that his employer has violated this law. “Our mill has not issued any receipts other than CPRs,” he claims and adds that “the receipts in the farmers’ possession, reflecting huge amounts of money outstanding against the mill, are all fake”. As he puts it, “making these slips is not a difficult task. Anyone with a computer and a printer can make as many of them as he likes.”

Rafaqat also claims that Pasrur Sugar Mill has cleared all its sugarcane purchase dues. “Even then if a farmer has an unpaid CPR, he must produce it so that he can be paid immediately.”

Sugarcane farmers such as Zafar Iqbal, however, call these claims a blatant lie. He says even when the mill paid him for his first two consignments, it was not done through CPRs but through kachi raseed.

Shahbaz Ahmed Lak, a member of the Phalia chapter of a farmers’ organisation, Kisan Board Pakistan, supports this stance. He says sugarcane farmers continuously demanded that the mill’s management should purchase their crop through CPRs. They, however, were told that CPRs could not be issued because the mill was purchasing sugarcane at a higher price than other mills but did not want to bring this price on record.

The mill’s management, on the other hand, kept on assuring the farmers that their original CPRs were in its safe custody and would be provided to them whenever required, he says.

Mentioning the same assurance, Naveed Husain Wahla says the farmers held a meeting with the mill’s general manager, Fateh Muhammad, as the sugarcane purchase season came to an end in April 2021. They urged him to either pay their arrears immediately or provide them their CPRs. He told them that all their dues would be cleared in a couple of days so they would not need their CPRs at all.

Wahla says the mill’s then cane manager, Benyameen Ahmed, was sacked just because he also supported the farmers’ demands. “Even then he joined the protesting farmers in a meeting with the mill’s management where he reiterated his demand for the issuance of CPRs”.

He also submitted a written statement to the Cane Commissioner wherein he confirmed that the mill management had not only issued receipts other than CPRs to sugarcane farmers but also had not paid tens of millions of rupees to them.

Ahmed says he was bound to raise his voice for the farmers who had trusted him and sold their crop to Pasrus Sugar Mill. “Had I not persuaded these sugarcane growers, many of them living far away from Parur, to sell their sugarcane to the mill, it would not have been able to even start functioning,” he says. This, according to him, owed to the fact that majority of the farmers in the mill’s surrounding areas had stopped cultivating sugarcane sine long (mainly because it had remained closed for more than 18 years).

Data collected by Crop Reporting Service, a subsidiary of Punjab government, verifies what Ahmed says. It states that, till 1991-92, sugarcane was cultivated on an area of 140,800 acres in the four districts around the mill: Sialkot, Gujranwala, Narowal and Gujrat. In 2019, the area under sugarcane cultivation in the same districts had shrunk to only 16,000 acres.

The search for justice

Frustrated by the mill management’s refusal to clear their dues, the farmers later presented their demands to Sialkot’s district administration -- but all in vain. This was despite the fact that the Sugar Factories (Control) Ordinance, 2020 authorises deputy commissioner, the administrative head of a district, to not only arrest a mill owner for delaying payments but also seal his mill.

Wahla brothers also lodged a First Information Report (FIR) with Pasrur City Police Station on April 16th, 2021 in which they stated that the mill had unlawfully withheld the payment of 10.09 million rupees due to them. The police, they say, is yet to take any action upon this FIR.

A large number of farmers, meanwhile, submitted separate complaints to Cane Commissioner Muhammad Zaman Wattoo who, in turn, sent several notices to the mill management in order to address these complaints. None of those notices was responded to.

Consequently, he issued an order on July 9th, 2021 that a case would be filed against the mill management for violating various provisions of the Sugar Factories (Control) Act, 1950. He also stopped it from selling the sugar it had produced. The mill management promptly challenged this order before the Lahore High Court (LHC).

Ten days later, according to Naveed Husain Wahla, Additional Cane Commissioner, Syed Sibte Hassan Sherazi, appeared before the court. He told its judge, Justice Muhammad Sajid Mehmood Sethi, that the Cane Commissioner’s office had received 27 complaints from as many farmers who had alleged that Pasrur Sugar Mill was not paying their dues. The total amount of money the mill owed to the complainants stood at 38.676 million rupees, Sherazi stated.

Also read

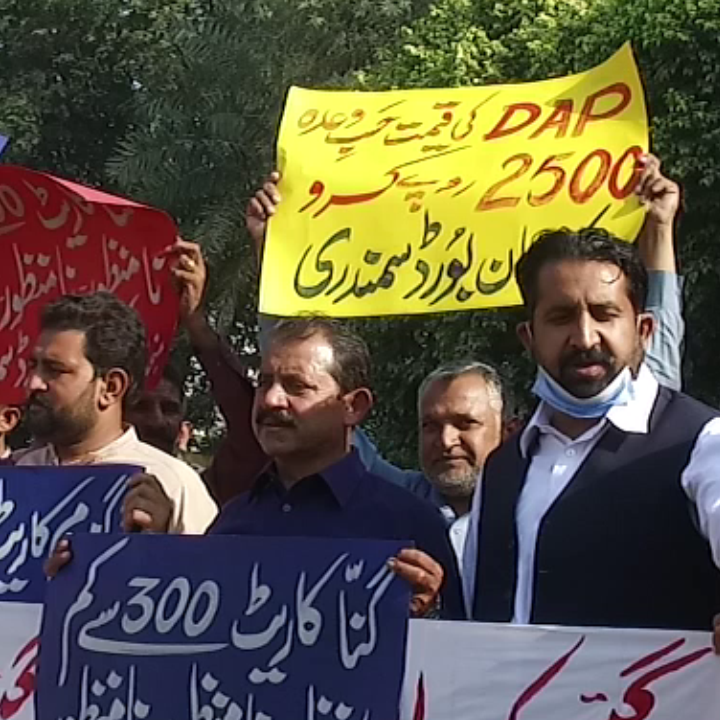

Corporate profit vs farmers' plight: Why DAP fertilizer price has risen sharply over the last one year

The panel of lawyers representing the mill took the plea that their client had no legal obligation to respond to those complaints since the complaining farmers did not have any CPRs with them.

After hearing the two sides, Justice Sethi directed the Cane Commissioner to resolve the issue within four weeks. He also ordered the mill management to deposit a cheque for the disputed amount to the Cane Commissioner as security so the farmers could be paid immediately if his decision went against the mill management.

The mill’s lawyers, however, informed the court that they would not give the cheque to the Cane Commissioner because they feared that he might make payments to farmers even before a final decision in the case. The court, then, ordered them to submit the cheque with LHC’s deputy registrar (judicial). It also revoked the Cane Commissioner’s order that had restrained the mill from selling its sugar in the market.

Three months have passed to this order but the farmers are still awaiting its implementation.

Making profit at the growers’ expense?

Established by the Pakistan Industrial Development Corporation in 1976, Pasrur Sugar Mill was originally a state-owned enterprise. It was privatised in 1985.

Ikramul Haq Sajid, who has 30 years of experience of working on administrative positions in sugar industry and has also worked with Pasrur Sugar Mill as its general manager in 2019-20, says it was first purchased by a leading Pakistani business house, United Group. But that group closed it down in the late 1990s due to financial crunch, he says.

Later, Shakeel Mahmood Bhatti, owner of Chishtian Sugar Mill, bought it. But, according to a report published in Urdu daily Nawa-i-Waqt on July 24th, 2010, the then Chief Justice of Pakistan, Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry, directed the Punjab government to submit a detailed report regarding its sale.

He was hearing a petition filed by one Pervez Bajwa who alleged that Bhatti and his business partners had connived with Punjab revenue department to falsely show 150-arce real property owned by the mill as agricultural land. This land, he said, was then sold to the directors of Bhatti’s own company through a secret auction at a throwaway price of 21.3 million rupees even though its actual price was in billions of rupees.

This controversy halted the resumption of the mill’s operations. The chances of such a resumption became even more meagre when Bhatti was gunned down in 2011 in Lahore.

A business tycoon from Lahore, Sheikh Ahmed Latif, purchased the mill eventually. His brother, Sheikh Ahsan Latif, is the son-in-law of Lieutenant General (retired) Khalid Maqbool who served as the governor of Punjab under the military regime of General Pervez Musharraf.

The farmers allege that the mill owners are refusing their payments because of their political and social influence. Otherwise, they point out, its sale and purchase record clearly suggest that it has earned enormous profits.

This record shows that Pasrur Sugar Mill purchased a total of 50,892 metric tons (50.892 million kilograms) of sugarcane in 2020-2021 which yielded 3,805 metric tons (3.805 million kilograms) of sugar. If the official price of sugar (85 rupees per kilogram) is taken into account, the total value of the sugar produced by the mill amounts to 323.45 million rupees. In addition, the sale of bagasse, mud and molasses also earned its owners several million rupees more.

Published on 25 Oct 2021