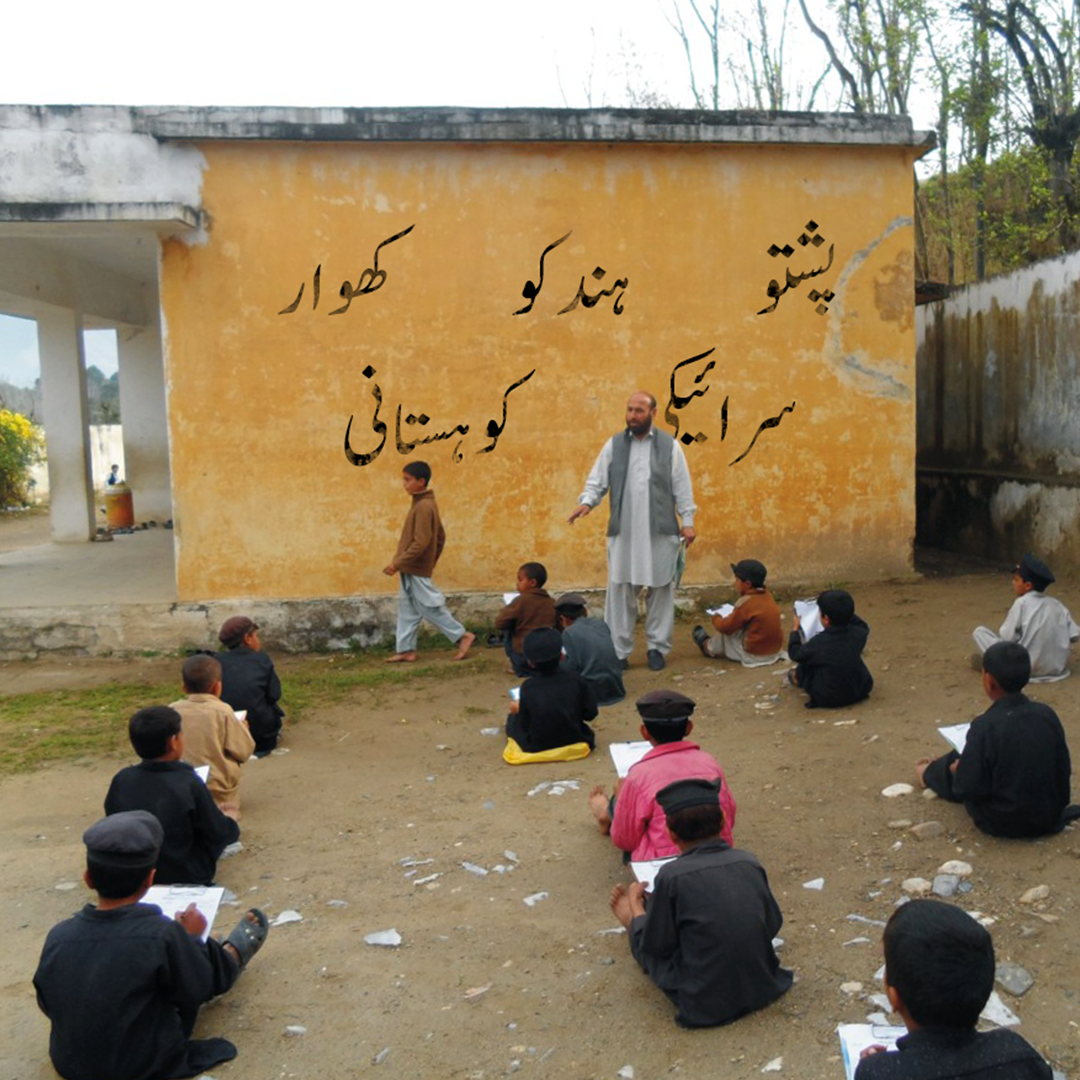

Ismatullah, a fifth grader at a private school in district Khyber, has studied Pashto as a subject since his first grade. That’s why it is easy for him to read and write in his mother language. However, most of his classmates have attended such schools that had no arrangement to teach Pashto. During the visit of the Lok Sujag, Ismatullah was reading to his classmates the poem, Hujra, from the Pashto book.

Muhammad Furman, the principal, says Pashto has been taught as a compulsory subject at the primary education level since 2018 at their school and a child can easily learn to read and write in his or her mother tongue within five years.

In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the decision to make mother tongues a compulsory subject for primary classes (grade one to five) was made by the Awami National Party government in 2011. The provincial assembly passed the Pakhtunkhwa Supervision of Curricula,

Textbooks and Maintenance of Standards of Education Bill, 2011 on April 26, 2011, which became an Act in May of the same year after the governor’s approval. Initially, it was decided to teach five mother tongues as compulsory subjects in the province, namely Pashto, Hindko, Seraiki, Khowar (Chitrali) and Kohistani.

Before this law, there were courses available for teaching Pashto from the first grade to Master's level but for the other four languages, even the alphabet had not been decided. A senior official from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Textbook Board, responsible for publishing textbooks says, on condition of anonymity, that preparing the textbooks for mother tongues was a very challenging and complex process.

“During the preparation of the curricula for Khowar and Kohistani languages, there were differences among the local scholars and teachers,” he says and adds that after a lengthy process of consultation, the people of Chitral agreed on Khowar curriculum but the Kohistani curriculum is still to be developed.

“By 2016, we had prepared the courses for all the mother tongues except Kohistani, and that year, the teaching of Pashto, Hindko, Seraiki and Khowar began from the first grade and it is now being taught up to the eighth grade. In the new academic year, textbooks for the ninth grade will also be provided to the students,” the official added.

Curriculum, textbooks and teachers

The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Textbook Board has already received requisitions from public schools for mother tongue textbooks for the new academic year. According to details, gathered by Lok Sujag, the public schools have sought 27,500 Pashto books for the ninth grade, 1,820 Khowar books, 1,200 Seraiki books and 690 Hindko books.

Dr Inayatullah Faizi, a Khowar language expert and researcher, is amazed at the numbers as in 2011, the number of Khowar speaking children in schools was 120,000, which has now increased to more than 150,000 while on the other hand, the demand for ninth-grade textbooks is less than 2,000.

Dr Qaiser Anwar, the controller of the Dera Ismail Khan Board of Intermediate and Secondary Educational, who played an important role in the preparation of the Seraiki curriculum, also believes that the demand for Seraiki textbooks from schools is very low compared to the number of Seraiki speaking children.

Ziauddin, the general secretary of the Gandhara Hindko Board, Peshawar, and the chief executive of the Hindko Academy, established on a public-private partnership basis, draws attention to another issue.

“We already had Pashto teachers in public schools but teachers for Hindko, Seraiki and Khowar languages have not been recruited. Having someone teach these languages just because they are the native speakers is a waste of the children’s time.”

Dr Inayatullah Faizi agrees with him, saying, “Without hiring proper teachers of these languages, it is not possible to develop them or increase the number of speakers.”

Do private schools teach only Pashto?

In all public schools, the children are provided with textbooks for mother tongues free of cost just as other textbooks. However, private educational institutions have to purchase these books from the market. According to the KP Textbook Board, the books for private institutions are provided to specific booksellers based on their demand and the private schools buy the book from there. However, according to the board, no demand has been made for any books other than Pashto across the province, which means that most private institutions are teaching only Pashto and not any other mother tongue like Hindko, Seraiki or Khowar.

Asad Khan Natt, a fifth grader at a private school in Nothia Qadeem, Peshawar, says that he is taught Hindko at his school even though his native language is Pashto. He finds Hindko quite difficult to learn. There is also no dedicated teacher for Hindko at the school.

The school principal, Javed Hussain, explains that his school has children from different language backgrounds, with Hindko speakers being the majority; therefore, Hindko is taught to all the children until the fifth grade.

The evidence suggests that private schools are not fully adhering to the policy of teaching mother tongues. Lok Sujag contacted the officials of the Private Schools Regulatory Authority several times to get its version on the issue but received no response.

Why is Kohistani not being taught?

Out of the five regional languages taught at schools, Khowar is spoken in Upper and Lower Chitral, but apart from this, there are 12 other languages spoken in the area. During the preparation of the curriculum, the speakers of these minority languages raised concerns about their children learning Khowar, but eventually, everyone agreed to adopt it. The speakers of Khowar are the majority.

However, the people of Kohistan could not reach such an agreement. Talib Jan Abasindi, who has been researching the Kohistani language for the last 26 years, told Lok Sujag that when the provincial government made mother tongues a compulsory,

Kohistani was mentioned in the official document. But four languages are spoken in Kohistan and two most widely spoken languages are Shina Kohistani and Abasin Kohistani. Shina Kohistani is spoken in Eastern Kohistan while Abasin Kohistani in Western Kohistan, he says and adds that the population of speakers of each language is about 500,000.

He explains that when the process of determining the alphabets and curriculum for the Kohistani language began, a conflict arose between the two parties and the matter reached the Peshawar High Court in 2014. The court gave a ruling in 2020, giving the chief secretary of the province the authority to resolve the issue, but this has not been settled yet. Therefore, Kohistani is not yet included in the curriculum.

Kalasha faces threat of extinction

Talib Jan Abasindi explains that Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is the province with the highest number of languages spoken in it compared to the rest of the country. It has 27 local languages (some experts give the number as 30). “The larger languages here have not been able to eradicate the smaller ones because the mountains and rivers have divided the linguistic groups in such a way that they have remained mostly confined to their areas and protected from the influence of others,” explains Talib Jan.

In addition to the five languages taught in the curriculum, other languages spoken in the region include Torwali, Burki or Ormuri, Gojri, Gawri, Kiala, Kalasha, Palula, Yidgha, Ghorbati, Shekhani, and Dresh.

According to the 2023 census, the population of Kalasha speakers is 7,466 in the whole country, and in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the number is 5,632 and they are living in three villages of Chitral.

Lok Rahmat, who belongs to the Kalasha tribe, is trying to preserve his language and culture. He says they have established an institution called ‘Kalasha Dur.’

“We have got 18 fundamental books written for its development and promotion but the government has made no arrangements to preserve it. The Kalasha language is at risk of extinction, and if it disappears, a rare culture will vanish from the world.”

Terrorism and damage to Ormuri by terrorism

Malik Rafiullah, who works for the promotion and development of the Burki language, shares the same opinion as Talib Jan. He explains that the people of the Kaniguram Valley in South Waziristan have been speaking Burki or Ormuri for centuries, with a population of about 50,000. However, when the military operation was launched in October 2009, all of them migrated to district Tank in Dera Ismail Khan division, and other cities. Now, the children of the Burki tribes have learned languages such as Seraiki,

Pashto and others spoken by children from other areas but they are forgetting their own language.

Talib Jan Abasindi believes that the small languages in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have suffered severe damage due to climate change (floods), natural disasters (earthquakes), and terrorism, which forced people to migrate to their areas.

Accepting diversity to preserve languages

Pashto is the most widely spoken language in Swat but in Upper Swat, many people speak their mother tongues, including Torwali, Gawri, Gojri, Ushoji, and Khowar. Zubair Torwali, a resident of tehsil Bahrain in district Swat, who works for the development of mother tongues, also runs an organisation called the Institute for Education and Development (IBT).

He says that most people in the country consider Urdu, Pashto, Punjabi, Sindhi, Balochi, Seraiki, and Hindko as the only national languages while about 68 other languages are also a means of local communication, each carrying its own history and culture.

“If these (local languages) disappear, their history, culture, scientific treasures and indigenous wisdom will also vanish.”

Torwali believes that in the modern world, the narrative of uniformity is dying, and people are embracing diversity. “For national development, it is essential to move forward with people’s identities, languages, and cultures.

“The world has moved far ahead. In the UK, Punjabi is also taught as a mother tongue. But our country is still trapped in the narrative of modernity and colonialism where linguistic and cultural diversity is seen as a threat to national unity. We need to get over this obsession,” he stresses.

Published on 17 Feb 2025