This feature was commissioned by the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) as part of a series of profiles of sanitation workers across the country. These profiles are being released as part of the Shakeel Pathan Labour Studies Series, which documents working conditions across various labour sectors and provides policy recommendations advocating the right to dignity and decent work for vulnerable labour groups.

Minutes before she leaves for work, 40-year-old Shehneila* changes out of the cotton sari she prefers wearing at home and dons a white shalwar kameez. She then applies a dash of orange-red powder to the parting in her hair. The sindoor is a flame-shaped symbol of her privileged status as a married woman and she wears it with unbridled pride. This auspicious dot of vermilion is an abiding testament to her identity as a Hindu woman in a Muslim-majority country.

As she drapes a chaddar over her head, Shehneila doesn’t try to conceal the crimson mark and disguise this part of her identity. Whenever she commutes to work on her husband’s motorcycle, Shehneila has never felt that her sindoor attracts curious glances from passers-by.

‘The only reason I put away my saris and change into a shalwar kameez is because I can work easily in one,’ she admits.

Six days a week, Shehneila performs a nine-hour shift cleaning the women’s toilets at a private corporation on I. I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi’s business district.

‘I’ve been working here for almost a year,’ she says. ‘I haven’t been given a uniform to wear, even though the other cleaner, who works with me, has one. I will probably get one soon, but I’m not sure when,’ she says.

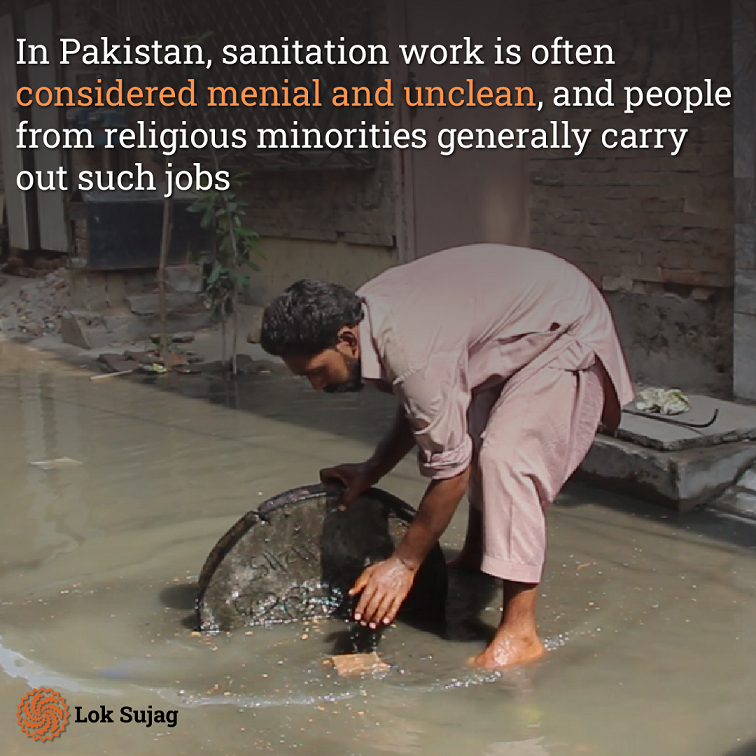

The shalwar kameez is, therefore, a convenient substitute for a uniform she has yet to receive from her employer. On some level, her decision to separate her work clothes from those she wears at home is an attempt to preserve her private life from the shadow of her professional obligations. But Shehneila’s isn’t just any ordinary struggle to establish a work-life balance. Sanitation work is often stigmatised in Pakistan and such tasks are usually performed by people from religious minorities. This is primarily because Muslims deem work that falls into this category ‘improper’ and ‘unclean’. Cleanliness, though, is at the heart of every faith. Hinduism also emphasises the virtues of external and internal cleanliness. Every day, numerous Hindu sanitation workers in Pakistan often compromise on their notions of physical cleanliness in a quest to feed their families.

‘We are provided all the supplies we need to keep the toilets clean,’ Shehneila says, ‘But we aren’t given soap or towels to keep ourselves clean during work.’

Making a clear distinction between her work and home clothes allows Shehneila to restore balance and achieve some semblance of spiritual cleanliness.

However, the absence of a uniform or opportunities to ensure personal hygiene seems like a trivial concern when compared to the other challenges she has reckoned with over the decades.

Journey through time

When she was younger, Shehneila never envisaged that she would be working as a commercial cleaner. She hails from a conservative Hindu family that had cultivated a home near Dayaram Jethamal Science College soon after they decided against migrating to India in 1947.

‘My maternal and paternal grandparents weren’t well off, but they managed to make ends meet by doing a few odd jobs,’ Shehneila claims. ‘My family was very strict and old-fashioned. Boys weren’t encouraged to study too much as they were expected to start earning. Girls, however, weren’t allowed to go to school at all. That’s why I have no formal education. I don’t even know how to sign my name.’

At the age of 17, Shehneila was plucked out of her father’s home and married off to a man from her community, as her parents believed marriage would allow her to fulfil her destiny. ‘They didn’t know what life had in store for me,’ she says, laughing.

Her husband, who was almost a decade older than her, had been hired as a sweeper at an oil-and-gas company through a third-party contractor.

‘He only earned a monthly salary of Rs2,200 back then,’ she recalls. ‘It was difficult for us to make ends meet on his salary. My husband had to work long hours, so he couldn’t work another job.’

In the years after her marriage, Shehneila gave birth to two children—a daughter and a son. Her husband’s financial standing wasn’t very strong and the couple often struggled to meet their children’s basic needs. Faced with these challenges, Shehneila realised that education opened the portal to opportunities and that her family’s opposition to educating girls had cheated her out of a brighter future.

‘I wanted to ensure that my children—especially my daughter—went to school,’ she says. ‘My extended family didn’t approve of my decision, but my husband understood the value of sending our children to school.’

In the absence of academic qualifications, Shehneila had to find her path to a comfortable life. ‘The only way to achieve this goal was if both my husband and I worked,’ she adds.

Nearly 20 years ago, Shehneila embarked on a quest for gainful employment that led her to initially take on work as a domestic cleaner. ‘I started cleaning at a two-storey house rented by two families,’ she says. ‘The begum sahib who lived downstairs paid me Rs600 per month while the one upstairs gave me Rs700 per month.’

Shehneila found it increasingly difficult to survive on this meagre salary. ‘In the evenings, I worked as a sweeper at a clinic run by a brain doctor in Karachi.’

Over the last two decades, Shehneila has worked as a sweeper at a large number of public and private offices. ‘I’ve cleaned toilets and scrubbed floors at banks, clinics and schools,’ she claims. ‘I briefly worked as a sweeper at Mowloo Juma Hospital as well.’

Many of these gigs came her way through a third-party vendor. As a result, she was hired on a strictly contractual basis and did not enjoy the privileges that a permanent employee would. Shehneila’s sole motivation for all the hard work she put in was to gain access to money to pay for her children’s rising school fees and her family’s everyday needs. Yet, she never compromised on her own dignity and well-being. ‘I’ve never thought twice about quitting if the job gets too difficult for me to perform,’ she says. ‘I left one job because I was pregnant with my younger son and couldn’t work to the best of my ability. I left another job after my older son tragically died.’

One of her longest stints as a sweeper was at a school where she had enrolled her two surviving children after it became difficult for her to pay their exorbitant tuition fees. ‘The principal of the school gave me a discount on their school fees,’ Shehneila says. ‘She also ensured that my children weren’t made to feel inferior to the other students just because their mother was a sweeper at the school. The teachers and students, who were mostly Muslim, treated my children with respect and didn’t make them feel like outsiders.’

Shehneila stayed at the job until her daughter completed her intermediate education and she could finally afford to pay her son’s tuition fee at a non-discounted rate. ‘My daughter’s graduation was a proud moment for me,’ she recalls. ‘I felt I’d done my best to spare her from the fate I had been cursed with.’

Less than perfect

Shehneila’s current job at a private corporation came to her as a blessing in disguise at a time when the future seemed bleak. ‘I was working at a school until 2020 when the coronavirus started spreading all over the world,’ she reveals. ‘The school moved all its classes online and told me to stay at home. In the initial months, the school administration paid me my salary but later decided to sack me. I stayed home for two years and struggled to find a job as most people didn’t want to keep a part-time domestic cleaner in their homes for fear of coronavirus.’

During these difficult months, Shehneila’s husband—who now works as a sweeper at a local college and earns Rs23,000—became the sole breadwinner. However, his salary wasn’t sufficient to run their household as the prices of essential items hit a record high. Driven by the instinct to shield her family from poverty and hunger, Shehneila jumped at the first job she could find through a third-party contractor.

‘It’s not too bad,’ she admits. ‘I start work at 8:30 AM and clean the women’s toilets on all building floors at least three times a day. It’s a relief that people don’t leave the toilets too dirty after using them.’

Over the last few months, her initial sense of relief and contentment has gradually started to erode.

‘My job pays me Rs20,000,’ she says with a heavy sigh. Shehneila’s salary is below the minimum wage of Rs25,000, which was fixed in the budget for 2022/23. Over the last few months, efforts have been made by the relevant stakeholders to urge the government to raise the minimum wage. Yet, workers like Shehneila are likely to remain unaffected by these developments and continue to draw salaries that fall abysmally below the minimum wage.

‘It isn’t easy for me and my husband to feed our families with a collective salary of Rs43,000,’ she says, clicking her tongue in frustration. ‘One shouldn’t be nashukra [ungrateful], but so many of our day-to-day needs aren’t being met because we just don’t have the money.’

Shehneila doesn’t harbour any unrealistic expectations about the salary package she deserves. ‘I’m not demanding lakhs of rupees for the work I do,’ she clarifies. ‘I would like to get paid what I deserve. I’ve heard that cleaners who work for government departments get paid more than Rs25,000 for the same kind of work I do. Frankly, I’d be content with anything between Rs25,000 and Rs30,000.’

Shehneila isn’t wrong about the salary increments for sanitation workers who are affiliated with government-run departments. In January 2023, the Sindh High Court directed the Sindh government to pay sanitation workers in all its departments the legal minimum wage of Rs25,000. Unfortunately, Shehneila believes it is impossible for sanitation workers who work on a contractual basis to obtain increments. In fact, the mere prospect of asking her third-party contractor for a raise gives her goosebumps as her previous requests—like those of many other contractual workers—have been rebuffed.

‘My thekedar [third-party contractor] is very strict,’ she explains. ‘He says: ‘Yeh thekay ka kaam hai, ishi paisay main karo, warna na karo [this is contractual work. Either work for this salary or don’t work at all].’

Leave of absence

Apart from her financial woes, Shehneila struggles to obtain any non-wage benefits. She is entitled to a day off every week but finds it exceedingly tough to take any extra time off from her professional commitments. The concept of sick leave seems almost foreign to her as her thekedar doesn’t permit her the luxury of space to recover from any major or minor ailments.

‘I suffer from a thyroid condition that results in light periods,’ she explains. ‘On some days, it becomes difficult to work. Just this morning, I called my thekedar and told him it wouldn’t be possible for me to come to work. He said: “Aisay nahi chalega” [it can’t work like this]. I told him to send another cleaner in place of me, but he refused as most of his other cleaners were either occupied with other work or had taken unpaid leave for Easter. I had no choice but to go to work.’

The attitude adopted by Shehneila’s thekedar is not only sexist but also serves as a glaring example of how third-party contractors are not keen to help their workers in the event of a medical emergency.

It is equally difficult for her to convince the contractor to give her time off to celebrate any religious festivals. ‘At times, a generous employee at the company speaks to the thekedar and the manager on my behalf and gets me a day off for Holi. But we can’t always rely on these kind gestures,’ she says.

Casual leave is another ordeal that Shehneila and her colleagues have to reckon with. ‘Last month, my daughter got married and I needed a month off,’ she says. ‘My thekedar only allowed me to take leave if I agreed to bring a cleaner who could replace me for the duration of my leave. I agreed to his request because I needed time to prepare for my daughter’s wedding. The arrangement didn’t suit me as the thekedar paid the other cleaner for working last month. Believe me, I don’t have any money in my pocket at the moment.’

Nor did the thekedar allow her to take an advance for her daughter’s wedding. Fortunately, the bulk of the wedding expenses were borne by some generous relatives. ‘My brother-in-law, who is an electrician, helped me arrange the venue,’ she says. ‘Another family member helped us pay for my daughter’s chaandi [silver] jewellery. I was able to pay only for the food at the reception as I had received money from a committee pool. Overall, we managed to get her married with the support of our family.’

Pick-and-drop

Every day, Shehneila arrives at the office at 8:30 AM. ‘I’m one of the fortunate few as my husband drops me to work and picks me up,’ she says. ‘The other cleaners don’t have that privilege and have to travel long distances to get to work. Most of their salaries are spent on their kiraya [travel expenses].’

Shehneila’s husband recognises these challenges and doesn’t want her to spend too much of her salary on commuting to and from work, especially with skyrocketing fuel prices.

‘My husband gets done from work at 3:30 PM,’ she says. ‘But he waits at the college until 5:30 PM when I get done.’

No place to call home

Shehneila lives in a tiny apartment near Light House Market, Saddar, that she rents from a landlord who belongs to the Bohra community.

‘We pay him Rs15,000 in rent,’ she reveals. ‘We’re lucky we found this place as we have access to water and electricity. The gas supply isn’t as regular as we’d like, but we have no other complaints.’

Shehneila claims that her landlord ‘only rents his apartment to Hindus’, which serves as a much-needed safeguard from the threat of eviction she has encountered at the hands of previous landlords.

Also Read

A living hell : 'We have changed names, faces and dresses yet nothing has changed for us'

Her family’s housing dilemma began over a decade ago when they were asked to vacate the small quarters they lived in near the DJ Science College in Karachi. Shehneila’s family had lived here through the traditional but legally unrecognised pagri system. Under this arrangement, a landlord permits a tenant to use the property for a prolonged duration after receiving an amount that is below the market price. The tenant, in turn, pays a nominal monthly rent and cannot be evicted, even though the property remains in the landlord’s name and he continues to pay taxes on it.

‘We had no choice in the matter and started looking for a new place to live,’ Shehneila says. ‘This proved to be difficult as most landlords didn’t want a Hindu family on their property.’

Some of the landlords she came across put forward unusual conditions that made her feel increasingly insecure. ‘One of my previous landlords expected me to convert to Islam in order to lease his property,’ she says, still horrified at the memory of this conditional kindness.

Holiday season

A fresh fear lodges itself into Shehneila’s heart whenever the religious holidays are around the corner.

‘Nowadays, we barely have extra money to spend on new clothes for Diwali and other holidays,’ she says. ‘Thankfully, my children have always understood these matters. The only thing my son wants is to light fireworks on Diwali. I’m too scared to let them light fireworks as most of my neighbours are Muslim, so I usually send him to my mother’s house in Keamari. Over there, Hindus visit the mandir and celebrate the festival without any restrictions.’

Shehneila’s fear of celebrating her religious holidays has its roots in an incident that occurred a few years ago. Back then, she was living in a small flat in Pakistan Chowk and wanted to prepare gur ki roti [jaggery bread] for one of her religious festivals.

‘I didn’t want to make the rotiyan indoors as smoke would have spread through the entire house,’ she explains. ‘I went outside, set up a makeshift choola [stove] and began preparing the rotiyan. Within minutes, my neighbours had gathered around me and accused me of practising black magic. They were convinced I was a witch.’

Troubled by their aggressive reaction to a seemingly innocuous act, Shehneila left the neighbourhood the very same night. ‘My family’s safety always comes first,’ she adds.

A tenuous freedom

Apart from these occasional threats to her family’s safety, Shehneila complains of no other form of discrimination.

‘I live here with complete independence,’ she declares proudly. ‘My children celebrate Independence Day with greater enthusiasm than our own religious holidays. They would even die for their country.’

These words are spoken with sincere patriotic feelings but also reflect a survival instinct that has been learnt and sharpened over time.

‘I do wish the government did more for Hindu sanitation workers as well as the entire Hindu community,’ she admits. ‘My husband and I have cleaned toilets and swept floors just to ensure that our children gain an education. I wouldn’t want my children and grandchildren to follow the same path as me. I hope the government can do something to help Hindu children gain an education so they too can find better opportunities.’

* Name changed to protect identity.

Published on 19 Aug 2023