Muhammad Naeem Zafar, a farmer from Bhakkar district of western Punjab, has cultivated chickpeas and moong pulses on 20 acres of land for years. In 2021-22, however, he chose to plant these crops on only 10 acres of land. He took this decision because moong crop had not generated enough income for him in 2020-2021.

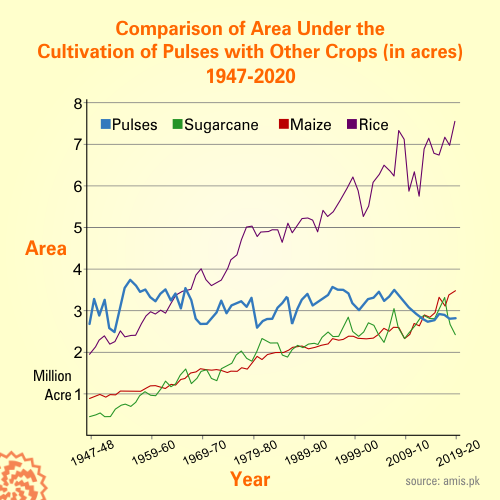

Farmers across Pakistan are similarly reducing the land they allocate for growing pulses. A joint study by experts of Pakistan Agriculture Research Council, University of Western Australia and the Australian National University confirms this change. It says the area under the cultivation of pulses in Pakistan decreased by 1.3 percent every year between 2014 and 2017. Domestic production of pulses declined by 6.2 percent in the same period.

The Economic Survey of Pakistan also confirms these numbers. It states that the chickpea crop in 2019-20 was planted on 2.36 million acres but, in 2020-21, the area under its cultivation decreased by 8 percent and its production decreased by 48 percent. The area under the cultivation of masoor and mash also decreased by 32 percent and 20 percent, respectively.

These facts are also validated by the Punjab government's Crop Reporting Service which keeps a record of the area under the cultivation of various crops as well as of their production. Its data shows that the area under the cultivation of mash in Kharif (autumn) of 2020-21 was 11,669 acres which decreased to only 4,200 acres in 2021-22. In fact, the area under the cultivation of all the pulses, except moong, decreased in 2021-22 by 46 percent.

Ahmed Faraz, a farmer of Balkasar village in Chakwal district of northern Punjab, confirms this trend. He says farmers in his area who used to cultivate pulses such as masoor, mash and moong a few years ago now prefer to grow oilseeds such as mustard, rye, taramira and canola as well as wheat because “these crops are more profitable”. The Punjab government also provides financial assistance of 5,000 rupees per acre for the cultivation of oilseeds which serves as an incentive for their cultivation, he says.

Stable prices, prosperous farmers

Nationmaster, a private website that compiles and publishes statistics on agriculture and other food items, says that Pakistan consumed 1.36 billion kilograms (1,367,000 metric tons) of pulses in 2017. In other words, every Pakistani ate about 6.25 kilograms of pulses that year.

To meet this demand, pulses worth 266.8 million rupees are being imported every day. According to the data compiled by Nationmaster, the quantity of pulses imported from other countries increased by an average of 24.3 percent every year between 2017 and 2021.

It is worth mentioning here that Pakistan was exporting chickpeas and other pulses till 2008. When, however, the world market experienced a shortage of these grains in 2007, the Pakistani government imposed a 35 percent export tax on them to discourage their export and ensure their availability within the country. While the imposition of this tax helped to stop the export of pulses, it also led to a constant increase in their imports.

Dr Kashif Rasheed, a former senior scientist at the Ayub Agricultural Plus Research Institute in Faisalabad, blames the importers of pulse for this state of affairs. These traders, according to him, “create an artificial gap between supply and demand and raise or lower the prices as they please”. In his view, the prices are reduced usually “when the local crop begins to enter the market”. As a result, local farmers are not able to get a good price for the pulses they produce which discourages them and, hence, they reduce their cultivation.

Rasheed argues that prices of pulses in the local market will become stable if their import is restricted. This, he says, will benefit Pakistani farmers and they will be incentivized to cultivate more pulses. To cite an example of this, he explains how, as a result of an increase in the price of moong in the world market two years ago, locally grown moong was sold at 200-250 rupees per kilogram.

Local farmers, however, drew wrong conclusions from this rise and planted far more moong than before in 2020-21. This resulted in its production exceeding its demand so its price was reduced to only 80 rupees per subsequently.

Yielding losses

Pulses are considered to be a part of small crops in Pakistan, grown mostly in arid zones where farmers depend on rain water for cultivation. Their four main varieties, chickpeas, masoor, moong and mash are cultivated in two different seasons called Rabi (spring) and Kharif (autumn).

Chickpeas and mash are grown in Rabi season along with main crops like wheat and maize. Both these pulses are mostly grown in Thal desert in western Punjab and in the rainfed areas of northern Punjab. In fact, more than 85 percent of the total land used for the cultivation of chickpeas in the country is located in five districts of Thal — Bhakkar, Khushab, Jhang, Layyah and Mianwali.

Moong and mash are grown in Kharif season in which important crops such as cotton, rice, sugarcane and maize are also grown. These pulses are grown in lands that can retain water. Consequently, 50 percent of moong is grown in only one district, Bhakkar, while 34 percent of it is grown in Layyah and Mianwali districts. The largest area of land under the cultivation of mash is in Narowal, Sialkot and Rawalpindi districts while the major portion of masoor is sown in Rawalpindi and Chakwal districts.

According to the government data, pulses are grown on more than 3 million acres of land in Pakistan every year, out of which chickpeas are planted on more than 2.1 million acres of land. This makes Pakistan the 16th largest producer of pulses but it ranks 161 in terms of their yield per acre.

Even within Pakistan, the yield of pulses is much less than that of other crops. For example, per acre yield of wheat has increased by 243 percent since 1947 and that of sugarcane, rice and maize has increased by 134 percent, 174 percent and 478 percent, respectively. But, on the other hand, the yield of all pulses, except moong, has increased nominally. The yield of moong has also increased by only 67 percent in the last 74 years – from 180 kilogram per acre to 300 kilograms per acre.

According to farmer Zafar, the main reason for this difference in the yield of other crops and pulses is that the latter are usually grown in areas where canal or groundwater is not available for irrigation. Talking about the exceptional case of moong, he says that the recent increase in yield became possible because its cultivation has shifted from Thal to areas where canal water is available for irrigation.

The data released by Crop Reporting Service validates his claims. It says moong was cultivated only on 1200 acres in Sahiwal division during 2019-20 but, the following year, the area under its cultivation reached 13,294 acres. In the same period, the area under moong cultivation in Multan division increased from 2,332 acres to 31,000 acres and in Bahawalpur division from 5,000 acres to 14,000 acres.

Also Read

Phalia Sugar Mill: How its workers are paying the price for its financial and environmental impropriety

The average per acre yield of moong in these irrigated areas has been recorded at 360 kilograms whereas the yield in rainfed areas has never been more than 120 kilograms per acre.

Apart from water scarcity, the main reason for the low yield of pulses is that the government extension services in agriculture ignore pulses while advising farmers on what crop to sow and what to avoid, says Faraz, the farmer from Chakwal. To prove his point, he highlights the fact that the government research institutes have neither prepared any new seed for increasing the production of pulses nor have they imported better seeds from abroad.

He also says that modern machinery and other technologies are available in Pakistan to help the cultivation of wheat, maize and oilseeds but, "pulse growers do not have access to similar facilities”. This is why farmers have to rely solely on the help of labourers for the cultivation of pulses. “Firstly, it is very hard to find a labourer to help with the cultivation and even when we find one, the compensaton for his services increases our cost,” Faraz says.

As a result, growing pulses has become unviable for most farmers.

Published on 28 Feb 2022