Indus river system is bracing for a new storm. It is, however, not expected to flood low lying riverine areas. This time around it is threatening to flood foundations of our federation.

Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif appointed a retired BPS 22 officer of federal government, Zafar Mehmood, as chairman of Indus River System Authority (IRSA) on March 12, 2024. He did so in exercise of powers vested in his office by an ordinance promulgated by the caretaker government on February 14 – just days before the end of its extended tenure.

The ordinance is a brazen attempt to bypass the parliament to redefine the entire system to manage rivers of Pakistan that are shared by its four federating units – the provinces. Former President Arif Alvi thought that such a major move shall not be made without following a democratic legislative process and refused to give his assent to it. The ordinance anyway was promulgated ten days after his refusal, as provided in Article 89 of the Constitution.

Appointment of the IRSA chairman under the ordinance infuriated Pakistan People’s Party, the major ally of ruling Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz in Islamabad. Naveed Qamar, PPP MNA, made no bones in condemning the PM’s decision on the floor of National Assembly and Sindh government also wasted no time in voicing its disagreement. The Prime Minister withdrew his order within less than 48 hours.

The Prime Minister, however, still has all the powers that the ordinance has arbitrarily vested in him till the expiry of its constitutional life of 120 days which may get two extensions of the same period through resolutions passed by the National assembly. After that, the ordinance will be treated as a bill that has to pass through the regular democratic legislative process to become a permanent law.

The government may, however, withdraw the ordinance at any time or may decide to let it lapse and not table it in the parliament.

There is no information available about the future plans of the ruling party. The prime minister’s hasty use of his new-found power (to appoint the chairman), however, is being read as a worrying sign by the critics of this piece of temporary legislation. Their suspicion is supported by a similar action taken by Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz in July 1998 when the party enjoyed two-third majority in National Assembly and had its governments in all four provinces and yet had taken the short route of promulgating an ordinance to influence IRSA Act 1992. That ordinance was withdrawn too - in less than three months.

The current ordinance, however, was brought by the caretaker setup that ruled the country on a weak constitutional ground. It obviously could not take such a step without the support of its not-so-secret sponsors, if it had not actually acted on their behalf.

In that sense, the ordinance does offer a glimpse into the mind of our establishment – about how they want our rivers to be managed, water apportioned and disputes resolved or suppressed.

With this background, Lok Sujag has done a comparative analysis of the original IRSA Act 1992 and the IRSA Ordinance 2024 – with the purpose of aiding an informed debate on the matter.

Here are its main features:

All hail to the appointed chairman

To start with, the ordinance attempts to totally exclude the central stakeholders in our river system – the provinces – from the decision making processes of the Authority.

Indus River System Act 1992 provided for the formation of a five member body – one member each nominated by the four provincial governments and one by the federal government. The office of the Chairman, with one year tenure, rotated among the five members following a prescribed pattern. This arrangement was aimed at equally distributing the ownership of the Authority among all members.

The 2024 ordinance has struck down this clause. No more one-year chairmanship for any province. It unequivocally proclaims: “The Authority shall comprise of a Chairman and five members … The Chairman shall be an employee of the Federal Government, either serving or retired in BPS-21 or equivalent or above, to be appointed by the Prime Minister.”

Unlike the ordinance, the chairman will no more be a member of the body but a separate office to be filled by a bureaucrat – civil or military. The ordinance does not specify the chairman’s tenure but it does declare the chairman eligible for re-appointment for one or more terms as the prime minister may desire.

After making the center-appointed bureaucrat the head of the authority, the ordinance has relocated the federal and democratic spirit embodied in the IRSA Act 1992 into a new office – the Vice Chairman. This office will now rotate among provinces on the manner the 1992 Act had prescribed for the office of the chairman.

However, the ordinance has ensured that the new office of Vice Chairman remains without any power!

There is no section in the ordinance defining its functions, powers or duties except one saying that he can preside over the Authority’s meeting in absence of the Chairman.

Independent and not-so-independent experts

The ordinance has redefined functions and powers of the Authority and has assigned all of them to a newly introduced body - Independent Experts Committee. The eight members of the Committee with each having at least ten years’ experience in water related engineering fields will be appointed by the Chairman who will also decide the head of this committee.

This committee will be eyes, ears and arms of the IRSA Chairman. It will aid, assist and advise only the Chairman and work under his directions to ‘carry out all matters connected therewith and ancillary thereto’.

The members of the Authority will have no role in appointment and working of this committee.

Incidentally, IRSA Act 1992 had provided that the five members appointed by the federal and the provincial governments shall be ‘from amongst high-ranking engineers in irrigation or related engineering fields’.

Experts they might be but probably the architects of the ordinance do not find them ‘independent enough’ to work under the prime minister’s hand-picked chairman.

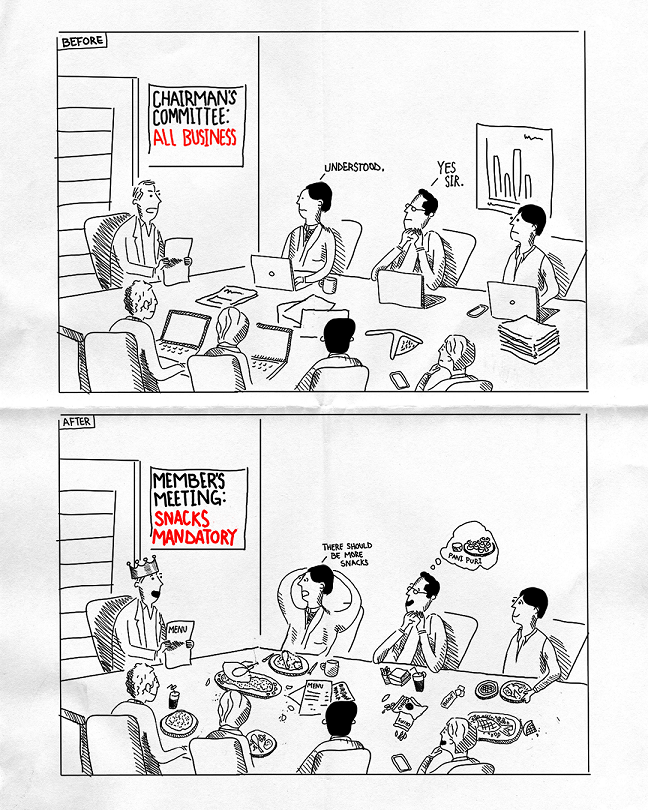

The Chairman and his ‘independent’ experts will run the show at IRSA, while the ‘not-so-independent’ experts/members may continue to gather for their mandatory monthly meetings. One can only hope that they will be served snacks during their meetings at the IRSA office!

Graphic by Hamza Saqib

Drowning out 30 years of gains

IRSA Act 1992 had empowered the Authority to ‘lay down the basis for the regulation and distribution of surface waters amongst the provinces according to the allocations and policies spelt out in the Water Accord’ (Sub-section 8 (a)). The accord refers to the agreement – Apportionment of the Waters of the Indus River System between the Provinces – signed by the provinces on March 16, 1991 and approved by the Council of Common Interests (CCI) five days later.

The agreement had clearly defined shares of provinces based on their land usage, agricultural needs and past data of water usage. The same Accord had actually conceived the creation of Indus River System Authority with ‘representation from all the four provinces’ as its implementing body. IRSA thus has over thirty years of history of consensus building among the provinces over the vital matter of sharing waters.

Ordinance 2024 aims to bulldoze that history by adding an ‘Explanation’ to sub-section 8 of IRSA Act 1992: ‘technical basis for the regulation and distribution of surface waters shall be determined by the Independent Experts Committee.’

The ordinance has also added sub-section 8(ea) that actually converts all the provincial irrigation departments into subordinate implementers of IRSA. It adds to the powers and duties of the Authority:

‘(ea) issue binding directives, with regards to powers envisioned under this Act, to Federal entities, including, inter alia, Water and Power Development Authority, as well as each of the Provinces, which shall implement the same at, inter alia, the Water Regulation Point(s). In case of failure or inordinate delay, by any entity or person, in implementing the directives issued under this Act, the Authority shall have the power to impose such penalties, as may be prescribed;’

But how can the Chairman and his committee exercise their unlimited powers if the provinces continue to be in charge of the data of river and canal discharges?

The ordinance has not been oblivious of this vital aspect.

Controlling data is controlling water

IRSA Act 1992 clearly stated as Explanation under Section 8(c): ‘Actual observation and compilation of the data [related to water flows] shall be the responsibility of the respective provinces, Water and Power Development Authority and other allied organizations, while the process shall be monitored by the Authority’.

Ordinance 2024 has omitted this explanation.

It has instead added a sub-section 8(ba) that authorizes IRSA to ‘monitor and compile through telemetry or other modern technological means, the river and canal discharges of all Water Regulation Points being observed by Provincial Irrigation Departments and WAPDA, and conduct, from time to time, water audit thereof.”

Also Read

Sindh's objection over Greater Thal Canal: 'Construction of a new canal in Thal will reduce our share of water even more'.

The ordinance has introduced the term – Water Regulation Point – which was not part of IRSA Act 1992 and defined it as: gauge and discharge locations … including but not limited to water storage, dams, run-of-river hydropower projects, barrages/headworks, canal head regulators, escape structures, outfall structures, tails of inter-river link canals.

The Ordinance has also clearly spelled out that if there is a conflict between observations made by the Authority and any provincial irrigation department or WAPDA ‘observations of the Authority shall take precedence over all observations to the contrary.’

The ordinance also gives powers to IRSA to proceed against persons and entities involved in water theft and tempering of installations [to collect water discharge data] and data.

But how will the Authority establish its monopoly over the data?

That’s also covered in the Ordinance 2024.

It aims to insert into IRSA Act 1992, Section 10B that defines the measurement business as one of the functions of Independent Experts Committee: ‘4(b) advise [the Chairman] on the monitoring, handling and compilation of the data received through telemetry or other modem technological systems, of all Water Regulation Points;’

So the Authority, as perceived in the Ordinance, will collect data from all and every possible point in the Indus river system spread over the four provinces and only its data will be considered true. So if a province could dare to differ, the Chairman and his cohort of independent experts will play both the judge and the jury.

And it doesn’t stop there. The role of appellate court is also going to the Chairman!

The judge, the jury and the appellate court

IRSA Act 1992 had spelled out dispute resolution process in its section 8(2) which reads: Any question in respect of implementation of Water Accord shall be settled by the Authority by votes of the majority of members and in case of an equality of votes, the Chairman shall have a casting vote’ and Section 8(3): ‘A Provincial Government or the Water and Power Development Authority may, if aggrieved by any decision of the Authority, make a reference to the Council of Common Interests.’

Since the Chairman under the Ordinance 2024 is not a member of the Authority, his casting vote has been withdrawn. Instead, if there is disagreement among the members, they have to ‘file a review before the Chairman who shall decide the matter ‘through a speaking order’, after consultation with the Independent Experts Committee and/or such independent experts or consultants, as may be deemed appropriate by the Chairman’ and orders passed by the Chairman ‘shall be final and shall not be called in question before any Court, forum or authority, except the Council of Common Interests.’

The CCI shall, according to the Constitution, meet at least once in ninety days. But the same has not been the practice. The CCI had met twice in 2020, five times in 2021 and only once in each of the next two years.

In May 2022, Sindh High Court accepted a petition against IRSA regarding water crisis in the province. But this will not be possible under the ordinance.

The ordinance not only seats the Chairman at a position of power in disputes over water, it also attempts to make access to other avenues more difficult.

Diving into strategic depths of Indus river system

The handing over of total control over the entire country’s river system to the Authority is bound to face resistance from the existing stakeholders at provincial and local levels. Probably to address the impending challenges, the Ordinance has bestowed the Authority with some special powers.

It has added another sub-section to the powers and duties of the Authority which says that it may ‘through majority vote declare a location or installation to be of strategic importance’ and to safeguard these strategic locations ‘the chairman may request the Federal Government to provide requisite assistance through the Armed Forces of Pakistan, or other law enforcement agencies, as may (be) required, from time to time.’

So if three of the five members of the Authority, say the federal government and two provinces, agree to declare a location in any of the other two provinces as strategic, the Chairman can call army to safeguard it – against local resistance. This militarization of water disputes can prove to be extremely dangerous for the federation of Pakistan.

There are two more new powers given to IRSA that could turn this body from a dispute resolution forum to an instigator and initiator of ‘water wars’.

One authorizes it to ‘contract, engage, collaborate, transact, and enter into commercial arrangements with governmental as well as corporate entities, for carrying out the purposes of this Act’ and two it can ‘impose, vary and recover fees, charges, cess, or other sums, from time to time, as may be prescribed;’

Graphic by Hamza Saqib

These two powers combined can potentially convert the Authority from a regulator and monitor to a corporate body selling river waters to governmental as well as corporate entities. And if such corporate entities are bringing in the much needed foreign investment, they can be declared as strategic.

Published on 22 Mar 2024