It’s 12:45pm. *Iqbal and his companions begin to gather under the shadow of an old water tank. The ground beneath them has become muddy after yesterday’s rain.

The group of 15 sanitary workers is dressed in worn out, ragged clothes. Toenails of some of them are caked up with black sludge from sewers. Their morning shift ended at 10am and they are now waiting for their supervisor who would mark attendance for their second shift and assign them duties.

Tiredness is writ large on their faces as if they had just returned from a long, exhausting journey but they have to be ready for the next shift starting at 1pm.

The group is responsible for keeping the streets and open drains in Union Council 60 of Sheikhupura city clean, ensuring that sewers run 24/7. All of them are Christian daily wagers.

Though some of them have served for over 20 years, they are still deprived of job security, pension, allowances, gratuity or compensation for death on duty.

Extra financial burden of buying tools

Iqbal, 47, is the longest-serving daily-wager in the group. He has been working with the Tehsil Municipal Corporation (TMC) since 2001—a journey of 23 years. He earns Rs32,000 for 26 days of work. If he takes a day off due to an emergency or family engagement, he loses his daily wage.

“Earlier, I could manage to save some money when inflation wasn’t this bad but now it’s impossible,” Iqbal laments.

Pointing to his co-workers as they respond to the supervisor’s roll call, he adds, “All of them are in heavy debt stress. I owe about Rs0.7m debt, with around Rs0.5 to be paid to a bank. They deduct Rs13,000 from my monthly wage of Rs32,000.”

Iqbal says that the government has announced a minimum wage of Rs37,000 but he and his colleagues haven’t received any raise yet.

The financial situation of the workers gets worse when they are required to buy their own tools for sweeping, cleaning and waste disposal. They also have to cover the cost of repairing damaged equipment on their own, which adds to the financial strain.

Asif, 27, a father of two, who has been working on a daily wage for 10 years, was asked by his supervisor to bring his own tool if he wanted to work. He purchased a wheelbarrow for Rs40,000 that he borrowed from friends.

As he fills his cart with sewer sludge that had solidified after drying for days on the edge of a narrow street, Asif responds as to why he did not demand the tool from the department. “I am a daily-wager, not a permanent worker. I cannot make any demands”.

Speaking to Lok Sujag about the workers buying their own equipment, Additional Deputy Commissioner Muhammad Jamil categorically denies the allegations, stating, “I have not received any such complaint in my municipal corporation. No sanitary worker has made any complaint to me about the lack of equipment. If someone had approached me, I would surely have taken action.”

The hanging sword of job insecurity

The daily wagers like Iqbal, Asif and their co-workers not only have to makes ends meet in their limited resources but they live with the constant fear of getting fired any day at the whims of their bosses–a fear that keeps them trapped between the threat of unemployment and the unavoidable choice of working under extremely adverse conditions.

“I was targeted by the Tehsil Municipal Officer (TMO) just for discussing with friends the possibility of filing a petition before the court,” Shakeel, a senior colleague of Iqbal, recalls.

“He suspended me when I was a daily-wager. Left with no remedial measure, I had to seek help from a friend who worked in the chief minister’s office to get reinstated. Others are not that lucky,” he adds, feeling sorry for some of his colleagues who had lost their jobs.

Shakeel was part of the group of 31 daily-wage sanitary workers who fought a successful legal battle from 2013 to 2018 against the local government that oversees the municipal corporations in Punjab, and secured ‘permanent employee status’ for themselves.

Daily wage, a permanent trap protected by govt

In Sheikhupura city, the municipal corporation, (MC) which works under the Local Government and Communities Department, serves as the regulatory body for sanitary workers.

It is responsible for their recruitment, termination, service status and provision of equipment. The city has a population of 591,424 living in 89,070 households.

There are 310 workers (175 daily wagers and 135 permanent employees) who perform sanitation duties. This means each worker is responsible for the sanitation needs of approximately 287 households.

Shahzad, former president of the ‘Jafakash Mazdoor Union’ (JMU) and a second-generation sanitary worker with the municipal corporation of Sheikhupura, points out, “We are about 130 workers short as the amount of work as well as the population have doubled.”

This workforce shortage puts immense pressure on the existing workers. Despite their need to keep the city clean, the Punjab government is not giving the daily-wagers permanent employment.

A 2021 notification by the Services and General Administration Department of the Punjab government says that “a large number of such (daily wage) employees have been working for indefinite time spans stretching over years.”

It further instructs hiring authorities to relieve daily wagers after 90 days, warning that failure to comply will result in disciplinary action against those responsible.

This indicates that the notification itself recognises the unlawfulness of retaining daily wagers beyond the legal limit of 90 days, except in cases of extreme emergency—a condition that clearly does not apply to the continuous and essential nature of sanitary work.

For the state–specifically its third tier, the local government–it is perhaps a way to minimise the financial burden on the national exchequer while extracting the maximum labour from the workers. But for the daily-wage labourers, it means years of labour with the minimum wage, with no future benefits or job security in sight.

“The daily wagers’ existence is invisible. Nobody cares even if they die. They won’t receive any compensation,” Shahzad remarks.

“As regular staff, you earn more than a daily-wager who has served for the same duration. And there are no retirement benefits.”

The local government employed a strategy to keep daily wagers trapped in a cycle of continuous labour by issuing new orders every 89 days.

Shazad explains that this practice persisted because, after 90 days, the authorities would be required either to offer a formal contract or terminate their employment. Shahzad adds that this practice of issuing new orders after 89 days continued only until 2016.

After that not only did they not hire any new workers, leading to a massive workforce shortage, they didn’t even bother to issue new orders.

‘Permanent workman’ or ‘permanent employee’--- the legal quagmire

Sajawal, a colleague of Shahzad, along with 149 other sanitary workers from TMC Sheikhupura, filed a writ petition before the Lahore High Court (LHC) in 2022 to have their services regularised and obtain due back benefits.

The grievances detailed in this petition are shared by sanitary workers across Punjab. Following Sajawal’s case, over 20 similar petitions were filed before the LHC.

The petition made the chief officer (CO) Municipal Corporation Sheikhupura and secretary Local Government and Community Development, Lahore respondents as they had kept workers in the status of daily wagers for years.

“Many of the 150 workers who have filed the petition have already retired as daily wagers, some after serving for more than 20 years. None of us want our children to be part of this work anymore.” Shahzad declares.

In response to the petition, the high court ordered the chief officer of the Municipal Corporation Sheikhupura to decide the issue “in accordance with the law after providing an opportunity of hearing to all the stakeholders”.

The chief officer (CO) issued an order on Oct 10, 2022, declaring the petitioners and other sanitary workers as ‘permanent workmen’ instead of ‘permanent employees’.

This distinction is significant because ‘permanent workmen’ do not receive pension, gratuity, and other benefits that ‘permanent employees’ are entitled to.

Unsatisfied with this outcome, the workers filed another petition challenging the order, arguing that it had no legal effect and was not applicable to the case of the petitioner.

The CO’s order based its reasoning on a 2013 Supreme Court judgement, which states that the service of a daily-wage employee should be governed by the Industrial Commercial Employment (Standing Orders) Ordinance of 1968, and that such an employee should be considered a permanent workman if they have been performing their duties continuously for more than nine months.

However, the workers’ counsel, Mudasir Farooq, explains the 1968 ordinance applies only to commercial establishments and that the local government is not a commercial entity.

It is the third tier of the state and is responsible for development works in districts and municipal committees, including sewerage, drainage, and soling. Hence, it cannot be classified as a commercial establishment, making the application of the 1968 ordinance to sanitary workers unlawful.

He further explains that the 2013 Supreme Court judgement used by the local government to justify its act was meant for an employee hired by a contractor of the works department.

In contrast, in this case, the petitioner and other workers were employed by the local government, not for a specific construction job, but for a role that is inherently permanent in nature.

“The appropriate legal framework governing the service structure of daily-wage workers is The Punjab Local Council Servants (Services) Rules, 1997. According to these rules, the workers should be regularised as ‘permanent employees,’ which would entitle them to full benefits, including pension and gratuity.

However, the CO office disregarded these rules and based its decision on a Supreme Court judgement that they have misinterpreted,” says Farooq.

Same workers, different laws

The Municipal Corporation Sheikhupura has already lost a similar case in 2018. Shakeel, who was regularised as a result of that case, recounts how he and 30 other colleagues filed a writ in the labour court, which they won.

The department appealed to the Labour Appellate Tribunal, which upheld the court’s decision but noted that the department claimed a lack of financial resources to pay back benefits.

The municipal corporation then took the case to the high court, which also ruled in favour of the workers.

This history highlights a troubling pattern of legal battles where, despite clear rulings in favour of workers, the department continues to resist compliance and exploit legal loopholes to avoid granting rightful benefits to the workers.

The office of the chief officer municipal corporation had previously regularised 28 sanitary workers through an office order dated Jan 13, 2018, and nine Baildars through a notification dated May 5, 2019.

These orders demonstrate that the regularisation was based on the Punjab Local Council Servants (Services) Rules, 1997.

The question arises as to why the same office issued a different order for Sajawal and 149 other daily-wage sanitary workers compared to the workers in the aforementioned cases and insists on dealing with the petitioners under the Industrial Commercial Employment (Standing Orders) Ordinance 1968.

“Isn’t it a case of unreasonable classification of similarly placed persons engaged on a daily-wage basis in the local government, given that the department had previously regularised many workers as permanent employees using the Punjab Local Council Servants (Services) Rules 1997?” the lawyer asks.

He also believes that the municipal corporation of Sheikhupura is applying two different sets of rules to workers of the same category, which amounts to discriminatory treatment.

Also Read

Stigma and sacrifice: A sanitation worker’s quiet battle for dignity and education in Karachi

During the concluding arguments on June 12, 2024, the assistant advocate general of Punjab announced that the government intended to withdraw all instructions and controversial notices related to the service status of daily-wage workers, including declaring them as “permanent workmen”.

The maze of clueless officialdom

When Lok Sujag reached out to the office of the secretary local government for his version on Aug 27 as no further notification had been issued by that time, it emerged that no one there knew who was handling or overseeing the issues related to the sanitary workers in Punjab.

This reflects a serious lack of professionalism and clarity in the department responsible for managing thousands of workers.

The secretary of the local government was a party to the case in the petition. Instead of providing an official statement or directing Lok Sujag to the relevant authorities under his purview, the secretary redirected it to the Lahore Waste Management Company (LWMC)--an organisation with no involvement in the municipal workers employed under municipal corporations across Punjab.

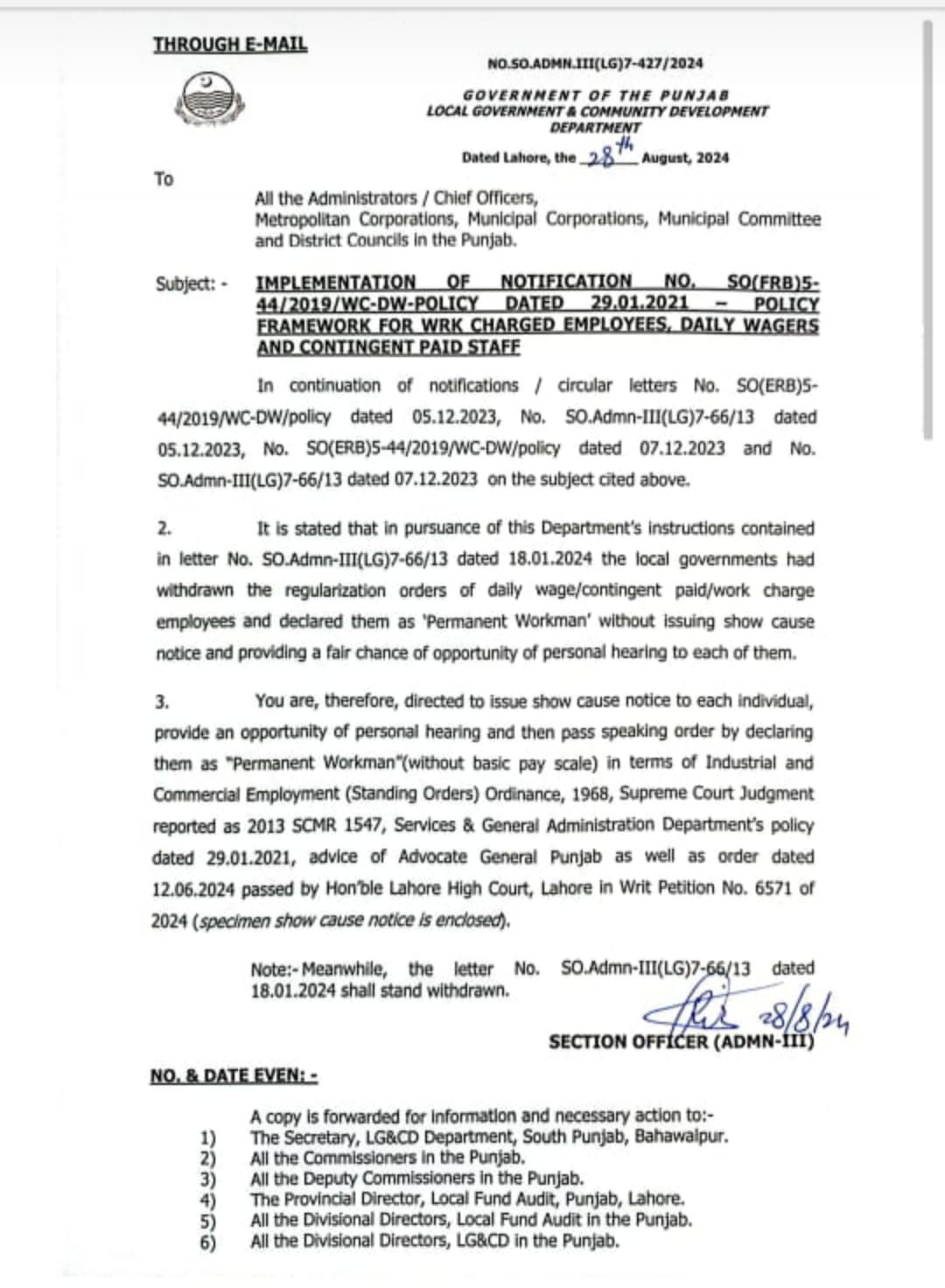

However, on Aug 28, 2024, the Local Government and Community Development Department directed all metropolitan and municipal corporations, committees, and district councils in Punjab to issue show-cause notices to all daily wagers employed by these bodies.

The directive required all these bodies to provide an opportunity for personal hearing and to pass orders declaring the workers as “permanent workmen”--a status that still lacks the basic pay scale and associated benefits.

*All the names of the characters in this story are fictitious.

Published on 7 Sep 2024