Lawyer Abdul Wasiq’s 18-year-old sister Mehek tested positive for coronavirus on 22nd December 2020.

Two days later, a government official turned up at their Harley Street home in Rawalpindi city. She introduced herself as a ‘supervisor’ and told Wasiq and his family that they all needed to be tested for corona virus. When he asked her if she would collect blood samples or nasal swabs for the test, she did not know.

The ‘supervisor’ left without taking any samples.

Another government team visited their home on 26th December. It listed down the names and other personal details of all the family members – including the numbers of their identity cards and mobile phones. But it, too, did not collect any samples.

Five days later, Wasiq and everyone else in his family received their reports through text messages. Issued by the Punjab Primary and Secondary Healthcare Department, these reports declared all of them to be free of corona virus – but without being tested at all.

Wasiq’s sister, in the meanwhile, died due to corona-related complications.

Rabiba Bano had a similar experience.

In November 2020, officials of the Punjab Primary and Secondary Healthcare Department informed her that her entire household needed to be tested for corona virus because her brother-in-law was found to be infected by it. A government team came to her house in Lahore’s Johar Town area on 20th November and collected samples of all her family members.

Seven days later, when she received no test results, Rabiba contacted the department and was informed that their samples had been misplaced. “It turned out that they had not labeled the samples and put all of them together,” she says.

She immediately complained to every official that she could find.

A day later, an official showed up at her house and collected the samples again. Twelve hours later, she received the test report of only one sample. More than three months have passed since then but other test reports are still awaited.

Rabiba’s is a middle-class family with six members. They cannot afford to spend around 40,000 rupees that corona testing at a private laboratory will cost them collectively. “We could do nothing except wait for the government to tell us if any of us was corona positive,” she says.

There may be hundreds of thousands of similar families across Pakistan who could not get themselves tested for corona virus because of either the government’s mismanagement or due to the prohibitive cost of private testing.

Corona testing in Pakistan remains a lackluster affair and this is obvious from the government’s own data.

Syed Tajamul Hussain, the chief executive of Love for Data, a company that helps the government maintain corona-related data, believes the high cost of tests is one of the major reasons why people do not get themselves tested for the virus. “Even if they have the symptoms, they stay at home and wait for the virus to run its course,” he says.

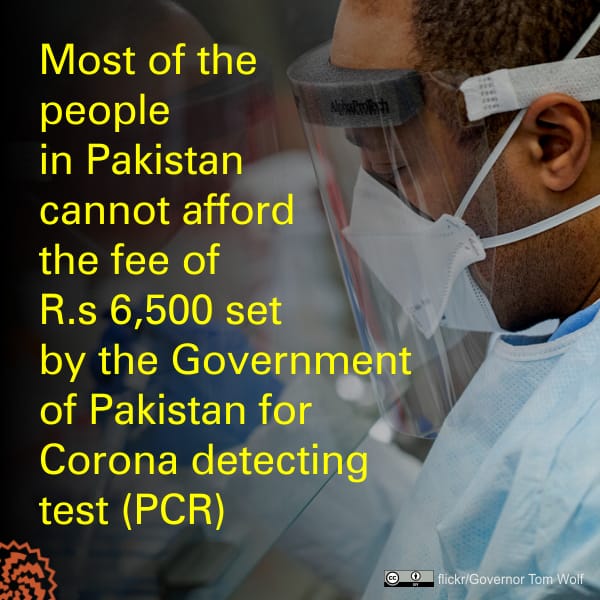

Initially, the prices of private testing also varied from one laboratory to another. In the first wave of the corona pandemic in Pakistan between March and July 2020, the price of a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test to detect corona virus ranged between 5000 rupees and 11,000 rupees. In September 2020, however, the government fixed the rate at 6,500 rupees.

This price, too, is beyond the financial budget of most people living in Pakistan. Even middle class families – comprising of six to seven members each and with a monthly income of 100,000 rupees -- could not afford to spend about 40,000 rupees to have all their members tested privately.

The numbers speak

At the start of the pandemic, Pakistan had the capacity to perform only 200 tests per day. This capacity was later increased with the help of international organizations – such as the World Health Organization (WHO) – first to 30,000 tests per day and later to 50,000 tests a day.

This capacity, though, has not been utilized to the full even once. Daily testing reached closest to it on 27th November 2020 when 48,223 tests were conducted across Pakistan. The second highest number of tests was achieved on 18th December 2020 when 48,078 tests were conducted throughout the country.

Corona testing in Pakistan, indeed, remains a lackluster affair – and this is obvious from the government’s own data.

The total number of corona tests done in the country stood at 8,498,022 on 15th February, 2021. The overall number of Pakistanis infected with corona virus by that day was recorded to be 564,824. This means that Pakistan has been doing around 16.5 tests for each of its citizens found to be infected by the virus.

This number falls almost in the middle of a minimum global range – of 10-20 tests for each confirmed case – set by WHO. For Dr Faheem Younus, a leading health expert based in the University of Maryland, USA, this shows that “Pakistan’s Covid testing remains poor”.

He compares the number of tests being conducted in Pakistan with those in other countries. According to him, both the United Kingdom and the United States have tested as many as 800,000 people per every million members of their population; India and Brazil have tested much less – at 130,000 per million people – but their numbers, too, are far above Pakistan’s which has tested only 30,000 people out of every million of its population. It “ranks 156th globally” in corona testing, Younus wrote in a recent tweet.

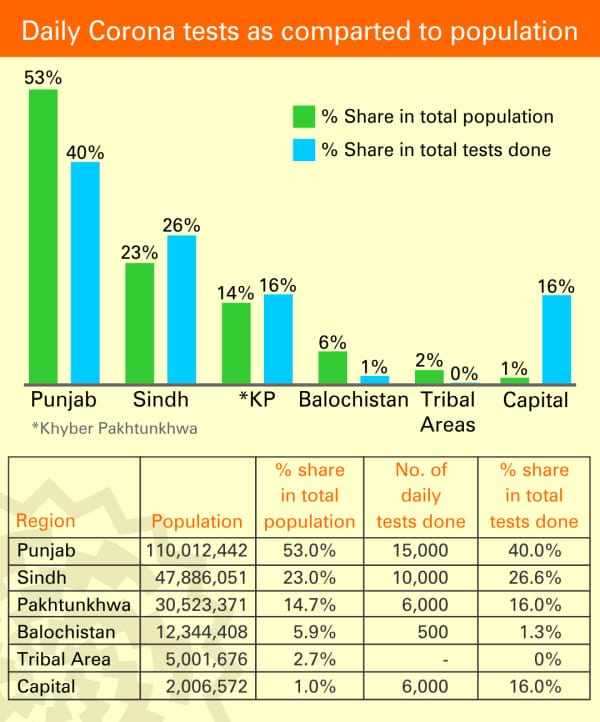

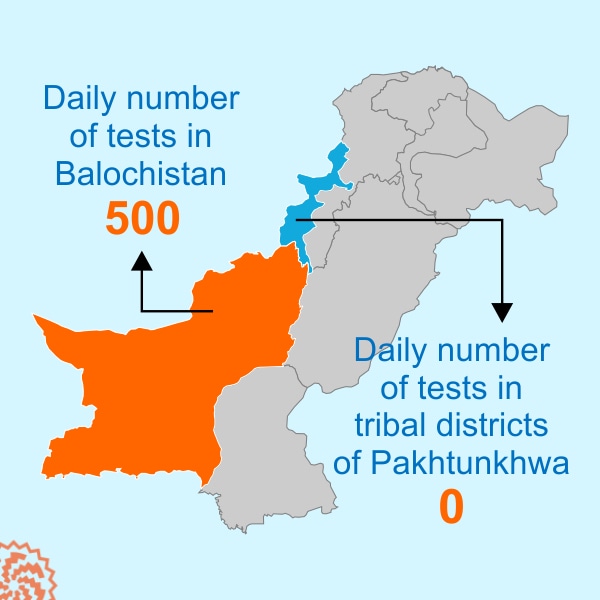

Even this number masks many internal imbalances. For instance, federal capital Islamabad has a much larger share in testing than its share in the national population. Similarly, the shares of Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (minus the tribal districts) in total testing are also higher – though by a small margin -- than their population share. On the other hand, not a single test has been done in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s tribal districts and only 500 tests a day are being done in the whole province of Balochistan which houses more than five per cent of Pakistan’s population.

A further breakdown of this data suggests that there are variations even within the provinces. For instances, most tests in Sindh are being done in Karachi and the bulk of tests being conducted in Punjab is taking place in Lahore.

Lahore also houses 32 of the 52 laboratories doing corona tests in Punjab. This is despite the fact that some southern Punjab districts – such as Multan and Dera Ghazi Khan – might have at times a higher number of corona-related infections and deaths than Lahore.

Testing facilities in Punjab:

This heavy concentration of testing facilities in Lahore is creating many problems for those living away from it. A woman residing in the largely rural district of Pakpattan complains that she had to travel to Lahore -- more than 185 kilometers from her home -- to get her corona test done.

Dr Shobha Luxmi, a Karachi-based expert on infectious diseases, is critical of this urban bias in the government’s corona testing mechanisms. She explains that “most laboratories in smaller cities and towns neither have the expertise nor the budget to conduct PCR tests”. This, according to her, is “because these tests require a lot of precaution in the collection and analysis of the sample which is possible only in metropolitan areas.”

Dr Luxmi, therefore, suggests the government rather introduce point-of-care testing at government hospitals located in smaller cities and rural areas. “Antigen tests could be conducted at these hospitals because these are easier to conduct, give quicker results and are better at detecting the infection,” she says.

The absence of such a testing mechanism that is equally available and effective throughout Pakistan, the government could have either severally under-counted the corona infections or altogether overlooked some of its more dangerous hotspots. A serological survey conducted by Getz Pharma, a pharmaceutical company based in Karachi, to assess the prevalence of corona virus in Pakistan seems to confirm at least the former apprehension.

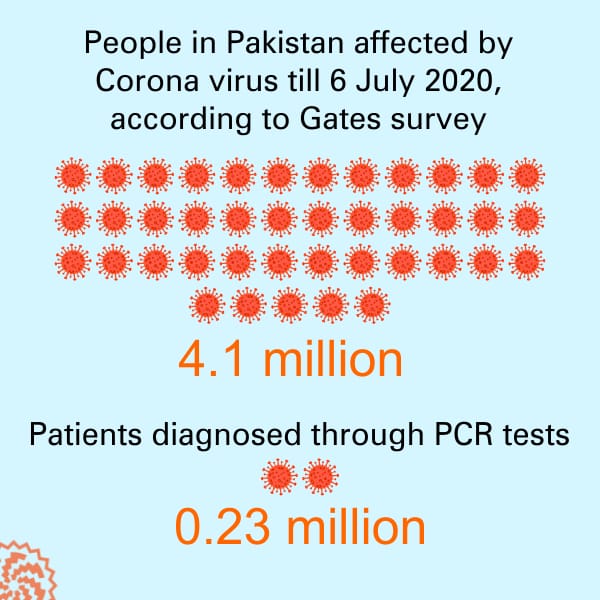

The Getz survey reveals that 4.11 million people in Pakistan had been infected with corona virus by 6th July 2020. This number is 17.7 times higher than 231,818 corona infections detected by then through PCR testing.

“With the current testing mechanisms, it is not surprising that many corona cases are going undetected, says Dr Luxmi. And then she warns, “We cannot aim to curtail the spread of the infections until or unless better testing mechanisms are employed by the government.”

Private testing

While the government testing is haphazard at best, the one being done by private laboratories in Punjab is far from being flawless. Haseeb Niazi, a resident of Lahore, has had an experience that just confirms that.

He says he gave his sample on 31st October 2020 to Chughtai Lab for corona testing because he had to travel to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) to visit his family. The laboratory gave him a result that showed him to be infected with corona virus.

Niazi says he had no symptoms and was barely exposed to the virus because he was taking precautions in his social interaction. So, he decided to get tested again the very next day – this time round from the pathological laboratory of the Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital. This second test found no corona virus in his body.

“I was very confused and did not know which report to believe. My entire travel plan and the exposure of my family members to the virus was dependent on my test results,” he says.

To get rid of the confusion, Niazi underwent another test after six days – again from Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital. Only when this test also did not find the virus in him did he travel to UAE.

He believes the government needs to regulate private laboratories to ensure that their testing facilities follow all the internationally acknowledged protocols and procedures to conduct the tests. “It seems the government is not paying any attention to the crisis of testing in Pakistan,” he says. Consequently, he argues, “there is no guarantee that your test has been done correctly even if you have paid 6500 rupees for it.”

An employee at Chughtai Lab, on the other hand, says test results are dependent on so many factors that it is possible for any laboratory to produce occasional false results. The accuracy of even the best test kits is not more than 70 percent, he says, so it is unlikely that every result that these kits produce is accurate.

Niazi, however, is not alone in complaining about the standard of private testing in Pakistan. Foreign airlines, too, have expressed similar concerns. For instances, Emirate Airline used to accept Chughtai Lab tests for its intending passengers during the first wave of the pandemic but it stopped doing that during the second wave.

Jahan Noor, 27, a British-Pakistani living in Lahore, blames this on how various laboratories do the testing variously.

She and her husband had to get tested before travelling to London recently so they decided to have the tests not at one but two laboratories in order to be sure about their health. “Each of them followed a different set of SOPs [Standard Operating Procedures]. At one lab, they only took a swab from one nostril while at the other they took the samples from both the nostrils as well as the throat,” she says.

All these complaints find no takers within the government though. The Punjab Primary and Secondary Health Department, responsible for overseeing the testing process in the province, is so opaque that it refuses to even talk to the media.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 22 Feb 2021, on its old website.

Published on 6 Jun 2022