Nawaz Iqbal’s cotton crop used to be so good that farmers would visit it from far and wide. He produced about 47 maund (1880 kilograms) of cotton from a single acre of land in 2015. This was 17 maund (680 kilograms) more than average per acre yield that year in his own district, Vehari.

Since then his cotton production has been steadily declining. Last year, he produced only six maund (240 kilograms) of cotton from one acre.

Iqbal, a resident of 178 EB village located 20 kilometres northeast of Vehari city, has been using genetically modified BT cotton seeds since 2005. He says these seeds gave a very good yield for the first ten years but later their production began to decrease every year. This, he believes, is mainly because BT seeds have lost their ability to kill insects that attack the cotton crop.

Kamran Malik, who returned to Pakistan to do agriculture after doing his MBA from England in 2014, also blames BT seeds for his declining cotton production. He plants cotton on 50 acres of land every year in Sui Wala village in Lodhran district and cites a research by an institution based in the United States to support his claim. Cotton-harming insects such as American Larva and Spotted Larva have developed immunity to fight against the genetic material placed inside BT seeds to kill them, he quotes the research as saying.

To solve this problem, he says, the authors of the research have suggested that at least 20 per cent of each BT cotton field should be planted with traditional cotton.

A United States government agency that regulates the cultivation of BT seeds in the United States has also advised American farmers to plant conventional seeds along with BT seeds to get a better yield.

Explaining this recommendation, Dr Shafqat Saeed, dean of the agricultural and environmental sciences department at Mian Nawaz Sharif Agricultural University, Multan, says: ‘’If powerful insects that attack BT cotton conjugate with relatively weak insects that attack the traditional crop then their next generation will not be as strong as the current generation of harmful insects. This way, BT seeds will easily kill the next generation of insects’’. If this process is repeated continuously for ten years, he argues, then the situation may be different from what it is now.

Malik also wants to follow this suggestion but no traditional seed is available in the market.

Dr Zafar Iqbal, director of the Agricultural Biotechnology Research Institute in Faisalabad, however, says one of the 17 cotton seeds approved by the government this year, GS Ali 7, is a traditional seed. He expects it to become available in the market in a few days.

Explaining the main reason behind the dearth of traditional seeds, Iqbal says 90-95 per cent of cotton in Pakistan is being produced from BT seeds. Seed traders, therefore, store and sell only these seeds, he adds.

A Pakistani history of BT seeds

BT is a bacterium that scientists at Monsanto, an American seed company, have incorporated into cotton seeds after transforming it into genetically modified organisms by using GMO technology. This bacterium kills Spotted Larva and American Larva in cotton crop as soon as these are born.

The work on this technology began in 1981 but Monsanto first tested it in 1993. Two years later, the United States officially approved the sowing of BT seeds so its cultivation began there the same year. In 1997, China also approved the sowing of BT seeds. These seeds reached India in 2002.

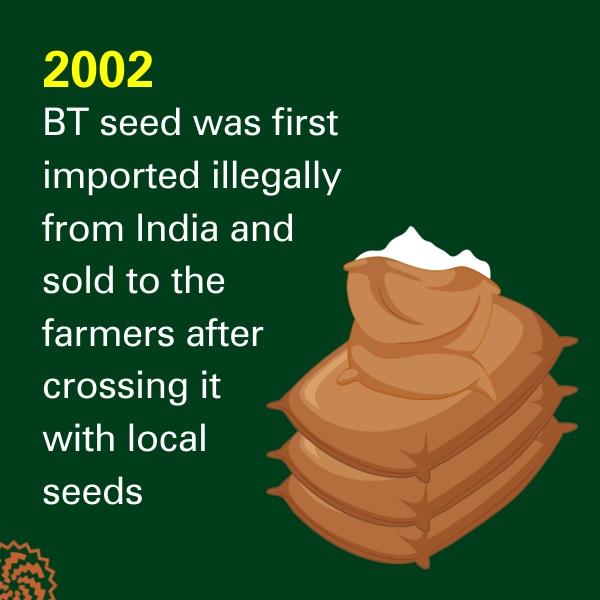

Professor Iqbal Bandesha, chairman of the plant breeding department at Islamia University, Bahawalpur, says BT seeds first arrived in Pakistan in 2002, although the method of bringing them here was illegal. According to him, a Pakistani company imported these seeds from India and started selling them by mixing them with local seeds – without seeking any permission from the government.

Monsanto initially made a big fuss over the sale but, Bandesha says, the company could not stop it as it had not registered its seeds in Pakistan. If Monsanto had registered its BT cotton seed in Pakistan then, under the seed act, no individual, company or institution could have used it for 12 years without paying a certain royalty to the company, he says.

A research paper presented at a conference in the United States in 2010 confirms all this.

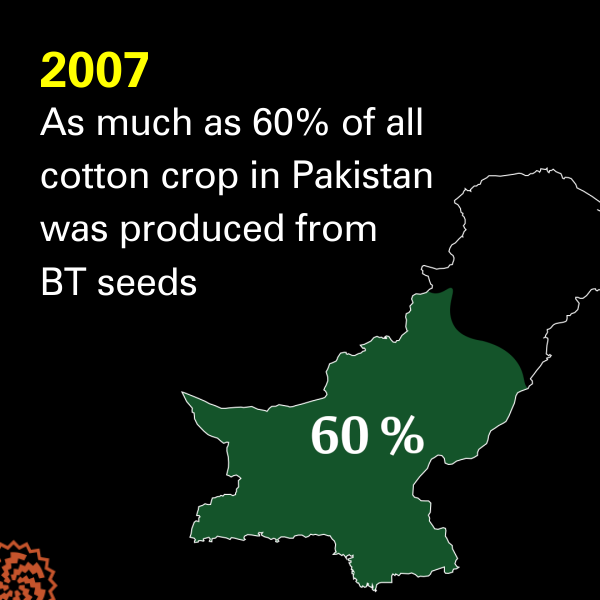

According to this paper, BT cotton seeds were brought into Pakistan in 2002 without the government’s permission but their cultivation was going on in many parts of the country by 2005. Two years later, these seeds were being used for 60 per cent of the cotton grown in Pakistan.

The paper says a survey was conducted in January and February 2009 to elicit the views of farmers in Bahawalpur district of Punjab and Mirpur Khas district of Sindh about the performance of BT seeds. The reason for the selection of the two districts for the survey was that BT cotton was being widely grown there.

The farmers told the surveyors that BT seeds cost more to grow because they were more expensive than conventional seeds and also required more water and fertilizers than other seeds did. They, however, said the yield of these seeds was much higher than that of the conventional seeds which was making cotton cultivation highly profitable.

The farmers in both the districts, however, did not know why and how BT seeds were different from other seeds and what was the actual purpose of their manufacturing. They did not even know if cultivating them created any agricultural or climatic hazards.

Despite this lack of knowledge, 40 varieties of BT seeds were being cultivated across the country by 2009, according to the Pakistan Agriculture Research Council (PARC). The proliferation of these varieties was caused by the fact that many Pakistani companies were extracting bacterial genes from the original BT seeds and transferring them to local seeds – thereby creating ever new varieties.

Also in 2009, the government initiated the process of legalizing the cultivation of BT seeds in Pakistan. According to a report published in the English language newspaper, Daily Times, in November 2009, a committee of the federal ministry of environmental protection recommended that two varieties of BT cotton named CEMB 1 and CEMB 2 be approved for two-year trial cultivation. These varieties were developed by Punjab University’s Center of Excellence in Molecular Biology.

At the same time, though, reports started coming in from India that BT cotton was failing there. These reports said the incidents of suicide among farmers were increasing due to the failure of BT cotton crops and these crops were also having a negative impact on local sheep.

Consequently, Pakistani farmers, too, started developing concerns about BT seeds. Some farmer organizations also started protesting against their approval and cultivation.

An organization called Kissan Board Pakistan finally filed a petition in the Lahore High Court in 2014 to stop the cultivation of BT seeds. It argued that these seeds had failed to control the pests that attack cotton and that there was no local research available on their harmful effects.

After hearing the petition, the Lahore High Court stopped the government in May 2014 from approving new varieties of BT seeds for cultivation unless a proper legal framework was made available to gauge the impacts of GMO technology used in them. The court also ordered the government to stop the sale and purchase of 37 BT seeds already approved for cultivation.

The government has never been able to implement that decision.

GMO technology: advantages and disadvantages

Dr Shaukat Ali, an assistant professor of agriculture at the University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, says two types of research is available regarding the GMO technology: One that is done by scientists working with government institutions in different countries and the other that is done with the financial support of Monsanto. The first type of research, according to him, shows that seeds produced under GMO can have negative effects on human life because they have been created by leapfrogging the natural system. The other type of research, however, repudiates these fears.

Researchers and analysts also worry that a few large companies could take over the world's agriculture, especially food production, with the help of GMO technologies. An article published a few days ago by a German news website, Deutsche Welle, points to the same concern. It says that only four major companies produce more than 50 per cent of the seeds used worldwide. These include German company Bayer (which has now bought Monsanto), American company Corteva, Chinese company Kim China and French company Limagrain.

Ali says the seed companies using GMO technology, especially Bayer and Cortiva, do not allow farmers to save seeds from a crop so that they can use them for sowing the next crop. “These companies force farmers to use new seeds for every new crop. This is being enforced through legislation done for the protection of plant breeders’ rights and plant variety protection,” he says.

The companies also use such technology in their seeds that stops them from growing if they are being reused. When farmers plant these seeds for a second time, they do not produce any crop.

Ali, therefore, wants the government and Pakistani farmers to save themselves from these exploitative tactics and, instead, turn to traditional seeds. He points out how Pakistan produced 12.2 million bales of cotton -- a record production -- in 1992, using traditional seeds. If our scientists can develop immunity in traditional seeds to withstand harsh weather and the government ensures the sale of high-quality pesticides then cotton production can be improved without using BT seeds, he argues.

Also Read

Corporate profit vs farmers' plight: Why DAP fertilizer price has risen sharply over the last one year

Dr Kausar Abdullah Malik, a known agricultural scientist and a teacher at Forman Christian College, Lahore, does not support these views. “If we can import soybeans made from GMO seeds for food then why can't we import BT cotton seeds to develop our textile industry?” he says.

He also argues that allowing a foreign company to bring good technology seeds to Pakistan does not mean that our research institutes should stop trying to produce good seeds on their own. If and when they are able to make better seeds, farmers will certainly start buying their seeds, he says.

Dr Shafqat Saeed also supports his point of view. He says Monsanto has now developed seeds that can easily control pink larva and other insects that suck the sap of cotton crop. Importing these seeds will improve cotton production in Pakistan because sap-sucking insects are the ones that cause the most damage to local crop, he argues.

According to him, the government has, indeed, tried multiple time to sign an agreement with Monsanto so that it can bring its BT cotton seeds into Pakistan through lawful means. The main reason that this agreement has not been signed yet is the inflexible stance of the company, he says. “Monsanto wants to have the exclusive right to sell BT cotton seeds when it brings their next generation to Pakistan. It also wants the agreement to be valid for a limited period of time and demands a hefty amount for that period,” he says. “The government, on the other hand, wants to buy the seed manufacturing technology from the company and then manufacture and sell the seeds on its own.”

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 4 May 2021, on its old website.

Published on 23 May 2022