When the police raided Muhammad Zeeshan’s house at 11:00 pm on 9th November 2020, they were looking for a particular mobile phone. According to them, Zeeshan had snatched that phone from its owner, Mohammad Ramzan, during an armed robbery.

Zeeshan, 31, is a resident of Lahore’s Baghbanpura area and works as a security guard at the Pakistan Post. Talking about the raid, his father Tauqeer Ahmed says: “We showed all the phones in the house to the raiding party.”

After inspecting them, the police told Ahmed about the model of the phone they were looking for. This reminded him that, some time ago, he had purchased a phone of the same model for his wife. Having developed some technical fault, it was not being used.

As soon as he showed that phone to the police, Ramzan, who was accompanying the policemen, confirmed that it was the same phone that had been snatched from him. Ahmad could not believe this. When he bought the phone, it was inside a sealed pack.

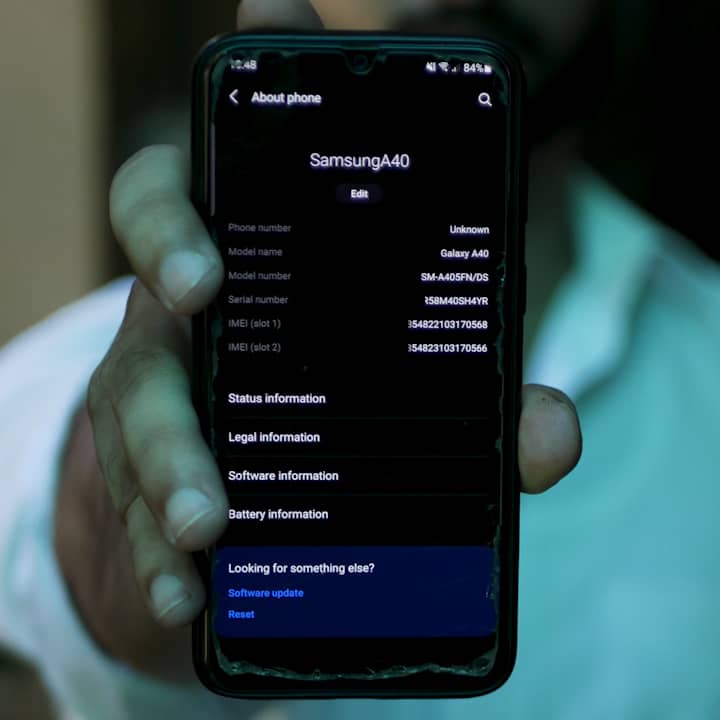

To his further surprise, when the police matched the phone’s IMEI (international identification) number with the identification number written in the first information report (FIR) about the robbery, they turned out to be the same.

He was alleged to have robbed Ramzan’s motorcycle showroom at gunpoint on 27th June 2020 in Mananwala town of Sheikhupura district and took away four mobile phones, a Rolex watch worth 450,000 rupees and 150,000 rupees in cash. The police took him to Mananwala where, he claims, he was forced to confess to his alleged crime though he kept insisting that he had nothing to do with the robbery.

Zeeshan, however, told the police during detention that he once had the controversial phone repaired so, he surmised, its IMEI number might have been changed during repairing. To refute or confirm this, the police spoke to the Lahore-based mechanic who had repaired the phone but could not reach any conclusion.

Zeeshan’s family, in the meanwhile, contacted the police and Ramzan and offered them that they were ready to provide any personal guarantee for Zeeshan’s release. They were worried that he might lose his job if he remained absent from it due to his detention.

Ramzan did not budge. He, instead, insisted that the only way for Zeeshan to secure his release was to pay him one million rupees in lieu of the robbed items.

Ramzan’s refusal to let off Zeeshan led the latter’s family to get details of the calls made and received from the phone at the centre of the case. This record proved that the phone was being used in their household even before the robbery. “All of us were shocked. How could it be snatched in Mananwala while it was also being used in Lahore?” says Zeeshan’s cousin, Muhammad Faisal.

When they presented these details to the investigation officer, they were allowed to meet Zeeshan for the first time after his detention. Ramzan, however, still refused to accept the call record as genuine.

So, the police extracted the details of calls made from the snatched phone. This record turned out to be different from that of the phone owned by Zeeshan’s family and, thus, proved that the two devices were not the same.

The police then asked Zeeshan’s family to have the call record of their phone verified from a special data cell at the office of District Police Officer, Sheikhupura. He was released once this verification proved that the call record was genuine.

But, during his 11-day long detention, Pakistan Post had issued him a show cause notice to explain the reason for his absence from work. He was also given a written warning to avoid being absent in the future or else he will lose his job.

“Who is responsible for all this suffering we have gone through?” says Faisal. “Was it the phone company’s fault because it mixed up the identification numbers of the two phones? Or was it the police’s ineptitude because they kept Zeeshan in custody for several days on the basis of an incomplete investigation and without registering any case?”

Here is an even more important question: how did two phones end up with the same identification number?

Something that happened to Manzoor Khan, a resident of Aamir Road area of Lahore, shows that mobile phone companies are mainly responsible for packing a phone in a box carrying another phone's identification number. He bought a phone from the electronics market at Lahore’s Hall Road on December 1, 2020. A few days later, at his friend’s suggestion, he compared the identification number on the phone with the one written on its box and found the two to be different. He then complained to the shopkeeper who had sold him the phone but, instead of informing the company, the shopkeeper just pasted the correct identification number on the box on his own.

How and why are IMEI numbers changed?

A mechanic, who repairs mobile phones in Lahore Cantt, says that one of the main reasons for discrepancies in identification numbers of phones is that Pakistani phone companies open every sealed box that contains an imported phone in order to put their warranty card in it. During this process, he says, it is highly likely that boxes get mixed up.

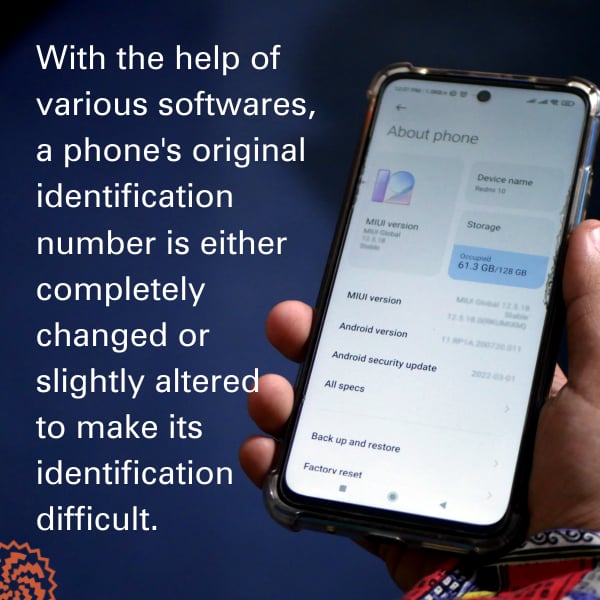

He also says thousands of phones operating in Pakistan were either brought into the country illegally or were taken away from their real owners during robberies and thefts. These phones are sold and bought secretly and, in most cases, their original identification numbers are either completely changed or slightly altered to make their identification difficult. Software used in the process are available with many people who buy, sell and repair phones, he says. “Different softwares are used for phones of different companies and models.”

An important incident in this regard came to light in September 2020 when Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) raided a mobile phone shop in Sheikhupura. During the raid, a man named Usman was taken into custody for allegedly altering phone identification numbers.

To deal with such problems, PTA has also introduced Mobile Phone Identification, Registration and Blocking System (DIRBS) from 1st December 2018. Using this system, anyone who has lost his phone for any reason can have it turned off temporarily or permanently by quoting the identification number written on it.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 15 Mar 2021, on its old website.

Published on 31 May 2022