Mohsin Jutt wanted to sell his wheat crop but the price the government was offering was less than what he wanted. Private buyers were also reluctant to pay more than that. So, on 18th April 2021, he posted a note on Facebook that he needed a buyer for his 3,200 kilograms of wheat. He was soon approached by several buyers and, after some bargaining, he was able to sell his wheat at 1,900 rupees per 40 kilogram. Thus, even while sitting at home, he earned one hundred rupees more than the government price on every 40 kilograms of wheat he sold.

A resident of 161 M, a village in Hasilpur tehsil of Bahawalpur district, Jutt says some farmers in his area had sold their wheat at 2,000 rupees per 40 kilograms so he, too, was looking for a buyer who could give him that kind of a price. But, his best efforts notwithstanding, he was unable to find a client who could offer that price. That is why he resorted to social media.

He says he could have received a higher price if he had waited for a few more days but he did not have any storage facilities and bad weather was making it impossible for him to keep his wheat crop in the open for long. Small farmers like Jutt cannot store their wheat for some other reasons as well. They have to sell their crop to fund their household expenses and to procure seeds and fertilizers for the next crop, he says. The government and private buyers take full advantage of this compulsion, he adds.

Jutt explains his point by citing the example of 2017 when, after a bumper wheat crop, the government left wheat farmers entirely at the mercy of private sector. Consequently, he says, the farmers had to sell their wheat to private buyers at far less than the official price of 1,300 rupees per 40 kilograms.

This year, however, the farmers have more than one buyer. Some of these buyers are also reaching out to wheat growers through social media -- just like a resident of Muzaffargarh district did. On 17th April 2021, he posted on Facebook that he needed 20,000 kilograms of wheat. He got the required amount very next day.

He says he has not purchased the wheat for personal use. Some urban households, indeed, had given him money a month in advance to procure it for them. Due to a sharp increase in flour prices last year, he says, many urban households are trying to buy wheat this year. They fear that wheat and flour prices will rise rapidly in the coming months, he adds.

Many medium-scale and large-scale farmers are also holding their crop instead of selling it now. They are also anticipating increase in wheat prices.

One of them is Amir Ghani, general secretary of a farmers’ association in district Rahim Yar Khan. He says the farmers had to sell wheat at the official price of 1,400 rupees per 40 kilogram last year but later private traders and hoarders sold it at 2,500 rupees per 40 kilogram. This year, he says, his organization has raised the slogan of ‘our crop, our price' and is telling the farmers to not sell their wheat until they get the best available price for it.

The farmers had to sell wheat at the official price of 1,400 rupees per 40 kilogram last year but later private traders and hoarders sold it at 2,500 rupees per 40 kilogram.

Who are private buyers?

Imran Farid, a farmer from Mithan Kot town in Rajanpur district of southwestern Punjab, received offers from several buyers even before harvesting his wheat this year. “Initially, the price offered by these buyers was same as the government price but it went up with time,” he says. Eventually, he sold 112,000 kilogram of wheat to a trader at a price higher than the government price by 50 rupees for every 40 kilogram.

Farid suspects that the buyer was either a representative of some seed company or a large-scale hoarder. Ghani also knows many buyers active in Rahim Yar Khan who are buying wheat from farmers in the name of seed companies and flour mills at more than the official price.

An official working in the provincial food department in district Dera Ghazi Khan says that not only Khyber Pakhtunkhwa-based flour mills are buying wheat -- after obtaining government permits -- from the farmers in the area under his supervision but many traders are also buying and smuggling it to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Though some seed companies, too, are buying wheat with the government permission, he says, a large number of hoarders are, in fact, using their name to buy and smuggle wheat.

Abdul Majeed Khan, Rahim Yar Khan’s district food controller, also admits that many hoarders are buying wheat this year under various pretexts. He claims he has registered cases against some people who were trying to smuggle wheat to Sindh.

Omar Draz, deputy director of the provincial food department, concedes that many people are buying wheat from different parts of Punjab claiming to be the representatives of seed companies and flour mills. But, he says, it is not always possible to confirm or refute their claims.

The Punjab government, however, is not taking any practical measures to curb such procurement of wheat.

Flour mill owners and seed companies, on the other hand, complain that they are not being allowed to buy wheat freely. According to Chaudhry Asif Ali, chairman of the Seed Association of Pakistan, about 300 seed companies need to buy between 500,000 and 600,000 tons of wheat this year from Punjab but the provincial food department and district administrations have hindered them from doing so. By the third week of April, by his reckoning, these companies could not procure even 100,000 tons of wheat.

The association, therefore, wrote a letter to Prime Minister Imran Khan a few weeks ago. It said that, due to the barriers to wheat procurement, “there is a fear that certified wheat seeds will not be produced in the country next year”.

Asim Raza, chairman of the Flour Mills Association, has similar complaints. He says the Punjab government has allowed flour mills in the province to purchase two million tons of wheat this year but ‘’achieving this goal is a long way away”. So far, he says, “we are having problems in meeting even our daily wheat needs”.

The Punjab government, according to him, has issued permits to flour mills to purchase wheat which are valid for only 72 hours. If mill owners cannot bring the wheat they have purchased inside the premises of their mills within that time, the procured wheat is “unloaded from their vehicles and transferred to the government warehouses”. He also claims that wheat was unloaded from some flour mills vehicles in Bahawalpur on 28th April even when the permit for its purchase was still valid.

Provincial food departments and Pasco will jointly procure about 6.5 million tons wheat, while the rest will be procured by private sector.

Provincial food departments and Pasco will jointly procure about 6.5 million tons wheat, while the rest will be procured by private sector.The government as a buyer

Wheat was cultivated on 16.67 million acres in Punjab this year and is expected to yield 19.6 million tons of grain this year. Keeping in view the needs of urban population, the Punjab government has set a target of purchasing 3.5 million tons of wheat this time – having set up 384 procurement centers cross the province for the purpose.

Last year, the Punjab government had set a target of procuring 4.5 million tons of wheat but it could buy only 4.3 million tons. Earlier this year, the Punjab food department had set the same target as it did last year but later this was revised downwards.

Draz says there was a shortage of wheat and flour in rural areas last year but the government could not do anything about it because its purchased wheat is supplied only in urban areas. The farmers, on the other hand, blame the Punjab government for that shortage because, in order to meet its own procurement target, they allege, it had forcibly taken away wheat they had kept for their domestic needs. Consequently, the amount of wheat available in villages was far less than what they needed.

This year, says Draz, the government has set a target one million tons less than what it was last year to avoid wheat shortage in rural areas. Also unlike last year, he says, flour mills are buying wheat directly from the farmers so the government has to buy less wheat even for urban areas than before.

In spite of these two factors, the provincial government is finding it hard to achieve its procurement target. Evidence for this was seen in many parts of south Punjab where, for instance, in Bahawalpur division about 95 per cent wheat had been harvested till 28th April 28 but the government could procure only 59 percent of its targeted wheat by then. Similarly, the food department had achieved only 52 percent of its procurement target in Dera Ghazi Khan division by 28th April. And, the procurement of wheat was 46 percent less than the target in Multan division till then.

Explaining the situation, Draz says that 70 percent to 80 percent farmers in Punjab are small landholders and do not have tractor-trolleys to transport wheat to the government procurement centers. ‘’They, therefore, prefer to sell wheat to traders who pick up their crops from the fields,” he says.

Aamir Ghani, however, believes the difficulties being faced by the Punjab government in procuring wheat are not due to the famers lacking means of transportation but due to the presence of buyers in the market who are giving the farmers a good price for their produce. “When private buyers are paying farmers more than the government price then why would they give their wheat to the government?” he argues.

Apart from the Punjab food department, the federal government’s Pakistan Agricultural Storage and Services Corporation (Pasco) also wants to buy 1.5 million tons of wheat from the farmers of Punjab. For this purpose, it has set up 239 purchase centers in 16 tehsils of Punjab. (A portion of this wheat is supplied to various federally administered areas, especially Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan, while the rest is stored so that it can be used to meet the country's food needs in case of an emergency.)

Pascoe, too, is also not getting the amount of wheat it requires.

Punjab government has allowed flour mills in the province to purchase two million tons of wheat this year but ‘achieving this goal is a long way away.

Punjab government has allowed flour mills in the province to purchase two million tons of wheat this year but ‘achieving this goal is a long way away.Umair Masood, general secretary of the Pakistan Kisan Ittehad and a farmer from Mian Channu tehsil in Khanewal district where Pasco is buying wheat, says it is difficult for Pasco to achieve its target because most farmers are not ready to sell their crops at the price set by government. This is despite the fact that the government is trying its best to bar private traders from purchasing wheat from the regions where Pasco is active.

A note posted on Pasco’s social media page on 24th April says middlemen in grain markets have been barred from buying wheat in areas where Pasco’s purchase centers are located. A food department official in Sahiwal region also confirms that wheat purchase licenses issued to middlemen in the area under his supervision have been revoked for the same reason.

Similarly, Asim Raza of the Flour Mills Association claims that flour mills, despite having the procurement permits, are facing great difficulties in procuring wheat from the tehsils where Pasco’s centers have been set up.

Risks and apprehensions

Wheat produced in Pakistan is divided into three equal parts. The farmers keep one portion for their own needs. The second part goes to the people living in rural areas and small towns who buy wheat instead of growing it themselves. The third part is used for providing flour to the urban population and to deliver wheat to areas where it is not cultivated. All public and private buyers are involved in buying and selling this last portion every year.

According to the federal ministry of food security, Pakistan is expected to produce 26.2 million tons of wheat this year (one million tons more than what it did last year). So, going by this estimate, this third portion amounts to 8.6 million tons. Of this, provincial food departments and Pasco will jointly procure about 6.5 million tons while the rest will be procured by private sector. The largest share in this will come from flour mills which have been given a target of buying two million tons this year.

Wasi Ahmed, an agronomist, does not see these targets being met. This is because a large portion of the current crop has already been purchased by hoarders, he says. They will either sell it to flour mills at higher prices or they will try to sell it in Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan after the government brings down its current restrictions on wheat procurement -- mainly because the government price of wheat in these provinces is 200 rupees (per 40 kilograms) higher than the price being given to the farmers in Punjab.

Also Read

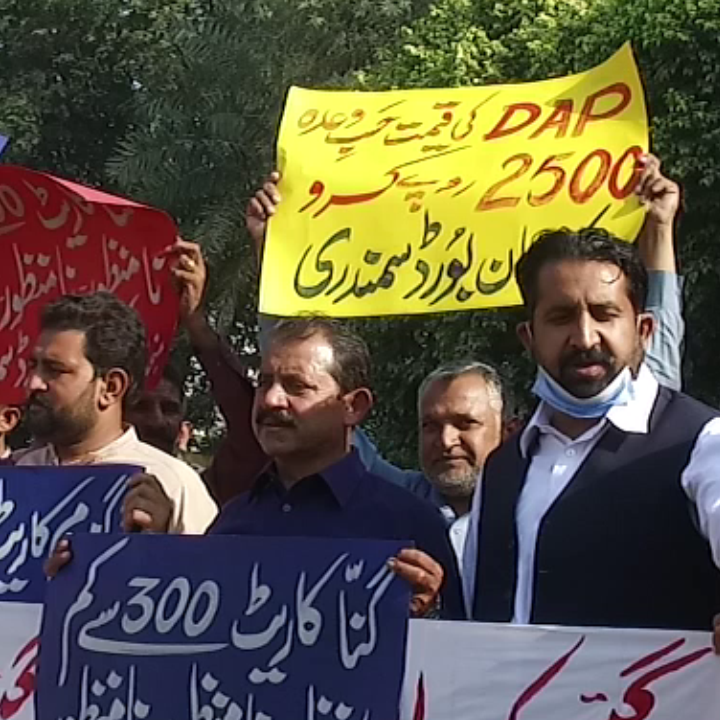

Corporate profit vs farmers' plight: Why DAP fertilizer price has risen sharply over the last one year

In either case, he says, the supply of wheat and flour in Punjab will decrease and their prices will go up. He argues that this increase will depend on how much of wheat the government agencies and flour mills are able to buy. If they fall far short of their targets, ‘’the price of wheat will reach 2,500 rupees per 40 kilogram in the next two to three months”.

Ahmed similarly explains that Pakistani wheat is less likely to be smuggled to Afghanistan, Iran or any other country for the time being because wheat’s current international price is close to its official price in Punjab. "If, however, the price of wheat in the world market goes up by 300 to 400 rupees per 40 kilogram then hoarders will smuggle it to Afghanistan and Iran too,” he says. Consequently, “there will be a shortage of wheat in Pakistan which will have to import it at higher rates”.

The federal government has already expressed its concern about the possible shortage of wheat in the country – though its estimates are not premised on smuggling but on general shortage of supply. According to the secretary of the federal food security department, Pakistan will need 29 million tons of wheat this year -- including 1.2 million tons for seeds for the next crop and 1 million tons for storage in the government reserves. On the other hand, Pakistan’s maximum wheat production this year is expected to be 27 million tons which is at least two million tons less than the country’s total demand.

Due to this difference, Federal Minister for Finance Shaukat Tareen is reported by an English newspaper on 27th April to have said that this year Pakistan will have to import three million tons of wheat. The price for this imported wheat will definitely be higher than the country’s domestic wheat price.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 23 May 2021, on its old website.

Published on 22 Mar 2022