Phalia Sugar Mill has been shut down for the last seven years.

Located in central Punjab’s Mandi Bahauddin district, the mill was initially owned by the Gujrat-based family of Chaudhry Zahoor Elahi, a renowned politician of the 1970s. Chaudhry Shujaat Hussain, a scion of the same family, laid its foundation in the late 1980s when he was federal minister for industries.

The mill has been at the centre of some serious financial controversies after running smoothly for quite some time.

A National Accountability Bureau (NAB) report claims that Pervaiz Elahi, a prominent member of Chaudhry family, asked the then president of the Bank of Punjab, Hamesh Khan, in 2007 to find a buyer for the mill. By virtue of being the chief minister of Punjab at that time, Pervaiz Elahi was also the constitutional head of the bank.

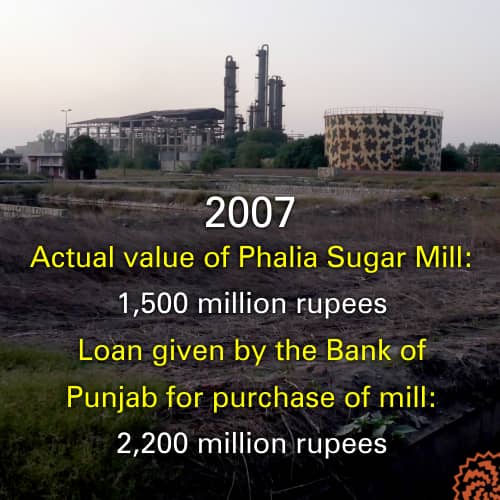

Hamesh Khan, the report goes on to state, first contacted the then federal minister for industries, Jahangir Khan Tareen, but he showed no interest in the deal. Later, Hamesh Khan succeeded to convince a known business house, Colony Group, to buy the mill. The Bank of Punjab subsequently gave the group a loan of 2.2 billion rupees for buying it.

Interestingly enough, a director of Colony Group, Fareed Mughis Sheikh, was also a member of the board of directors of the Bank of Punjab at that time. In other words, he was simultaneously present among those who approved the loan and those who were its recipients. No one, however, pointed to this clear conflict of interest then.

Colony Group subsequently bought the mill in 2007 with 2.2 billion rupees it had borrowed from the Bank of Punjab. NAB, on the contrary, estimates that the real value of the mill at that time was 1.5 billion rupees.

The mill’s name also appears, at least twice, in the Pandora Papers, published last month. In the first instance, these papers refer to it indirectly, stating that both Chaudhry family and Colony Group are among 700 Pakistani individuals and business enterprises which own offshore companies.

In the second instance, the papers mention it directly. They reveal that Pervez Elahi’s son, Moonis Elahi, who is also the incumbent federal minister for water resources, held a meeting with an offshore wealth management company Asiaciti Trust in January 2016. He wanted the company to help him form a trust abroad to purchase 24 per cent shares of Rahim Yar Khan Sugar Mill and two properties in England.

When asked about the source of money for these, Moonis Elahi showed the sale deed of Phalia Sugar Mill to Asiaciti Trust to prove that his family had 2.2 billion rupees in its kitty.

Before sealing the deal, however, Asiaciti Trust engaged a media company, Thomson Reuters, to prepare a report about the source of money. Released on January 21st, 2016, this report was largely based on news stories broadcast and published by Pakistani news media. It raised questions over the transparency of mill's sale and stated that the Bank of Punjab itself had informed NAB about the suspect manner employed to secure the deal.

That unfavourable report notwithstanding, Asiaciti Trust agreed to take Moonis Elahi as its client and subsequently helped him register a trust in Singapore and the Pacific island of Samoa. But it told him that, under an international convention to combat tax evasion, he will have to submit all the relevant documents with the Pakistani tax authorities. He, however, ended his communication with the company at this point.

Laying waste to lives?

Covering an area of 138 acres, two kanals and 16 marlas, Phalia Sugar Mill has the capacity to produce 7,500 tons of sugar, 135,000 tons of ethanol (also called alcohol) and 48 tons of liquid carbon dioxide every day.

Though the mill continued producing sugar between 1990 and 2014, its ethanol manufacturing unit has faced difficulties since the very start. This was largely due to its hazardous emissions that adversely affect the health of people and animals in its surrounding area.

To minimise the effects of these emissions, Chaudhry family operated the alcohol unit on a limited scale (because they could not afford the ire of the people which could cost them electorally). But with no political stakes, Colony Group started operating it without any break and also without taking any safety measures.

According to Hafiz Moazzam Mahmood Gondal, a resident of Phalia Tehsil and the Gujranwala division president of Kisan Board Pakistan, a farmers’ body, this had a predictable effect. With the mill becoming fully functional in 2007, he says, environmental pollution in the villages around it registered a massive increase due to its hazardous emissions.

In addition, the extremely toxic effluent of the mill polluted the groundwater of all the nearby settlements. This contaminated water not only became unsuitable for human consumption but it also had a negative impact on the crops irrigated with it. “If an animal happened to pass through the water channel made to take the mill's waste to a nearby drain, its body would be burnt,” he says.

The ashes emitted from the mill also started causing serious illnesses among local people.

To find an amicable solution to these problems, residents of the area requested to the mill owners to mix some clean water with its effluents to decrease their level of contamination. But, as Gondal puts it, the obstinate mill management gave them short shrift.

After exhausting all the means to resolve the issue bilaterally, the disappointed residents of 26 affected villages, finally, decided to move the government. They filed applications with all the concerned departments complaining about the pollution the mill was causing.

Taking action on one such application received on March 10th, 2010, the district administration of Mandi Bahauddin eventually ordered the immediate closure of the alcohol unit until practical steps were taken to curb the spread of pollutants.

Refusing to comply, the mill owners filed a petition before a local civil court, asking it to overturn the district administration’s order. The court, however, upheld the order. The judgment is issued on April 6th, 2010, stated the alcohol unit would remain closed until the management of the mill installed the machinery that can reduce the level of contaminants emitted by it.

Over the next five years, the case reached the Supreme Court of Pakistan via the Lahore High Court. Both these appellant forums, however, upheld the decision of the civil court.

It’s the money, stupid!

After purchasing Phalia Sugar Mill, Colony Group included it in a company called Colony Sugar Mills which also owned another sugar mill located in Mian Channu town of Khanewal district.

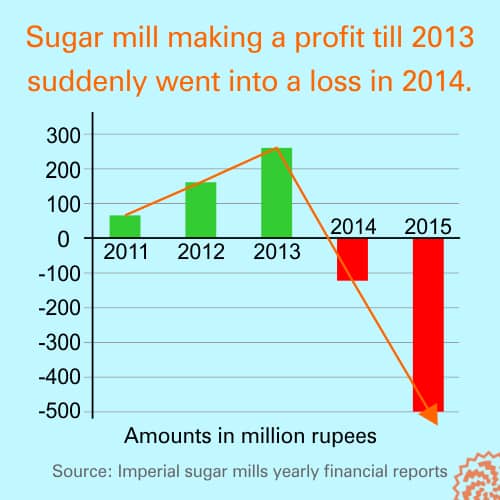

The first annual financial report of Colony Sugar Mills shows that both its sugar mills and its alcohol-producing unit earned a net profit of 300.9 million rupees in the year ending in September 2009. (Its net profit in the previous year that had ended on September 2008 was 42 million rupees.)

The report for the following year reveals that Colony Sugar Mills produced more sugar in 2010 than it did in 2009 but its profit decreased to 118 million rupees. Consequently, its share price in the stock exchange fell from 3.12 rupees to 1.19 rupees. The management of the company attributed this situation to increase in sugarcane prices.

The data given in its next financial report shows that Colony Sugar Mills' profit further decreased to 65 million rupees in 2011 – as also did its share price that came down to 0.66 rupees. In 2012 and 2013, however, the company's profits soared again. In the first of these years, it made a profit of 160 million rupees; in the second, its profit jumped to 262 million rupees.

The company then experienced a sudden reversal in its fortunes in 2014, incurring an after-tax loss of 126 million rupees. In the following year (2015), the Supreme Court verdict eventually forced it to shut down the alcohol unit. Finding it impossible to keep the unit running, its management shut down the sugar-producing unit of Phalia Sugar Mill as well.

The company's financial report explains the rationale for this decision. While it shows that its sugar-making units incurred losses in 2014, the alcohol unit was still earning a profit. The company could not afford to run its loss-making parts when it had to close down its part that was running in profit.

It was perhaps because of this reason that Naveed Mughis Sheikh, another director of Colony Sugar Mills, categorically told the district administration in a meeting that he would not run the sugar unit if the alcohol unit was not allowed to operate, says Gondal. At the same time, though, he was not ready to take steps needed to reduce the environmental impact of the mill.

A meeting of the directors of Colony Sugar Mills, in the meanwhile, was held on January 30th, 2016 in Lahore in which they changed the name of the company to Imperial Limited. A report presented at the meeting stated that the company bore a total loss of 499.7 million rupees in 2015.

Another report submitted to the directors in 2016 stated that the sugar mill in Mian Channu had been sold for five billion rupees (and that money had been used for repaying loans to various banks). The same year, the directors asked the company's shareholders to let them sell Phalia Sugar Mill as well.

Also Read

Growers await payment six months after selling their sugarcane crop to Pasrur Sugar Mill

The sale somehow has not materialised so far. A meeting held in January 2021 was told that the mill has not been sold due to Covid-19 pandemic and other financial issues. The participants of the meeting were also informed that the present value of its land, building and plant stood at 8.765 billion rupees and that the company wanted to set up a natural gas-run power generation plant after selling it.

A living hell

Sajjad Hussain's pale complexion, dark circles around his eyes and his trembling hands and lips suggest that he might have just got out of a hospital. Stricken with anxiety, sometimes he scratches his face and then starts massaging his legs.

A resident of Karmanwala village in Phalia tehsil of Mandi Bahauddin district, he was living a happy and healthy life a few years back. He was then working as a storekeeper at Colony Sugar Mills' Phalia unit for a monthly salary of 14,000 rupees. His two children, aged four and six at that time, were receiving free education at a school run by the mill.

Its closure in 2015 made his life miserable.

Losing a job made it hard for him to educate his children and run his household. When he could not find a job after a year and a half of wandering around, he somehow managed to move to Dubai.

His job there went well till 2018 but then his health started deteriorating due to his irregular working routine which made him perform his duty sometimes during the day and, at other times, during the night.

His visa also expired during this period but he could not extend it on time due to his illness and his financial troubles. This forced him to work secretly and, that too, only on odd jobs.

Eventually, Hussain informed his uncle (who is also his father-in-law) of the situation. He arranged 400,000 rupees for him to pay as the fine imposed on him for over-staying his visa in Dubai. This allowed him to come back home in July 2019.

After his return to Pakistan, his health continued to deteriorate and the multiple diseases he was suffering from rendered him too weak to do any work. He says his weight before going to Dubai was about 62 kilograms. It is only 37 kilograms now.

“Had the mill not been closed, today my [health and financial] condition would have been altogether different,” he says.

Hussain, 40, explains the general economic condition of his village by reciting a couplet by a renowned poet, Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi: “You might fancy villages as a paradise but I have seen derelict houses in them.”

Hundreds of families living in Karmanwala and several other villages around it are facing the same plight as he does. The mill, he says, employed about 1,500 people, mostly coming from its nearby villages. Most of the young men of these areas are now working in other cities or they have shifted to Dubai and Saudi Arabia for work. This explains why mostly children and old people are seen in Karmanwala that consists of about 300 households.

The closure of the mill has also resulted in multiple problems for 50-year-old Muhammad Arshad, a resident of the same village. He joined it in 1990 and continued working here till its closure in 2015. The last monthly salary he received was 20,000 rupees while his two sons and two daughters received free education at the mill-run school.

Since he neither owns any agricultural land nor has any other financial resources, he started working as a construction worker after losing his job. After some time, though, he developed various illnesses – just like Hussain -- and became bed-ridden. Consequently, he had to discontinue the education of his two sons prematurely. They were only 12 and 14 then. He then put them to work. They now look after the cattle of a local landlord to make ends meet.

Muhammad Faisal also contributed to this report.

Published on 27 Nov 2021