On August 1, as Saddia Mazhar embarked on an inDrive ride from Centaurus Mall to Savours Food, a restaurant in Blue Area, she did not anticipate the traumatic experience that awaited her. While en route, Saddia received a call from a friend inviting her to join a hiking trip on Trail 5. She ended the call by suggesting that her friend meet her at the restaurant before proceeding. It was like any regular phone call people make while travelling in ride-hailing vehicles.

However, things took an unexpected turn when the driver casually mentioned to Saddia that he had intended to go for a hike that morning but couldn’t, inquiring if he could join her. She turned down his proposal politely, yet the situation didn’t end at that point.

The driver insisted once more, urging Saddia to call her friend and ask her not to come, suggesting that Saddia join him instead. She introduced herself as a journalist, hoping this would make him stop. But the driver also mentioned he’s from the media community and that it doesn’t matter. Soon after, they arrived at their destination, and the driver left Saddia at the back entrance of a well-known fast food chain. As she got out, he again insisted that she buy food from there and sit with him in the car until her friend arrived. This offer left her speechless and scared. She quickly paid the fare, exited the car, and hurried towards the busy area.

This wasn’t Saddia’s first time in Islamabad, as she had lived here for 12 years before moving back to her hometown of Sialkot. She uses the inDrive app whenever she travels to Lahore or Islamabad for work.

The driver waited outside, hoping she might change her mind. He repeatedly called and even messaged her on WhatsApp. Saddia promptly contacted another friend and requested him to pick her up. “At that point, I was terrified. I couldn’t understand what was happening. I kept looking over my shoulder because I feared he would come after me.” Saddia tells Lok Sujag. She blocked his number and breathed a sigh of relief when her friend arrived.

As she narrated the traumatic experience to her friends, they urged her to post her story on Facebook for awareness and to lodge a complaint with inDrive customer service. Saddia used the in-app complaint feature but had not received any response until this piece was written. “I don’t think they will even check my complaint. InDrive’s customer service is unreliable; they don’t follow up on complaints, and I find it useless,” says Saddia.

She says she has developed strong nerves as a journalist over the years. However, she partially blamed herself for not responding more firmly to the driver. “I should have firmly told him off instead of remaining quiet and polite. Polite behaviour isn’t always an option for women in our society. It took me a day to regain my composure and behave normally without constantly worrying. I can’t imagine how difficult it must be for other women, especially young girls, who go through such incidents and harassment problems with these drivers,” Saddia says.

Saddia’s experiences are not isolated. In March 2023, numerous similar stories surfaced on Twitter, leaving women feeling vulnerable and raising serious concerns about the safety protocols implemented by ride-hailing platforms.

Sidra Kiran, the communication representative of inDrive for the Pakistan-South Asia region, informs Lok Sujag that immediate action was taken against the driver about whom several women had complained in March. “His account has been permanently suspended, preventing him from accessing our platform.”

On May 19, another inDrive user, Fatima, had a similar encounter. While settling into the backseat of a cab at around 9:15 pm, she caught the driver sharing her contact details with someone on the phone. Soon after, the driver received another call and casually revealed Fatima’s drop-off location to the person on the other end.

With a mounting sense of danger, the 24-year-old could no longer ignore the situation and questioned the driver about sharing her details on the phone. As the driver slowed down the car, she swiftly gathered her belongings and hastily opened the door, making a quick escape.

Her first instinct was to blend in with the crowd and find a safe place to call the 15 helpline, who assured her they would send help immediately. She sought refuge in a shop in a nearby market’s basement. However, despite the 15-minute wait, no police assistance arrived. She finally reached home safely by 10:30 pm after a friend dropped her off.

Just six months before this incident, in November 2022, Fatima had been left pondering whether she had narrowly avoided a “kidnapping or rape attempt” when she had leapt off a moving inDrive bike. This incident occurred on a lonely road close to Margalla Hills in Islamabad after the driver allegedly missed two exits.

Another woman, Zara*, opting to remain anonymous, relies on inDrive as a safer choice for her daily commute from the National University of Sciences & Technology (NUST) to Islamabad’s Blue Area. However, her feeling of security was shattered when she experienced harassment during a typical ride. In September 2022, she was riding with a familiar driver who had given her and her colleagues rides before. During this ride, he requested her assistance with the navigation on his phone. To her astonishment, she noticed a pornographic website displayed on his phone. Zara refused to take the phone and once she reached her workplace, she told her coworkers about the incident and cautioned them against riding with that driver. This distressing event significantly impacted Zara, causing emotional turmoil and continuing fear.

The unreliability of public transport in Pakistan and Uber’s discontinuation of its services in five major cities in October 2022 prompted numerous passengers to seek an alternative, leading them to inDrive. This choice was driven primarily by inDrive’s distinctive bargaining feature and cost-effective rates. A San Francisco-based company, inDrive became Pakistan’s most downloaded ride-hailing app within just one year of its launch in 2021, amassing 5.6 million downloads.

The analysis conducted by Data Darbar, a website that tracks investment flows within Pakistan’s tech ecosystem, has also unveiled that inDrive has risen as the dominant player in the country’s ride-hailing market. Surpassing its competitor, Careem Pakistan, inDrive’s app has been downloaded almost twice as often.

Since their introduction in Pakistan, ride-hailing services have faced criticism for their failure to prioritise safety for women, who constitute a significant portion of their target market, and individuals from marginalised communities.

A 2019 Digital Rights Foundation (DRF) study titled “Ride Sharing Apps and Privacy in Pakistan” revealed that 28 per cent of customers felt physically unsafe while utilising Careem or Uber.

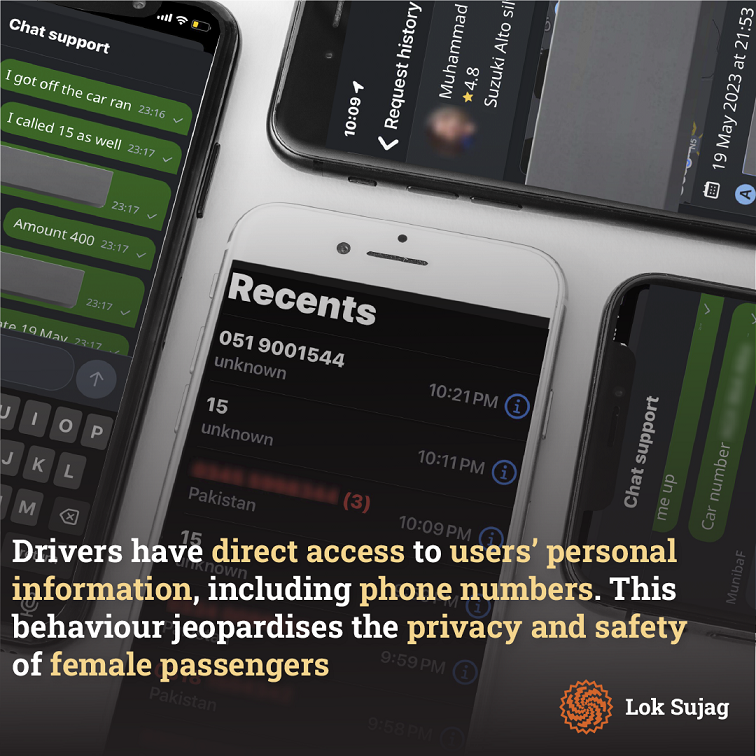

Direct access to personal details

Another concerning issue raised by women who use ride-hailing apps is that drivers have direct access to users’ personal information, including phone numbers. This behaviour jeopardises the privacy and safety of female passengers. It is not uncommon for drivers to call female customers after they have completed their rides, leading them to feel uneasy and uncomfortable.

Farida, a 30-year-old IT professional, frequently receives unsolicited calls from inDrive drivers. Originally from Chitral, she has lived in Islamabad for the past 12 years and has used various ride-hailing apps. However, the growing trend of men reaching out to her after completing their rides is causing her concern.

In May 2023, Farida and her friend were en route to F-7 Markaz in an inDrive car when the driver began asking for unnecessary personal information. The following morning, she started receiving messages from unknown numbers on WhatsApp.

“At first, I didn’t know who was messaging me. When I saw the WhatsApp display picture, I realised it was the same driver from the night before,” says Farida.

After realising this, she stopped responding to his messages. However, he persisted in asking for her address. “He asked me to share my address with him because he ‘wanted to send some gifts’. I ended up blocking him,” she tells Lok Sujag.

Safety measures

Passengers are advised by ride-hailing services to verify the driver’s information on the app, including their name, vehicle number, and model, to ensure it matches the details of the arriving vehicle at their location.

Nevertheless, repeatedly cancelling rides might not always be practical for customers facing such situations, given the limited availability of rides at any given time. Moreover, individuals might also risk reaching their intended destination late.

To ensure a safer travel experience, many women adopt additional safety measures when using ride-hailing apps.

Within the inDrive app, a ‘Safety’ button is provided for customers to share their routes with friends and family. An ‘SOS’ button also enables passengers and drivers to contact an ambulance or the police during emergencies.

However, according to Zara*, despite this option, inDrive’s “complicated” user interface makes it challenging to navigate the app. So, as a precaution, she captures screenshots each time she books a ride and shares them with her family or friends. Additionally, she carries pepper spray and a sharp key for added safety.

For Fatima, who left home six years ago and maintains limited contact with her family in Peshawar, sharing her live location isn’t a viable option. She also believes this practice breaches her privacy and independence. “I navigate this by following Google Maps, keeping an eye on the road and carrying a dagger for personal safety. I also opt for drivers with a minimum 4.8 rating,” she says.

Amid the escalating harassment incidents, women have also raised concerns about the absence of support and customer care from inDrive.

“When such incidents occur, you don’t have the luxury of time to retrieve your phone and type out a message on the chat,” says Fatima. The company doesn’t permit attaching pictures/screenshots without their authorisation and imposes a specific limit. The only option for further communication remains the text option. In contrast, with Careem, a user has the convenience to call customer services directly,” she points out.

InDrive is operational in major cities across Pakistan, including Karachi, Lahore, Multan, Faisalabad, and Islamabad.

Kiran mentions that inDrive has introduced multiple mechanisms and checks to guarantee passengers’ safety and contentment. She informs Lok Sujag that the company diligently verifies and assesses all documents related to driver and vehicle competence, such as CNIC, driver’s licence, and vehicle papers, before taking them on board.

She says that there is an in-app panic button to ensure safety, allowing passengers to share their location with friends and family. Additionally, every ride is geo-tagged, offering an extra layer of security.

To ensure a secure inDrive experience, Kiran outlines a general safety procedure, stating, “If a passenger faces imminent danger, their priority should be their own safety. They should take necessary precautions, such as leaving the vehicle if it’s safe, seeking a public area, or contacting our support team or local authorities. We encourage passengers to share their experiences and want to assure them that their complaints will be treated seriously.”

However, Fatima feels her complaint was not taken seriously. In the case of the November incident, inDrive informed her that action had been taken against the driver. However, when it came to the incident in May, her complaint was closed by inDrive without any action being initiated.

Zara’s experience was no different. She says that even after lodging a complaint with inDrive regarding a driver who had been messaging her, she “wasn’t contacted by inDrive’s customer service”. This has left her uncertain about their subsequent actions. “Instead, the driver contacted me again, questioning why I had filed a complaint against him.”

On the other hand, Farida says that complaining is useless due to the recurring nature of these incidents. “I’ve refrained from involving the police or cybercrime agency because I doubt any action would be taken. Such incidents are becoming commonplace, and as an individual woman, how many complaints can I lodge?”

Kiran says that the company offers round-the-clock support services to users, accessible through the support chat within the app or via email. The procedure entails selecting “support” from the app menu, responding to questions regarding the city and the nature of the issue, and subsequently clicking “start chat” to commence the dialogue with a live chat support agent. Following these steps, customers can connect with the support team and receive assistance with ride-related queries.

Also Read

Gender equality in inheritance: What men can have but women can't

Kiran says that when customers file complaints against drivers, they should include relevant evidence or documentation to support their claims. This evidence may comprise the incident’s date, time, location, and specific driver behaviour details. The subsequent action taken against these complaints depends on the gravity of the case and could range from issuing warnings to the driver to suspending or terminating their employment.

The complaint investigation process involves an internal inquiry, during which the driver is allowed to present their perspective, and any available eyewitness accounts are considered. In more severe instances, inDrive might aid passengers in pursuing legal action against the driver by providing essential information and collaborating with law enforcement authorities.

Laws & Remedies

Many women, including Saddia, Zara, Farida, and Fatima, are reluctant to report harassment incidents to the police or the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) due to awareness gaps, mistrust in the justice system, and the perceived lack of seriousness from the police. Waiza Rafique, a human rights activist and lawyer practising in Pakistan, emphasises that numerous women opt not to report such incidents despite legal provisions. One of Rafique’s clients, who faced harassment and blackmail from an Uber driver, endured a year-long struggle for justice.

“She gave up on multiple occasions due to being frustrated with how long it took,” says Rafique.

The police only agreed to register an FIR after Rafique’s client approached the Magistrate. A complaint was also filed with the FIA Cyber Crime Wing in Lahore, which investigated the case and found the captain guilty. “In 2019, he was imprisoned for a year and paid a fine of Rs 50,000,” says Rafique.

Two options are available for registering complaints with the FIA Cyber Crime Wing: submitting a complaint through an online form on the agency’s website or providing a handwritten application at their office.

The Digital Rights Foundation (DRF), an organisation addressing digital rights issues in Pakistan, reports receiving a limited number of ride-hailing app-related complaints on their helpline. In 2022, DRF received eight complaints about Careem and inDrive, encompassing issues like abusive messages, unsolicited explicit content and stalking.

According to DRF, this is because women don’t know how and where to report harassment due to their lack of knowledge about cybercrime and other existing laws. Secondly, when they try to report it through the police or FIA, their complaints are not registered properly.

The Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) is the primary criminal code in Pakistan and contains provisions related to various offences, including harassment. Section 509 of the PPC deals with “word, gesture, or act intended to insult the modesty of a woman” and can apply to cases of harassment in public transport.

The Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (PECA) contains multiple sections dealing with online harassment and protection. Sections 18, 19, and 21 address cybercrimes against the dignity and privacy of a natural person. However, they do not directly deal with harassment against women in public or private transport.

In cyberstalking cases, the offender can be penalised under Section 21 of the PECA if they commit the offence using “cyberspace with the intent to coerce, intimidate, or harass any person.”

When a victim registers a complaint, they should ensure that the investigation officer assigns them a complaint number to follow up. DRF guides and assists victims with the necessary documentation and the procedure of registering complaints with the FIA. They also take up pro bono cases in Lahore to help the victims.

Rafique also emphasises the importance of raising awareness and training the police to handle harassment complaints with seriousness and sensitivity without dismissing complainants. She recommends increasing the representation of female officers and the trans community to achieve gender equality and balance within the police system. A gender-inclusive approach will also help the police emergency helpline 15 to address complaints of harassment more efficiently.

While ride-hailing apps such as inDrive provide an alternative to inadequate public transportation in Pakistan, women say they must be held responsible for failing to ensure women’s safety. These platforms must enhance safety protocols and background checks and promptly address drivers engaged in inappropriate behaviour. Similarly, collaboration among individuals and organisations is essential to promote digital and legal rights awareness, empowering women to assert their rights when confronted with harassment or assault. By tackling these issues, we can work towards a safer and more inclusive transportation environment for women in Pakistan.

Published on 30 Aug 2023