About Us

The news media in Pakistan possesses the promise to end marginalization and democratize civic and political space but its business model hinders it from materializing that promise. Since it is heavily dependent upon advertising, it remains focused on where the sponsors and audiences of that advertising are – that is, Islamabad, Lahore and Karachi. The interests of the two biggest advertisers – the government and the corporate sector – thus become inextricably intertwined with the business interests of the news media. The media, therefore, not only mirrors the political ostracism of a vast majority, it also reinforces the marginalization of religious minorities, ethnic and linguistic communities and socially and politically suppressed individuals, ideas and identities.

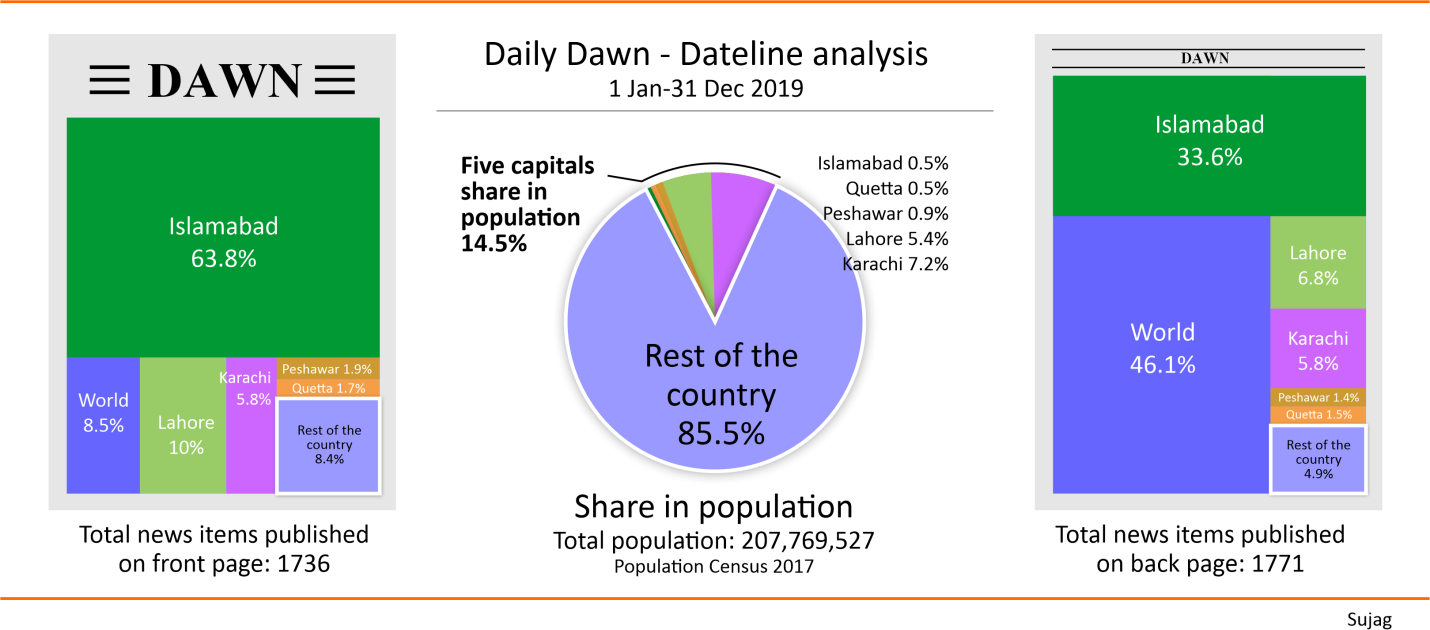

A short study done by Lok Sujag confirms the geographical bias of the mainstream news media. Consisting of a dateline analysis of the news items published on the front and back pages of daily Dawn between January 1 and December 31 in 2019, the study chose Dawn because it is not only among Pakistan’s best known newspapers, it is also believed to have one of the largest reporting networks in the country. It shows that two third of the newspaper’s front page and one third of its back page were occupied by the news originating from the main center of power – Islamabad. If we take into account other centers of power, that is, provincial capitals, only 8.4 per cent of the front page and 4.9 per cent of the back page is left for the ‘rest of the country’ where 85.5 per cent of its population resides.

Over the entire period covered by the analysis, not a single news report appeared on either the front or back page that was reported from five districts of southern Punjab – Layyah, Muzaffargarh, Rajanpur, Bahawalnagar and Lodhran. Three other districts of the same region – Dera Ghazi Khan, Rahimyar Khan and Bahawalpur – were together datelined only six times on these pages. These eight districts have a combined population of 25 million – which equals that of Australia – and includes a large number of the poor residents of Punjab.

The fact that power – and not people – is at center of the news media discourse continues to show in the provincial breakups of datelines. Of the 229 news items from Sindh province that made it to the front and back pages of Dawn, 89.1 per cent originated from Karachi. The province’s remaining 23 districts were only worth 25 news items. The capitals of Punjab and Balochistan also respectively occupied 77.7 per cent and 78.6 per cent of the provincial shares of news items. It was only relatively better for Pakhtunkhwa with Peshawar datelined news items taking 58.2 per cent of the provincial share.

The news media’s focus on covering the centers of power, indeed, goes beyond these numbers. Consider the case of wheat and wheat flour.

The news media’s focus on covering the centers of power, indeed, goes beyond these numbers. Consider the case of wheat and wheat flour.

Millions of farmers across Punjab, which is Pakistan’s veritable wheat basket, have been demanding for four years (2015-19) that the government increase the crop’s support price because their cost of sowing it has gone above their earnings from it. Their demand has seldom, if at all, found any mention in the news media, thus allowing two successive governments to ignore it. Yet, the news media cried itself hoarse when wheat flour shortages hit Lahore and Karachi in early 2020, forcing the government to promptly order wheat imports and crack down upon its hoarding and smuggling. Not just that, it also had to set up a commission to investigate the reasons for wheat flour shortage.

This editorial bias becomes even more pronounced in electronic media. One reason being that, while newspapers have to have a reporter in an area to cover local issues, electronic media also needs to provide its reporters with equipment and technical support for shooting video footage and transmitting it to their central offices. Private television channels have generally avoided making these expenses.

The case of coverage of Olympian javelin thrower Arshad Nadeem, Pakistan’s latest sports hero, provides an excellent example in this regard. He lives in a village near Mian Channu in district Khanewal where he trains without even basic facilities. Though he has won medals in a number of international competitions and is the first and only athlete in the country’s history to have qualified for Olympics on merit, he never made it to the news because he lives in an area that is ‘out of range’ for what is dubbed as the mainstream electronic media.

All of the television channels, therefore, preferred to ignore his potentially popular story until he was made popular by a social media video produced by Lok Sujag. But even after that, only Geo could ‘afford’ to make its team in Multan to take a 1 hour 30 minute trip to Mian Channu and film the sports sensation. When the Tokyo Olympics finally happened, in August 2021, Arshad was, of course, all over the media but even then television channels relied solely on official footage of the games. BBC Urdu was the only one to have bothered to go to Arshad’s village to produce a video on his family and his fellow villagers celebrating his Olympic performance.

This amply demonstrates that the electronic media is as constrained in its outreach as the print media. The nature of competition in electronic media sector is another factor that bars television channels from diverging from the immediate and direct interests of urban consumers. The channels work under a constant pressure that if they broadcast anything that does not interest their audience, even for as short a duration as few minutes, the audience will use its remote control and immediately switch to a different channel. This pressure forces more editorial compromises upon them than a similar pressure could possibly do for the print media.

The financial crunch posed by both political factors and the flight of advertising revenue to social media has further concentrated the news media into few large urban centers. Though their cost cutting measures have hurt their operations even in main stations -- Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad -- the outposts other than these cities have faced the biggest axe. Daily Jang has reduced its Multan edition staff to a small bureau and Dawn has closed down its Hyderabad bureau, relying on the services of a few freelancers. These developments will only further marginalize the non-metro areas in the news media discourse.

Technological advancements, at least in theory, can allow the digital news media to increase its editorial outreach and audiences across the country since the availability of internet and smart phones has made it increasingly easier to procure and disseminate news. But to finance its operations, the digital media has to invent a new business model that is not dependent on advertisements otherwise it will have to rely only on click-baits or follow the mainstream media outlets in exacerbating the processes of marginalization.