About Us

marginalization

/ˌmɑːdʒɪn(ə)lʌɪˈzeɪʃ(ə)n/

noun

treatment of a person, group, or concept as insignificant or peripheral

The phenomenon of marginalization is certainly not unique to Pakistan. Yet it is important for us to elaborate it within a Pakistani context -- with all its nuances and intricate details – because that is what lies at the core of our work. But, as is the case with most intellectual exercises, this elaboration has to be open-ended so that it can expand in the future to areas and subjects that remain unexplored so far.

With this condition in mind, we base our understanding of marginalization on the following factors:

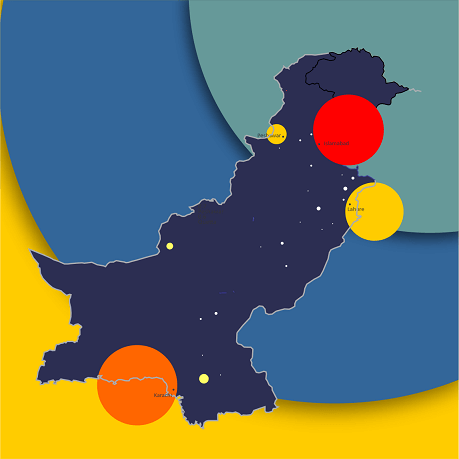

Pakistan is a big country with breathtaking geographical diversity. From the world’s highest mountain ranges in north to a vast desert and a reasonably long coastal line in its south and from fertile alluvial plains in the mid-east to mineral-rich arid and rocky swaths in its mid-west – the country is more diverse than most countries under the sun.

The obvious corollary of this is that Pakistan is inhabited by a large number of communities with unique histories, economies, social structures, cultures and politics. The state of Pakistan fails to acknowledge this diversity as a source of strength. It is in fact afraid of it. Since its inception in 1947, it has seen this diversity as an obstacle in its project of building a nation on the unitary principles of one religion, one language and one country.

Historically speaking, the first major expression of this mindset was the ruling elite’s refusal to accord a national language status to Bengali which was then spoken by a majority of Pakistanis. Bengali, of course, has a strong, centuries-old literary tradition and was routinely used in all the facets of statecraft in pre-independence Bengal. Yet the state of Pakistan saw it as a barrier in the way of its notions national unity and, therefore, wanted to impose Urdu in its place.

The first decade of the country’s history was, thus, wasted in bitter tussles between the ruling clique and the Bengali polity. As the formulation of the constitution was delayed and those at the helm of affairs continued to rule on ad hoc basis, they invented the concept of One-Unit that divided Pakistan into two ‘equal’ wings. Bengalis, however, considered this division as an attempt to marginalize them.

The same scheme resulted in the clubbing together of four distinct polities – Punjab, Sindh, Pakhtunkwa and Balochistan – as West Pakistan. All of them were required to renounce their centuries-old identities and instead switch to a new single identity overnight. The enforcement of this single identity required that any political and/or cultural assertions to the contrary were to be deemed treasonous. This, in turn, alienated and marginalized all but those who were opportunistically aligned with the state for personal gains. The One Unit experiment not only failed miserably in blending all the disparate parts of West Pakistan into a single whole, it also strained and distorted their mutual relationship.

When political arm-twisting and highhanded administrative tactics failed to achieve their intended result of fostering a single national narrative, the state brought out the gun. Thus began Pakistan’s long history of military rules which has time and again used violent strategies to smother the country’s diversity in the name of creating ‘one-nation’. Though the One-Unit scheme was abandoned in 1969, each subsequent martial law practically converted the whole of Pakistan into a single administrative unit, subjecting it to newer and more disastrous nation-building experiments.

This mindset continues unabated to date in various forms. At present, the diversity-is-a-problem outlook is expressed through opposition to the 18th Constitutional Amendment enacted in 2010 to devolve a number of governance sectors to the four provinces. Each province, consequently, can have a different policy on the same subject – and that is seen as a ‘problem’.

Just to appreciate that we are not talking about some tiny regions, consider this: Punjab has as many people as the whole country of Philippines; it has 30 per cent more inhabitants than Germany; population of Sindh is more than that of Spain and close to that of South Korea; and Pakhtunkhwa has more inhabitants than Canada.

The state’s obsession with unity and its refusal to accept, respect and celebrate its diversity has been a permanent source of marginalizing all those individuals, communities, polities and ideas that disagree with the state on how the country’s constituent parts should come together.

Diverse identities – premised on differences in geographical, social, economic or political factors – do not necessarily have to be mutually antagonistic, unable to coexist peacefully in one state. In fact, one of the major achievements of the modern state is its ability to institute systems that facilitate a smooth relationship between different – even competing – identities. Federalism and democracy provide the foundation for these systems. But that is where Pakistan has floundered in a big way and right from the beginning.

Military rulers took these different identities as a Lego set and played around with them – discarding some and using others to create objects of their own desire. Ayub Khan introduced a presidential system on the back of his hand-picked Basic Democrats. Ziaul Haq saw political parties as a menace and introduced party-less elections that resulted in toothless legislature. Pervez Musharraf was interested in ‘cleansing’ the political arena and midwifing a whole new political class through his local government system. In recent time, the state’s tactics have become subtler and more secretive than ever before but they continue to obstruct and complicate the country’s journey on a democratic path.

But, as we have seen, none of these ‘ingenious’ systems could survive and Pakistan had to limp back to a democratic transition. This start-stop trajectory towards democracy, however, has led to the development of state institutions which are neither responsive and accountable to the people nor are they representative and reflective of the country’s diversity.

The state’s democratic deficit has led to a stunted growth of political institutions as well. Today, no political party has grass-roots level structures in place. No primaries are held anywhere in the country to elect party office bearers or to choose electoral candidates. No party has constituted a leadership development program and a well aid-out career trajectory for its members.

Political parties, in fact, operate like business networks of political families that align with or against each other in various combinations and permutations before every election. These changes, in turn, trigger a superficial process of realignments at the lower rungs of politics.

The absence of a stable and effective local government system is partly both the cause and effect of this rootless politics. Every political and military government has tried to use this essential constituent of democratic deepening for its own vested interests. Since their respective interests have been at odds with each other, Pakistan has been experimenting with a new local government system every ten years. As things stand today, local government elections are already overdue in every part of the country but the provincial governments are again busy redesigning the system.

The absence of local-level structures within political parties and the lack of a durable and consistent local government system together have become a major hurdle in the process of political demand formulation at the grassroots level and its communication to the political and policy elite. This, in turn, has resulted in a structural disconnect between the power-focused elite discourse and the demands and aspirations of the people at large. This disconnect, too, works as a major driver for the processes of marginalization in Pakistan.

The quest for a Muslim religious identity was woven in the warp and woof of Pakistan as it came into being through a blood-soaked partitioning of the British-ruled India on religious grounds. A fervent debate, however, still rages about what role the founding fathers had in mind for religion in the new country’s public and political spheres.

Irrespective of the conflicting claims regarding their interpretation of religion’s place in the state and the society, the ruling elite did realize early that religion can serve as a useful tool to sustain the status quo and suppress dissent. It was, after all, the only common denominator for all the diverse geographical and political identities obtaining in the new country. The ruling elite, thus, found it convenient to package its disrespect for diversity in the deceptively simplistic rubric of one nation, one religion and one language.

The first manifestation of this packaging came about when the constituent assembly passed the Objectives Resolution in 1949 to put Islam at the core of Pakistan’s state narrative. Unsurprisingly, a major political and constitutional challenge that emerged immediately was the status of its non-Muslim citizens. This challenge was complicated by the Muslim clergy’s desire to turn the country into a theocracy. The ruling elite could not keep them completely out of power corridors because they were the original owners of what became ‘the Islamic card’. Though legal instruments that proactively discriminate against non-Muslim citizens were enacted much later, the process of their marginalization started at the very outset.

The strategy of thoroughly Islamizing both the state and the society, though, was continuously challenged by ethno-linguistic contestations. Particularly in East Pakistan, a surging Bengali nationalism offered a counter-narrative to the state-supported Muslim nationalism. But even after that part of Pakistan became Bangladesh, the state refused to revisit its fateful pursuit of its religion-centric narrative.

On the contrary, it renewed and strengthened that narrative by giving religious actors a prominent place in political and public spheres. By the time Gen Ziaul Haq took over Pakistan in 1977, ‘the Islamic card’ accrued geo-political capital too. His regime joined a West-funded scheme to defeat the ‘Godless’ Russian invaders of neighboring Afghanistan, investing heavily in religious educational institutions within its own territory. Their founders were provided with piles upon piles of cash and lethal arms and their students received military-grade training in guerrilla warfare. This military-religious complex, on the one hand, marginalized secular political voices entirely, on the other it transformed millennium old religious polemics into bloody sectarian street fights. The success or failure of sectarian ideologies, thus, became proportional to their capacity to inflict terror.

This deadly turn of events exponentially increased the capacity of ‘the Islamic card’ to create and deepen division in society along sectarian lines, marginalizing those who could not match others in men and weapons. These communities do not just comprise the followers of religions other than Islam but also several smaller and weaker sects within Islam.

Instead of putting an end to this maelstrom of sectarian enmities, the state selectively and secretively supports one or the other actor for short term gains on internal or external fronts. It believes that it has mastered the art of playing with fire without burning its fingers – even though evidence often proves otherwise. Political parties, too, try their hand at using ‘the Islamic card’, making moves to deflect the flames of religious hatred on to their opponents.

We identify this continued engineering of religious ideology as a major driver of the processes of marginalization in Pakistan.

Lok Sujag believes that a continuous process of marginalization is a major hindrance in realizing the dream of a democratic, pluralistic, peaceful and prosperous Pakistan. We are also of the firm belief that this process can be checked and reversed effectively only if we create and develop institutions that can bring the marginalized identities, ideas and individuals into the mainstream.

Such mainstreaming, however, has to find its way through a thicket of social and political discourses which are heavily dependent on the news media. This suggests the obvious: that the news media can offer the most efficient and effective means to mainstream the marginalized. With a fast-expanding access to information and communication technologies, the importance of digital news media in this regard cannot be over-emphasized.

The technological revolution, undoubtedly, is not an unmixed blessing since it is creating newer and deeper divisions than bridging the old ones. Yet, at Lok Sujag, we strongly believe that, supported and guided by our community, we can work successfully for an equitable and inclusive society that conducts its affairs in a participatory and democratic manner.