Is climate change rewriting the agricultural

narrative in Pakistan?

By Asif Riaz | Posted On : Dec 20,2023.

Once thriving as a highly successful and innovative pomegranate grower, Muhammad Hassan Bukhari's region held a unique standing and reputation for its contributions to pomegranate production. However, the disruptive force of climate change altered this landscape significantly. Today, he neither commands a significant presence in pomegranate cultivation nor maintains his city's reputation for this reason. The impact of climate change has not only transformed Bukhari's role as a grower but has also affected the city's standing in the realm of pomegranates.

Mohammad Hassan comes from the Tehsil Alipur in the Muzaffargarh district of South Punjab. Until a few decades ago, this region bore the title "Alipur Anar Wala," which resonated widely, earning Alipur considerable fame. Historical records, notably the

District Gazette published in 1929 during British rule in India, attest to the extensive cultivation of pomegranate gardens covering more than 4 thousand acres in Alipur tehsil then.

The renown of Alipuri White Pomegranate transcended borders, captivating palates not only in India but also finding appreciation in England, thanks to its exceptional taste and sweetness.

Hassan observes that the heightened intensity and prolonged duration of heat and rainfall in his region have increased, resulting in the demise of pomegranate orchards due to various diseases.

At 55 years old, Hassan reflects that until the 1990s, pomegranate plantations dotted the landscape of Alipur village, with local farmers reaping threefold profits compared to other crops. Government data further validates this, indicating that Punjab was the leading pomegranate-producing province in the country until the 1990s, with Alipur Tehsil contributing to 80 per cent of the province's yield.

During that period, Mohammad Hassan maintained a 25-acre garden, which, according to him, faced significant repercussions from the floods of 1998 and 2010, coupled with the accelerated rise in summer temperatures and the prolonged duration of monsoon rains.

According to his account, he decided to dismantle a 15-acre pomegranate orchard in 2007, with the remaining 10 acres succumbing to diseases by 2015.

Not just Hassan but the majority of cultivators in Alipur confronted similar challenges. As per the Punjab Agriculture Department, as recently as 2008, the cultivated area for pomegranates in Muzaffargarh district encompassed 1650 acres. However, due to a rapid decline, by 2022, only 331 acres of pomegranate orchards remained in the region.

Saad ur Rehman, an agronomist concurrently serving as an agricultural officer in the Department of Agriculture (Extension), has contributed significantly to understanding pomegranate issues, diseases, and the effects of climate change. His body of work includes published research papers addressing these critical topics. According to him, the climate in Alipur has evolved from being hot and dry to exceptionally hot and humid. This shift has intensified pest attacks on various crops, notably impacting pomegranates in the region.

According to him, the pomegranate, characterised by its bushy nature, features roots that extend no deeper than 10 to 12 feet, relying solely on them to absorb water and nutrients. This resilient plant can endure temperatures up to 40 degrees Celsius. However, the underground water levels in this area have significantly declined and with temperatures reaching up to 50 degrees Celsius, the adverse impact on the plant's pollination process has become evident.

Climatic shifts in Pakistan, impacting regions such as Alipur, Balochistan, and the entire country, have led to a significant 42 per cent decrease in the area under pomegranate cultivation over the past decade. The ramifications of this decline are substantial. Pakistan, previously spending approximately 33 crore rupees on imports until 2012 to fulfil domestic pomegranate demands, faced a substantial increase, with expenditures soaring to seven billion and 37 crore rupees in 2022.

Ek anar sau bimaar

Hassan observes that, besides pomegranates, the conditions for cotton and wheat crops in his region are unfavourable too. When he undertook wheat cultivation on 20 acres of land on October 20 this year, the germination process faced challenges, necessitating the use of seeds again. According to him, this issue arose due to temperatures exceeding 30 degrees Celsius during wheat cultivation.

He elucidates that there is either a rise in temperature or the onset of rains during wheat cultivation and when the grain production stage begins in March-April.

2022 Muhammad Hassan cultivated wheat on the same acreage as the previous year. However, when the crop ripened, a hailstorm devastated four acres, leaving the remaining 16 acres yielding only 31 maunds per acre.

On March 30, 2023, the Crop Reporting Service, a subsidiary of the Punjab Department of Agriculture, released a report indicating that, due to rain and hailstorms, a total of 8,27,829 acres across the entire province, including Muzaffargarh, suffered partial damage, while 30,500 acres were entirely affected. This follows a pattern from the previous year when the wheat crop faced challenges in Punjab and throughout the country.

The year 2022 proved unfavourable for wheat farmers as well. The crop faced challenges in March and April of that year due to extreme heat. According to the Meteorological Department, March and April 2022 marked the warmest period since 1961.

Saim Rasheed Chaudhry, an agricultural expert who served as an agricultural consultant for the UAE government from 2003 to 2018, emphasises, "Typically, after one hundred and ten days of wheat cultivation, the pollination process begins, ideally during the spring season." However, he notes, "Due to climate variability, this season is absent in most years, and the rapid transition from hot weather to winter causes wheat kernels to mature before attaining their normal weight and size." This significantly diminishes overall productivity.

The average yield in Pakistan over the last five years stands at 29.35 maunds per acre, which lags behind the five-year average yield of neighbouring India by six maunds. According to Saim, a potential solution to address this shortfall lies in altering the crop pattern of wheat, specifically by advancing it by 15 days. Given that the food supply for 24 crore people depends on wheat production, this adjustment could play a pivotal role in mitigating the deficiency.

According to the latest economic survey, wheat serves as the staple food for more than 24 crore Pakistanis and contributes significantly to the agricultural sector, adding 8.2 per cent in value and to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 1.9 per cent. As per the World Bank, Pakistan's requirement exceeds 30 million tons, while the current production hovers between 26 and 27 million tons, resulting in a three to four million tons shortfall. The country imports wheat from the volatile global market to bridge this supply-demand gap. This presents a grave concern in a nation where 40 per cent of the population faces severe food insecurity.

Dr Javed Akram, heading the Wheat Research Institute under the Punjab Government's jurisdiction, echoes Saim's concerns. He asserts that the impact of climatic changes has hindered the effectiveness of government institutions' hard work and research. According to him, despite the challenges, there are now seeds available in Pakistan capable of enhancing production per acre by an additional six maunds.

Dr Javed Iqbal highlights another disheartening development, expressing that, owing to severe weather conditions, farmers are forgoing wheat cultivation in districts where the average yield per acre is typically the highest.

Over the past decade in Punjab, there has been a 35 per cent decrease in the area under wheat cultivation in the Sahiwal Division, a 17 per cent reduction in the Multan Division, and an 8 per cent decline in the Faisalabad Division.

Conversely, in the Rawalpindi Division, the area under wheat cultivation has witnessed a substantial increase of 40 per cent during the same period.

Furthermore, in response to the challenging and unfamiliar weather conditions in traditionally wheat-fertile regions, farmers are increasingly inclined to shift from wheat cultivation to planting mustard. In 2022, mustard was cultivated on an expansive area of one and a half million acres in Punjab, marking the highest in Pakistan's history.

As per Dr Akram, this scenario is additionally problematic as, in regions witnessing a rising trend in wheat cultivation, the cultivated area is limited, and the average yield per acre is less than half.

The cotton conudrum

According to a report by the World Bank, Pakistan stands among the ten countries most profoundly impacted by global climate change and natural disasters. The country has witnessed an annual average temperature increase of approximately 0.63 degrees Celsius in the past century. This trend is particularly problematic for agriculture, as a one-degree Celsius rise in average temperature could lead to a 5 to 10 per cent reduction in crucial food and cash crop production.

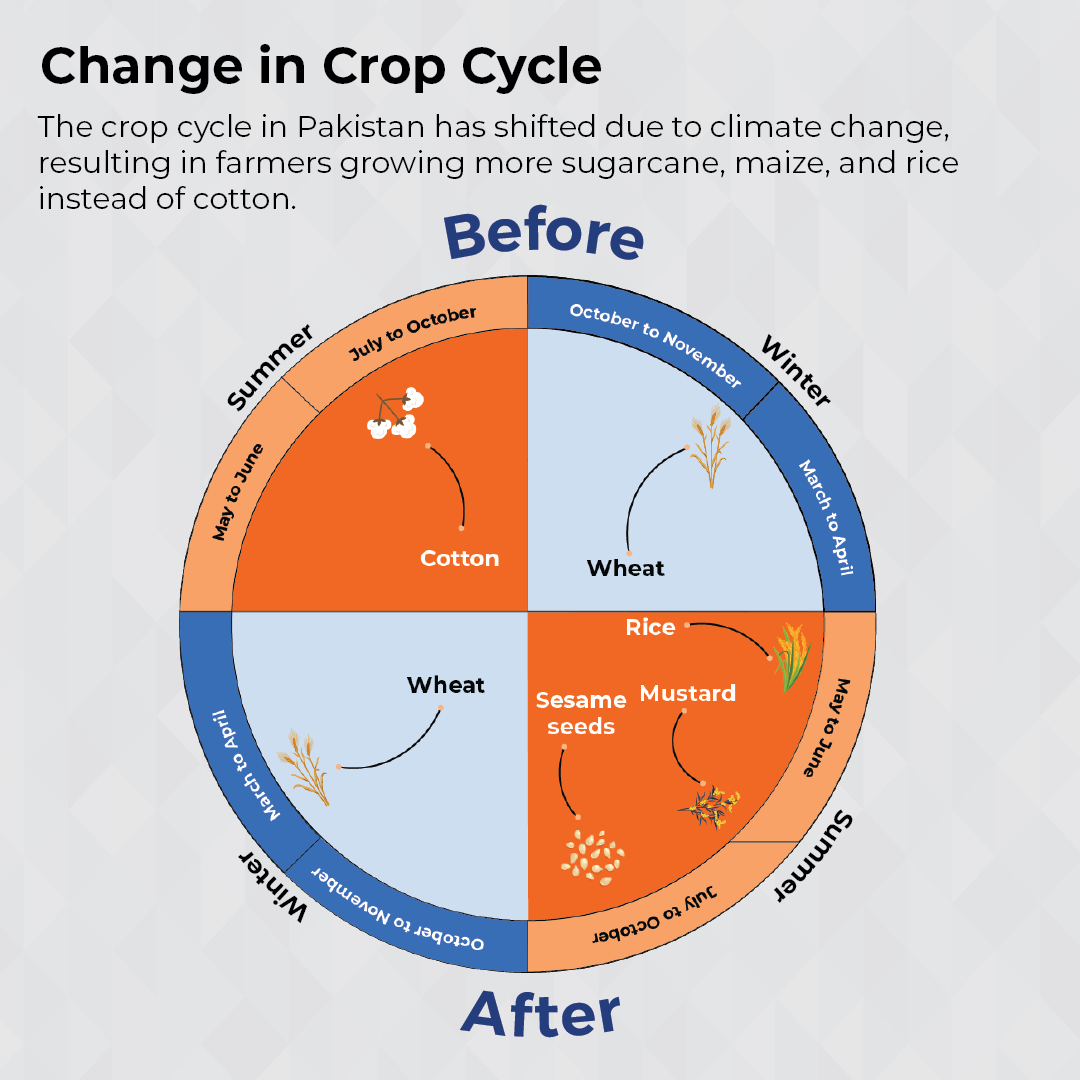

In Pakistan, cotton, a vital cash crop, has experienced significant impacts over the last 30 years. An examination of official data reveals that since 2005, the area dedicated to cotton cultivation has dwindled by 39 per cent, accompanied by a staggering 47 per cent decline in production. In Pakistan, a one-degree Celsius increase in temperature corresponds to an 8 per cent decrease in cotton yield per acre.

Over the past 30 years, cotton yield demonstrated improvement when the average temperature remained equal to or lower than the national average. For instance, in 2005, Pakistan achieved a record production of 1 crore 42 lakh 65 thousand 200 bales of cotton. Dr Jahanzeb, a scientist at the Ayub Agriculture Cotton Research Institute operating under the Punjab Agriculture Department, explains, based on data from his office, that the temperature and rainfall during the 2005 monsoon (Kharif) season were below average.

Following 2005, the 2014 season brought encouragement for cotton and cultivators, resulting in the production of 1 crore 39 lakh bales in Pakistan. Meteorological department reports highlight that, similar to conditions in 2005, during July, August, and September 2014, air humidity, rainfall, and temperature remained below the national average.

He posits that climate change has inflicted the most significant impact on the cotton crop, and it is disconcerting that the areas with the highest concentration of cotton cultivation have experienced the most pronounced effects.

Official data additionally indicates that South Punjab, contributing to approximately 85 per cent of the provincial production, has witnessed the most substantial fluctuation in cotton production over the past 30 years.

Over the last 30 years, there is merely a one per cent difference in the decline of both area and production in Okara and Sahiwal districts. However, the contrast has escalated to six per cent in Vehari, 10 per cent in Multan and Muzaffargarh, and 18 per cent in Bahawalpur. In Rahim Yar Khan District, cultivation and production per acre have experienced a 13 per cent reduction.

Ibad ur Rehman, the proprietor of 25 acres of agricultural land in Kot Kotla Dewan, Jampur Tehsil of Rajanpur District, faced substantial losses this season. Having planted cotton crops on 15 acres of land, he had to bear a financial setback of one million rupees.

He notes that everything was progressing smoothly until mid-July, but an unexpected attack of white and pink flies ensued after the rains. Despite applying pesticides every week, he couldn't salvage the crop.

Consequently, his production per acre dwindled to a mere five maunds.

Ibad conveys that the cotton crop has posed persistent challenges for him in recent years, primarily due to the unavailability of standard seeds. Dr Jahanzeb acknowledges that, to date, there is a deficiency of seeds in Pakistan capable of withstanding such climatic extremes. According to him, exhausted farmers in various regions have opted to cultivate alternative crops instead of cotton.

In places like Vehari, Khanewal, and Sahiwal, a significant portion of the cotton area has shifted to maize, while in some areas, farmers are now prioritising sesame cultivation. According to the Department of Agriculture, in 2001, the Vehari district, once dubbed the 'Cotton King,' had cotton cultivated on six lakh 40 thousand acres, which by 2022 had dwindled to a mere 115,000 acres.

Conversely, in 2001, corn occupied an area of only 26 thousand acres in Vehari district, but in 2022, its cultivation area surged to 6 lakh 57 thousand acres.

Similarly, in recent years, the sesame cultivation area in Punjab has witnessed an uptick. Last year, sesame was sown on 9 lakh 30 thousand acres in Punjab, marking the highest in the history of Pakistan, akin to the trend observed for mustard.

According to Saim, the increasing inclination towards mustard over wheat and sesame over cotton is a farmer's choice. This shift stems from their losses in cultivating these two traditional crops over the years.

In his view, countries worldwide, including China and India, grapple with the challenges of climate change. However, they have developed cotton and wheat seeds that can endure adverse weather conditions or have shorter crop periods. He says that all government institutions in Pakistan seem to be inactive on this front.

He provides an example of cotton farmers who cultivate the crop earlier in Pakistan, specifically in February or March, experiencing more lucrative returns. This timing allows the crop to be harvested in July-August before the onset of harsh temperatures and rains.

The underlying rationale for the increasing popularity of mustard and sesame lies in the fact that both these crops have a short maturation period of three to four months. As a result, they are less susceptible to the adverse impact of harsh or cold weather.

Challenges of rainfall disparity and drought conditions

Muhammad Mohsin Khan, a resident of Sarai Naurang Tehsil in Lakki Marwat District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, cultivated chickpeas on his 150 acres of rainfed and sandy land until two years ago. However, he has since abandoned chickpea cultivation. Notably, he sold his sandy land and acquired 50 acres suitable for cultivating wheat, vegetables, and paddy crops.

He explains that currently, his area experiences no rainfall from December to April, making it unsuitable for chickpea cultivation.

In Lakki Marwat, a significant shift is observed among farmers like Mohsin, with a majority discontinuing the cultivation of chickpeas. Over the past eight years, the area under chickpea cultivation in this district has diminished by 53 per cent.

According to provincial agriculture department data in 2014, chickpeas were cultivated across 41,716 acres in Lakki Marwat district. However, by 2022, this figure has dwindled significantly to 17,008 acres. This trend is not unique to Lakki Marwat, as the entire province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has witnessed a 55 per cent reduction in the cultivation area over these eight years.

A farmer named Rahimullah Khan, who also serves as the chairman of a local farmers' organisation, notes that climate change impacts all crops in his area, including wheat, Maize, vegetables, melons, and watermelons. He expresses concern: "In the past few years, the corn and melon crops in our region have also been affected by severe weather."

In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the area under chickpea cultivation is dwindling due to heavy rains. Conversely, in the Thal desert of Punjab, which contributes to 75 per cent of the country's chickpea production, there has been an 18 per cent decrease in chickpea cultivation due to reduced rainfall.

Furthermore, across Pakistan, the area under cultivation for lentils has plummeted by 70 per cent, and that of mung beans has decreased by 30 per cent. These three pulses are typically grown in the rainfed areas of Pakistan.

The impact of climate change has been so profound that Pakistan, once self-sufficient in pulses as of 2010, is now compelled to spend 28-29 crore rupees daily to fulfil its pulse requirements.

According to the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP), Pakistan may lose 9 per cent of its annual GDP due to climate change. These impacts on agriculture increase the risk of extreme poverty, pose threats to food security, and contribute to malnutrition in the country. Such challenges make progress in poverty reduction and human development significantly more daunting than current circumstances. Pakistan, already ranked 92 out of 116 countries on the Global Hunger Index in 2021, is likely to experience a further deterioration in its situation in the coming years. Without timely measures to address food insecurity and adapt to the adverse effects of climate change, the very survival of Pakistan could be at risk.