Gendered struggle for equality in the shadows of climate crisis

By Shmyla Khan | Posted On : Dec 20,2023.

From massive floods every few years to urban flooding in metropolises such as Karachi, droughts to heatwaves in Balochistan and Sindh rendering some regions uninhabitable–Pakistan is one of the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world. This vulnerability, however, is not experienced uniformly. Women and gender minorities are more susceptible to the harms of climate change, harms that are compounded by intersectional factors such as class, location, caste, religious status and disability. Climate change exacerbates existing inequalities within society, and patriarchal structures inevitably inform how climate risks play out. Gender-based violence is prevalent and under-reported throughout Pakistan– a country that stands 145 out of 146 countries on the World Economic Forum's 2022 Global Gender Gap Index. It is common wisdom that climate-related stressors will serve to compound these inequalities. However, how gender intersects with climate change is highly complex and context-specific.

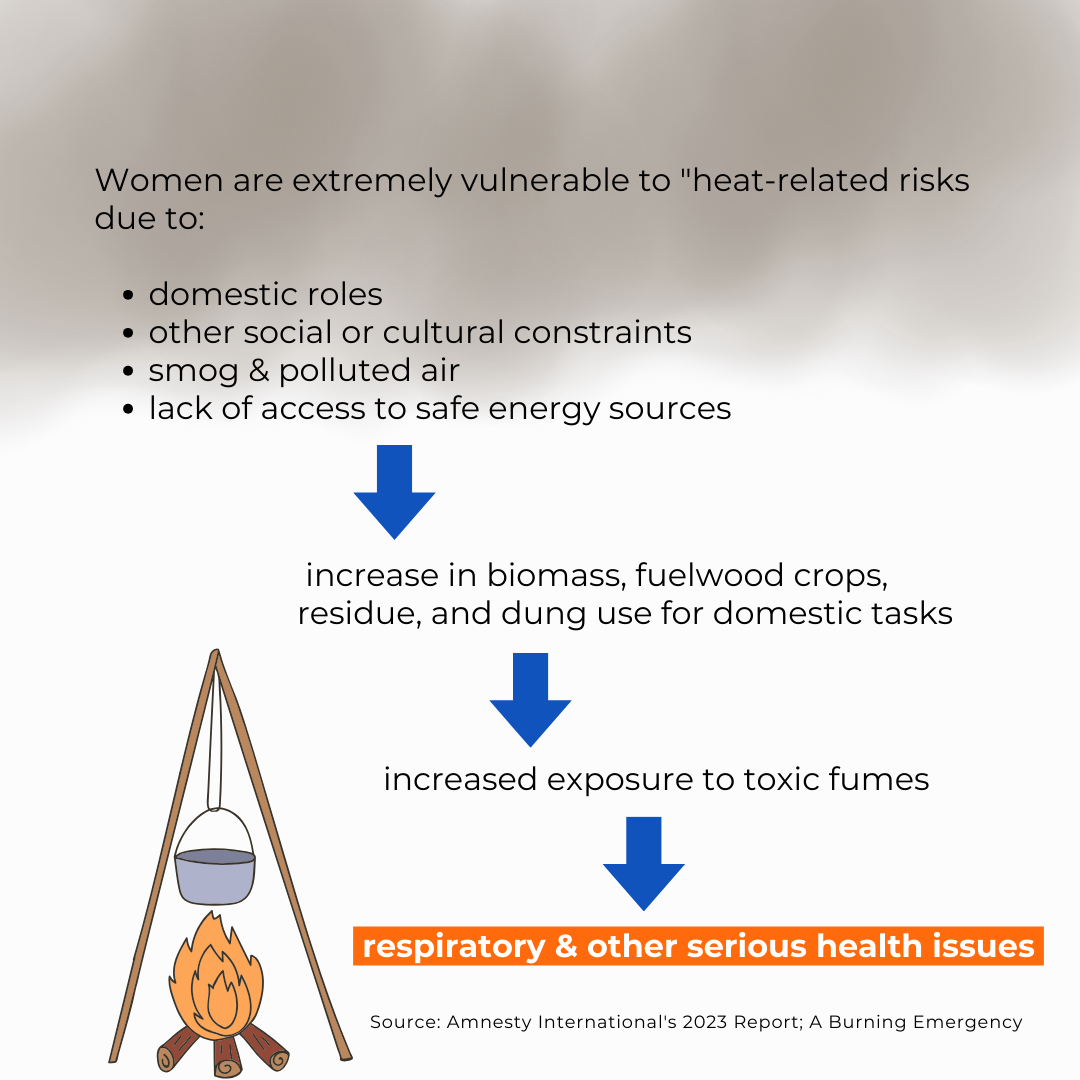

Women's health is severely impacted due to climate change and in the wake of climate disasters such as floods. Amnesty International's 2023 report 'A burning emergency: Extreme heat and the right to health in Pakistan', noted that women and girls, particularly those living in informal settlements, were extremely vulnerable to "heat-related risks because of their domestic roles and because of safety concerns and other social or cultural constraints on their behaviour." Issues such as smog and dangerously polluted air conditions prevailing across the country are exasperating for women who lack access to safe energy sources and end up using biomass, fuelwood crops, residue, and dung for domestic tasks such as cooking, which expose them to toxic fumes which add to issues in women's respiratory health.

Maryam Jamali, a grassroots organiser and researcher who runs an organisation called 'Madat Balochistan', noted that climate disaster management plans and immediate relief is often conceptualised from a "gender neutral" lens that fails to account for the specific needs of women. During the 2022 floods, she saw that "a lot of the aid that came failed to consider gender dynamics; for instance, in many areas, only male doctors were sent, which meant that women could not go to them because of cultural values in many areas." Maryam highlighted that very little attention was paid to ensuring the presence of midwives or providing medicines for pregnant women in climate-affected areas. Most experts believe that women impacted by climate disasters are vulnerable to gender-based violence, just as such violence is a perennial part of their everyday lives. Tooba Syed, a researcher and organiser in Islamabad, noted that women displaced due to climate disasters are forced to negotiate safety and privacy while performing everyday tasks such as having to share a toilet with dozens of people in their vicinity. Maryam, while highlighting that gender-based violence is an issue during climate disasters, challenges the "sensationalist framing" that forces us to ignore the indignities and structural violence that these women face. The issue of early child marriages in flood-affected areas is also seen through this sensationalist framing rather than a product of existing gender norms and harsh economic realities in the wake of climate disaster.

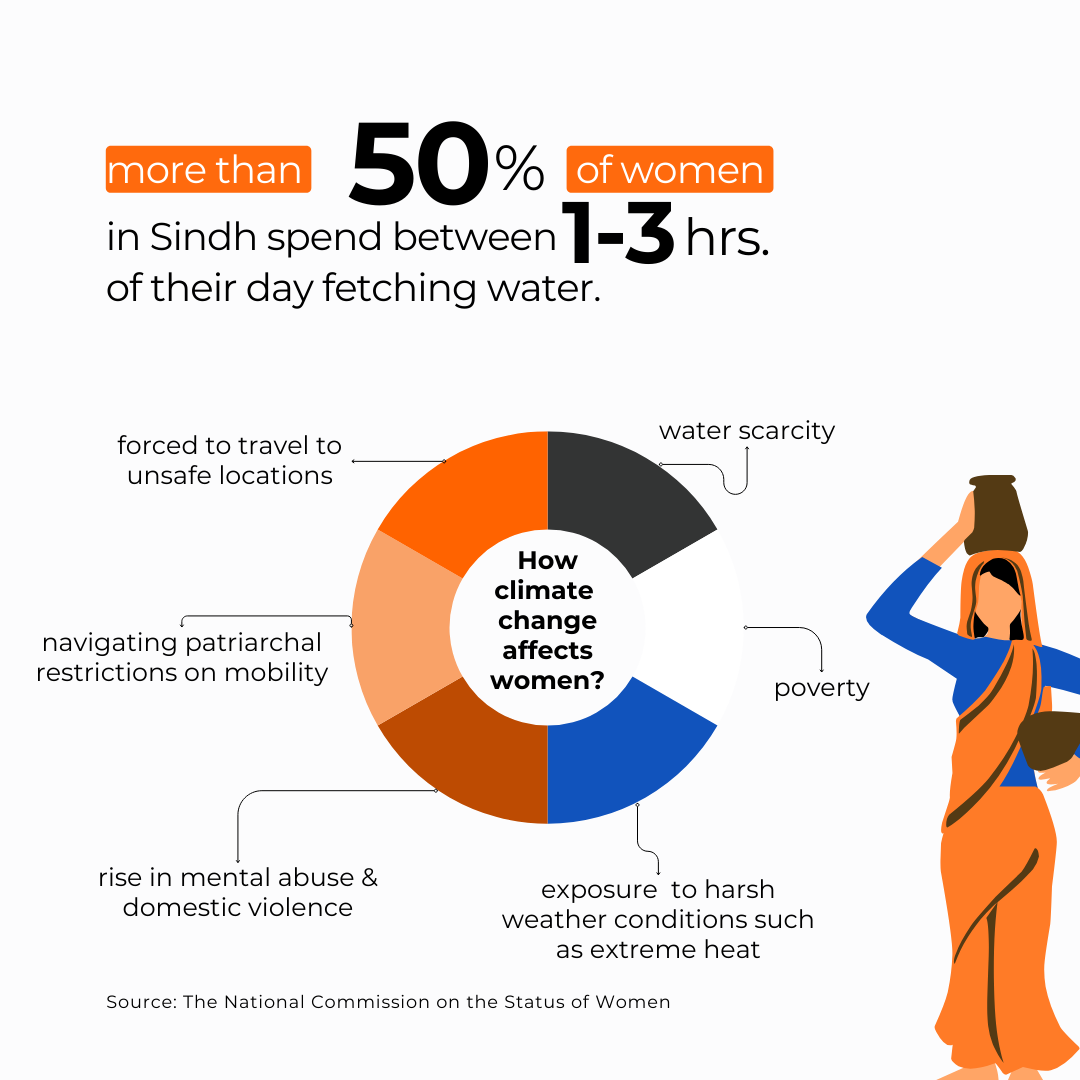

Risks stemming from climate change impact women in a myriad of ways as they are more likely to be responsible for providing food and sanitation within households. In contexts where safe drinking water is not readily accessible, women are disproportionately burdened with ensuring water supply for the family. Research in informal settlements in Karachi has shown that this results in gendered risks and insecurity as women are forced to travel to unsafe locations to procure water and navigate patriarchal restrictions on mobility. The research also found that in times of water scarcity, mental abuse and domestic violence rise. The National Commission on the Status of Women (NCSW) has found that more than 50 per cent of women in Sindh spend between 1 to 3 hours of their day fetching water, which exposes them to harsh weather conditions such as extreme heat and results in time poverty.

Extreme heat in Shikarpur District, Sindh, resulted in worsened maternal health and high rates of deaths of mothers and newborns, according to a report by White Ribbon Alliance. It also noted that despite these vulnerabilities, the government has not included maternal health in its climate adaptation plans. Gendered roles often mean that women are burdened with caregiving duties in the wake of climate change-related disasters. During relief work in Balochistan through her organisation' Mahwari Justice' in the 2022 floods, Bushra Mahnoor, a periods rights activist hailing from Attock, observed that when families were forced to evacuate, women were often the last to leave: "Women were tasked with carrying children and essential items with them, while men only had to care for themselves." Additionally, patriarchal norms played out in the uneven distribution of disaster relief; Bushra shared that "we often see that men are the first to eat in households, so when aid was given out, men's nutritional needs were prioritised, and women ended up getting very little."

Further, Bushra points out that relief given to women during climate change disasters often misses the mark because of an inherent power dynamic in how relief and disaster management plays out, "there is a tendency to talk over those affected by climate change. We must remember that we are standing in solidarity with [these women] rather than providing charity and asking them what they need." Tooba, concurs, highlighting that women are primarily seen as "victims rather than active agents within climate change." Similarly, Maryam noted that climate change strategies accounting for gender imagine women as a monolith: "There is a tendency to assume what women experiencing climate change want and decisions are taken on their behalf rather than including their opinions and recognising women have diverse opinions based on their varied experiences." In their research on 'Vulnerabilities and resilience of local women towards climate change in the Indus basin', Saqib Shakeel Abbasi et al. found that experiences of women in upper, mid and downstream areas were vastly different with varying cultural norms and degrees of participation in decision-making. It emerges that experiences of climate change are informed by gender as well as geographical, cultural and historical context. Nirmal Riaz and Muhammad Arsam, Senior Research Associates at Karachi Urban Lab, argue for "specific, space-based [climate change] policies and interventions that consider historical and structural exclusions."

Women face structural exclusions from decision-making regarding climate change at the national, provincial, and community levels. Ayesha Qaisrani and Samavia Batool point out in their research that while women are active in farming activities and agriculture, their participation in climate-related decision-making is minimal. Tooba notes that the inclusion of women in climate mitigation interventions cannot be meaningfully addressed without larger structural interventions that draw linkages between climate change and women's unequal access to land. In her work with landless female farmers in South Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Tooba noted that "women rarely own the land that they work on and in cases where men in the family have ownership, women have very little say in what is grown."

Food insecurity in Pakistani woman

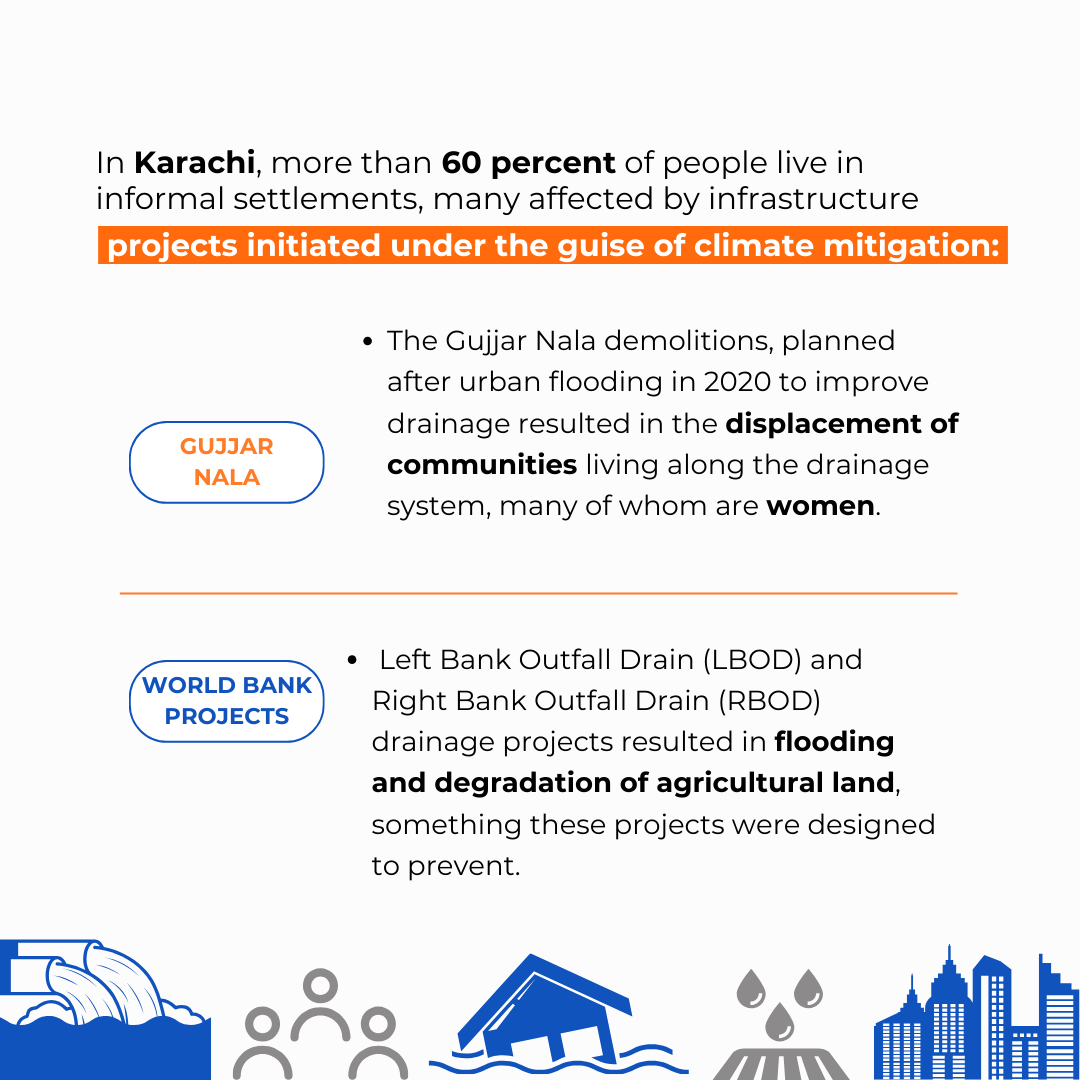

Maryam points out that climate change is also used as a "convenient excuse by the state to evade accountability for infrastructural lapses that result in more harm from climate change." Nirmal agrees that the state "cannot address climate change without taking into account the unique identities of people who have been impacted and living with infrastructural violence. Most of these people are already from marginalised communities and unless the issue of climate is connected to the issue of basic infrastructure and amenities, it will fail to address the issues women face." The need for context-specific and participatory climate mitigation is urgent not just to prevent "gender blind" interventions but to guard against interventions found to be extremely harmful to marginalised communities, particularly women. Nirmal and Arsam state that marginality in the context of climate change comes in many different forms, "while climate change impacts everyone, it impacts marginalised communities in very different ways. In Karachi, where more than 60 per cent people live in informal settlements, many have been affected by infrastructure projects initiated under the guise of climate mitigation, such as cleaning of the Gujjar Nala." The Gujjar Nala demolitions, planned after urban flooding in the city in 2020 to improve drainage in the city, resulted in the displacement of communities living along the drainage system, many of whom are women. Local activists also raise concerns regarding top-down approaches taken by both the state and aid-dispensing bodies such as the World Bank. For instance, Left Bank Outfall Drain (LBOD) and Right Bank Outfall Drain (RBOD) drainage projects, both funded by the World Bank, have resulted in flooding and degradation of agricultural land, something these projects were designed to prevent. Connections have also been made between the World Bank-funded SWEEP project and the demolitions by the Karachi city authorities at Gujjar Nala.

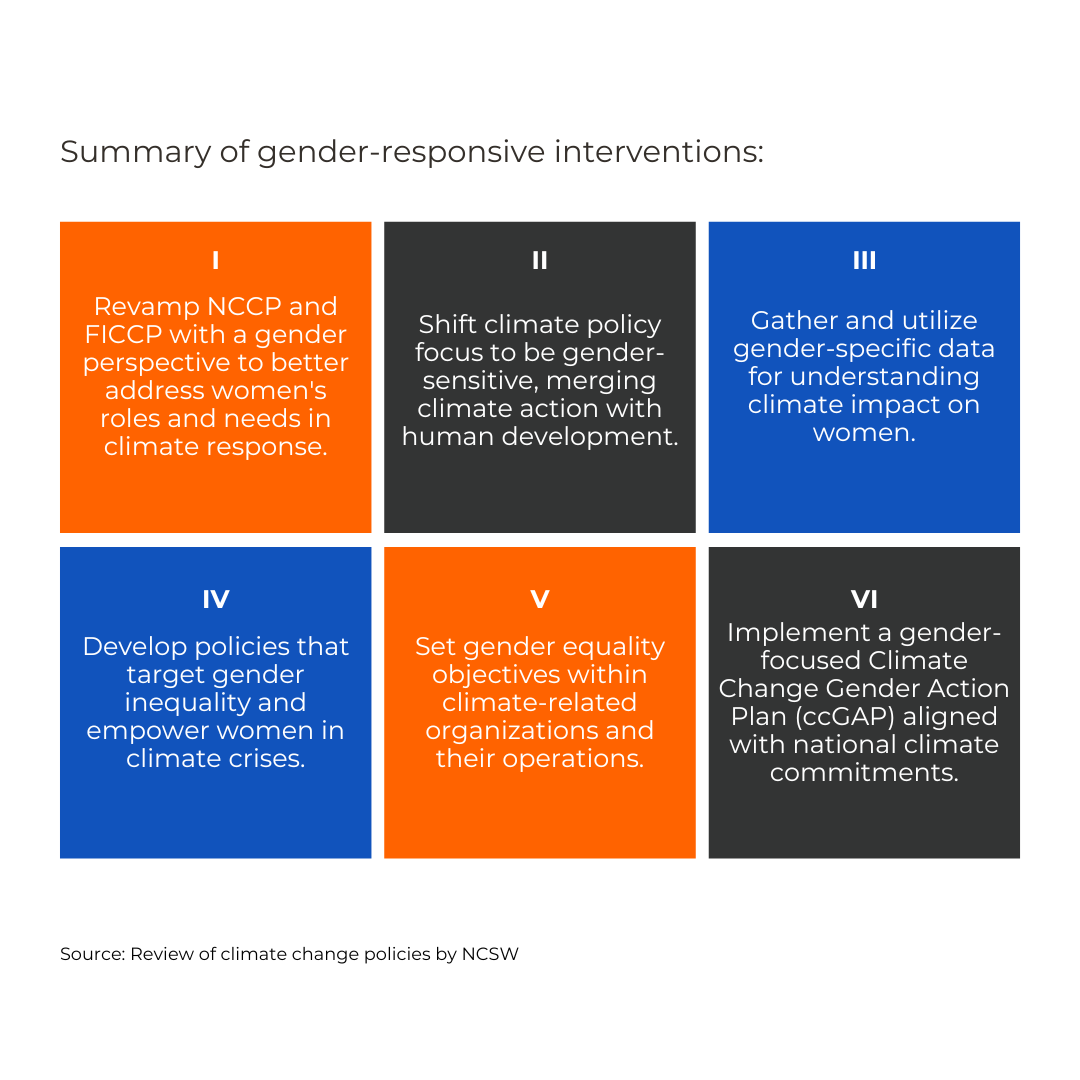

Interventions by the state are marked by a patchwork of policies, often overlapping and creating parallel structures to existing ones. Nirmal, drawing on her experience of engaging with policy work on climate change, points out that "many of these policies are not addressing the more complicated, contextual issues that we see in Pakistan." While the 'National Adoption Plan 2023' includes recommendations for greater gender inclusion, these plans have yet to translate into the inclusion of women bearing the brunt of climate change. In its review of climate change policies, the NCSW notes that while major policies such as the 'National Climate Change Policy', 'National Water Policy' and the 'National Disaster Response Plan' mention gender and include gender-responsive interventions (except for the National Water Policy), these inclusions are limited and do not contain gender-disaggregated data.

Climate change policymaking needs to start seeing women as active participants in climate mitigation rather than passive recipients. Tooba urges the need for more funding for indigenous, riverine and fisherfolk communities to come together in meaningful ways to talk about solutions: "Many women have already developed heirloom practices because of their unique relationship with the land that allows them to see patterns of climate change before anyone else–these are practices we need to build on rather than introduce top-down interventions."

Maryam and Bushara, both young climate change organisers, see conversations around gender and climate change as far removed from the lived realities of the women who bear the brunt of its harms. Bushra points out that "high-level conversations resort to appointing spokespersons for impacted communities, creating gatekeepers and excluding those impacted." For Maryam, policy forums such as COP are highly inaccessible, "these discussions do very little to change the realities that women experience. I have long let go of the expectation that we will get a seat at the table."