By Kiyya Baloch

On a cold December evening in Pakistan's capital, a tented camp was set up in freezing temperatures outside the National Press Club.

Older men, women, teenagers, young girls, and boys were all sitting there. At first glance, it could be mistaken for a temporary shelter set up in Kashmir or Gaza by people fleeing the horror of war.

Instead, citizens from across the nation found that this was a camp set up by Baloch people who had travelled for more than a week to arrive in Islamabad and protest against what they term "enforced disappearances."

Photograph by Fatima Razzaq

Promptly, this tiny camp was surrounded by geared police and encircled with barbed wire. Resembling a highly sensitive area where security installations are stored, or high-profiled people are seeking protection, the area instead hosted primarily young, poor women. Inside the camp, photos of more than a hundred abducted and missing civilians were displayed. Among them were doctors, students, teachers, and even personnel of law enforcement agencies like the Balochistan police.

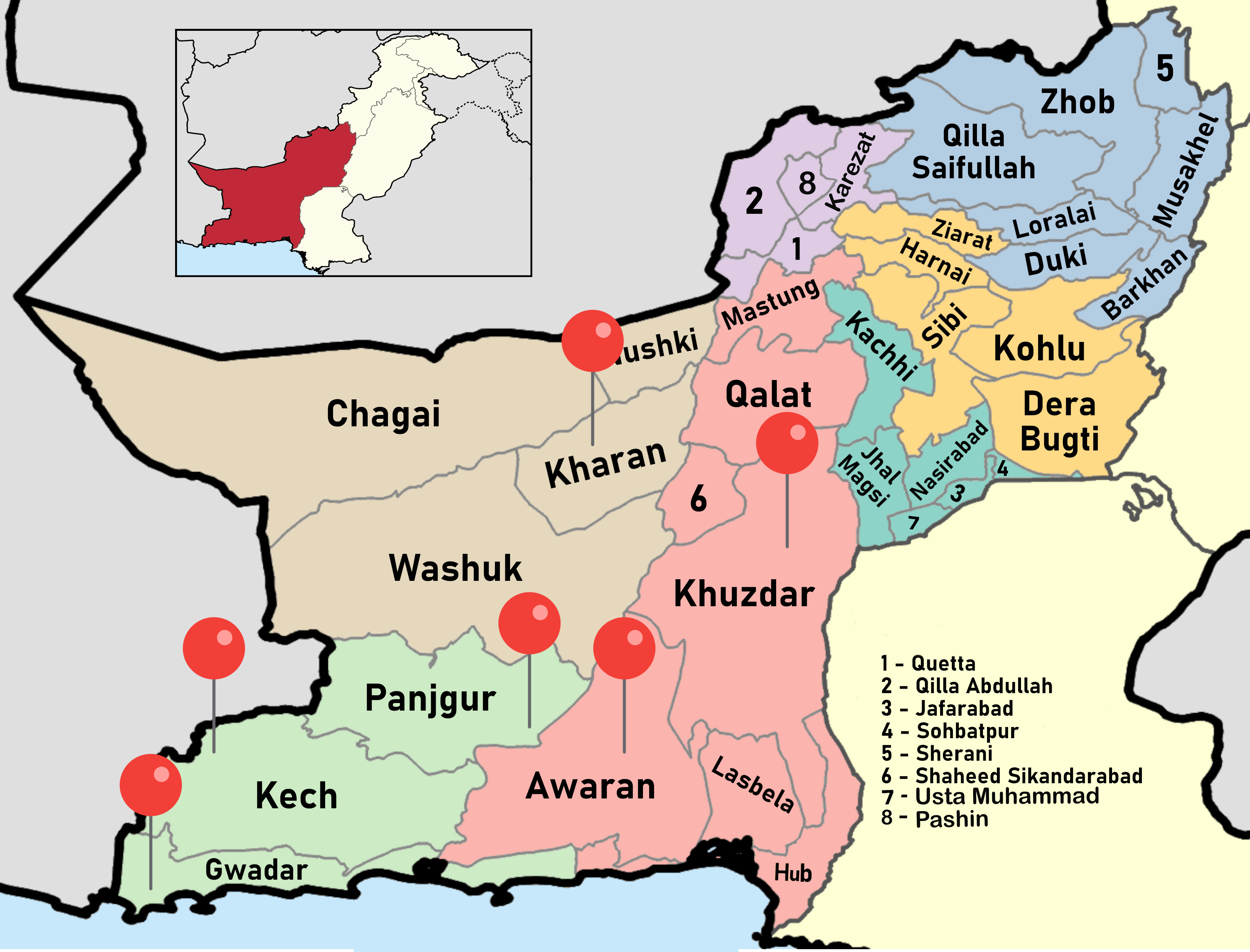

Balochistan, Pakistan's troubled southwestern province, has become a place where death and destruction are all too common. A violent separatist insurgency that broke in the early 2000s has resulted in the deaths of thousands of civilians and law enforcement personnel. Since then, Balochistan has been gripped by chaos and instability while law enforcement agencies struggle to crush a rebellion that has sustained for over 20 years.

During counterinsurgency operations, thousands have allegedly been forcefully disappeared by security forces, a charge that the country's security agencies strongly refute. It appears that the worst affected by enforced disappearances are young women who have grown up protesting on roads, streets, and outside press clubs. Lok Sujag spoke to a few young Baloch women from various districts of Balochistan who have been protesting for years in a bid to find their missing loved ones amidst threats of harassment, violence, coercion, and malicious campaigns allegedly backed by state authorities.

Photograph by Fatima Razzaq

SURAB DISTRICT, BALOCHISTAN

Farzana Rodeni, 24, is one of these young women who camped outside the National Press Club in Islamabad for a month.

Photograph supplied by Interviewee

Farzana was only thirteen when her brother, Saif Ullah Rodeni, was picked up by unknown men alleged to be from powerful secret agencies on 22nd November 2013. Saif Ullah, a constable in Balochistan police, was abducted while he was visiting his ailing mother from Surab district in central Balochistan, around 200 kilometres from the provincial capital, Quetta. Since then, Farzana has been protesting for the recovery of her missing brother.

“I have been protesting for 11 years now,” she told Lok Sujag. Saif Ullah's disappearance took a heavy toll on the entire Rodeni family. Both his parents, his mother and father, passed away due to depression, and Farzana had to give up her studies as a result of financial constraints. "My mom and dad both passed away while waiting to see Saif Ullah. I was a bachelor’s student and had to give up my studies because I could not afford to continue," she said.

During 11 years of protests, Farzana witnessed various governments changing in Pakistan, with politicians from different political parties meeting her and promising to release her brother. She also participated in a two-month-long sit-in in the provincial capital's Red Zone in 2023. Along with other women, she only ended the sit-in after then Federal Interior Minister Rana Sanaullah assured them of the recovery of their loved ones. However, her missing brother never returned.

In recent years, the issue of missing persons in Balochistan has become one of the most pressing issues. The Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) government established a commission in 2011 to trace missing persons and assign responsibility to the individuals or organisations responsible for their disappearances.

"I have appeared before the missing persons commission, Joint Investigation Teams (JITs), and met politicians, and went to Islamabad, but I have only been disappointed everywhere," Farzana told Lok Sujag.

Farzana's struggle is not an isolated story. Hundreds of young women have recently taken to the streets, protesting and demanding the release of their loved ones who they say have been forcefully disappeared by security agencies.

Photograph supplied by Interviewee

Baloch women have been protesting against enforced disappearances since 2010 but the number of women participating in movements against enforced disappearances remained low in the past. Interestingly, they were not in leading positions. However, in recent years, the situation has dramatically changed.

Malik Siraj Akbar, a Baloch journalist based in Washington D.C., who edits the Baluch Hal and is the author of "The Redefined Dimensions of Baloch Nationalist Movement," recalls his time working as a journalist in Quetta in the first decade of the year 2000. Speaking to Lok Sujag Siraj said that when many mainstream political parties hesitated to use the term ‘agencies’ to define the culprits behind the missing persons issue, a Baloch female lawyer named Shakar Bibi for the first time highlighted the issue through press conferences, marches, and seminars.

Still, at that time, the number of women protesting against enforced disappearances was very low. Farzana Majeed, a graduate in Biochemistry and sister of missing Zakir Majeed, a student leader of the Baloch Students Organisation (BSO Azad), and Sammi Deen Baloch, daughter of missing General Physician Dr. Deen Muhammad, were among the first few women who protested for their loved one’s release.

British Pakistani journalist and author Mohammed Hanif wrote in a booklet, The Baloch Who Is Not Missing and Others Who Are, after Zakir was kidnapped, his sister Farzana Majeed filed a writ petition in the Balochistan High Court. She then held a press conference in the Press Club in Khuzdar, staged a protest outside the Quetta Press Club, and, in May 2010, set up a protest camp in Karachi along with the families of other missing persons.

Around then, however, there were hardly a dozen women protesting. In October 2013, Farzana, along with a dozen relatives of people, mostly men who had disappeared or been killed in restive Balochistan province, marched more than 2,000 kilometres to Islamabad to call for UN intervention.

KHUZDAR DISTRICT, BALOCHISTAN

Among many participants of this year’s Long March to Islamabad, one young lady was the 19-year-old Saira Baloch from Balochistan's Khuzdar district.

Khuzdar has witnessed the worst horrors of the Baloch conflict. In January 2014, three mass graves containing only skeletons were discovered in the town. Most of the corpses were too decomposed to be identified. Following the discovery of the mass graves, Balochistan's provincial government launched a judicial inquiry, but the inquiry commission's findings were never made public.

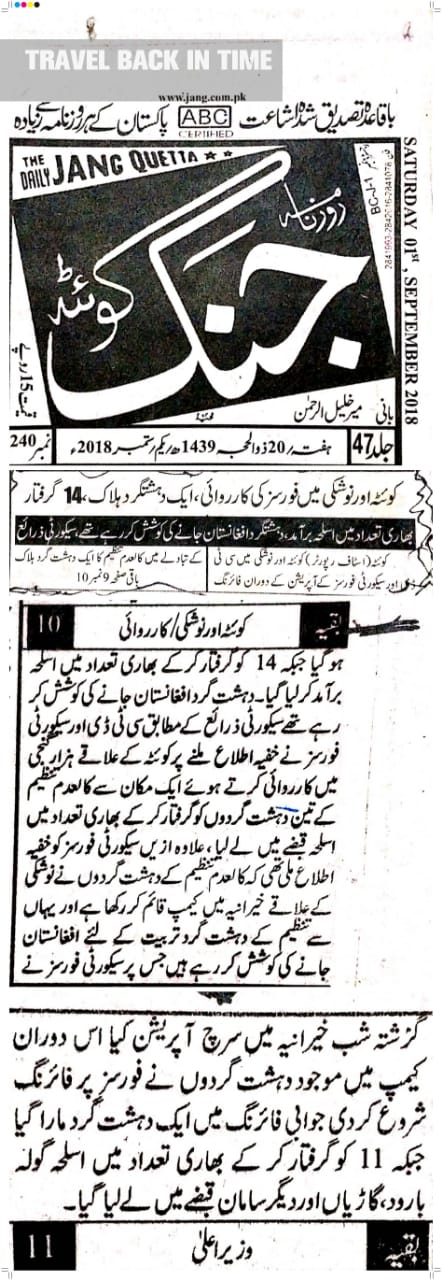

Saira's brother, Asif Baloch, and her two cousins, Rasheed Baloch and Salman Baloch, have been missing for many years now. Rasheed is also Sara's brother-in-law. Asif and Rasheed were picked up on August 31, 2018, from a popular picnic point in the Nushki district. Another cousin, Salman, was forcefully disappeared from Hazar Ganji, a suburb of Quetta, on November 13 November 2022.

Photograph supplied by Interviewee

Local media ran breaking news of Asif and Rasheed's arrest. Media reports seen by Lok Sujag claimed that law enforcement agencies had apprehended 11 terrorists during a counterinsurgency operation. Their pictures were shown on local media with hands cuffed and eyes blindfolded. But then they were never seen or heard from again. Asif was an employee of the Balochistan police.

"The world ended for us the day my brother-in-law and brother were picked up," Saira said. "We were further devastated after another cousin, Salman, disappeared in November 2022."

When Saira's brother Asif disappeared, his daughter Mahgul was only three months old. She is now six years old. The family has always kept the fact that her father is missing hidden from Gul, but Saira says she now realises something is wrong.

Photograph supplied by Interviewee

"She says everyone has fathers. Why don't I have a father? Where is my father?" Saira says in a trembling voice filled with emotions. Saira’s cousin and brother-in-law Rasheed's mother, Saira says, who passed away last Ramadan, was calling Rasheed's name minutes before her death.

"Instead of reciting Kalma, the basic Islamic belief, she was continuously calling her son Rasheed until she breathed her last," the emotionally distressed Saira told Lok Sujag.

Photograph supplied by Interviewee

GWADAR DISTRICT, BALOCHISTAN

Like Saira, dozens of other young women are participating in protests for the recovery of their loved ones. One is Sadaf Ameer, who is only 14 and the eldest child of her parents from the coastal town of Gwadar.

On August 4, 2014, just ten days before Pakistan's Independence Day, Sadaf's father, Ameer Bakhsh, was kidnapped from his home in Belar Kulanch, a cluster of villages around 50 kilometres east of Gwadar district.

She was only four years old at the time. Now 14 years old and a 10th-grade student, she has participated in the Islamabad dharna.

She does not remember anything about her father except for the day when dozens of soldiers with heavy weapons, dressed in military gear, arrived at their home, took her father away, beating him and tearing his shirt apart in the early hours of the day. Her only brother, Nuhan Ameer, remembers nothing about their father. She first came onto the streets in November 2023 after hundreds staged a sit-in in Turbat following the extrajudicial murder of a youth named Balach by the counterterrorism department.

"I want to know about my father. I want to know whether he is alive," she said.

For many years, Sadaf had hidden from her classmates the fact that her father was missing. However, when she appeared for her 9th-grade exams last year, the school required a copy of her father's national identity card. "I didn't have it, so I used my mother's card. That's when the school administration learned about it," she said.

"Now I am appearing for 10th-grade exams, and the school again requires my father's national identity card. This time, I heard my mother's card won't be accepted," the fourteen-year-old teenager says with a mixture of frustration and sadness.

The issue of missing persons in Gwadar and Makran coast came into the spotlight during the PPP's government from 2008 to 2013, although there were isolated cases even before that.

However, enforced disappearances in this tiny dusty coast became a common practice after the launch of the much-talked-about China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a bundle of projects consisting of a 3,000 KM network of roads, railway lines, energy pipelines, and fiber optic cables. The worst affected areas, where hundreds of people have been forcibly disappeared, are from the Makran coastal region, the site of Chinese infrastructure projects. The CPEC projects have been under attack by Baloch armed groups, and in retaliation, law enforcement agencies have responded by disappearing dozens of youths and alleged militants.

After disappearing, some youths were shot dead, and their bodies were thrown on deserted roads with severe torture marks and burns. Some were beyond recognition, with only a paper in their pocket bearing their name.

Gwadar district, often called the Crown Jewel of CPEC, is the gateway to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Yet, it remains one of the poorest and most affected districts by enforced disappearances, where scores of youths have disappeared, and many have been killed.

Unhappy residents of Gwadar accuse Islamabad and Beijing of plundering their natural resources, which has fuelled a violent separatist movement that has sustained for two decades. The state has reacted harshly by disappearing young voices from Gwadar that are critical to CPEC.

One of the many who have disappeared from this impoverished, dusty coast is Bolan Karim. Bolan hails from Pasni, a sub-tehsil of Gwadar.

Photography supplied by Interviewee

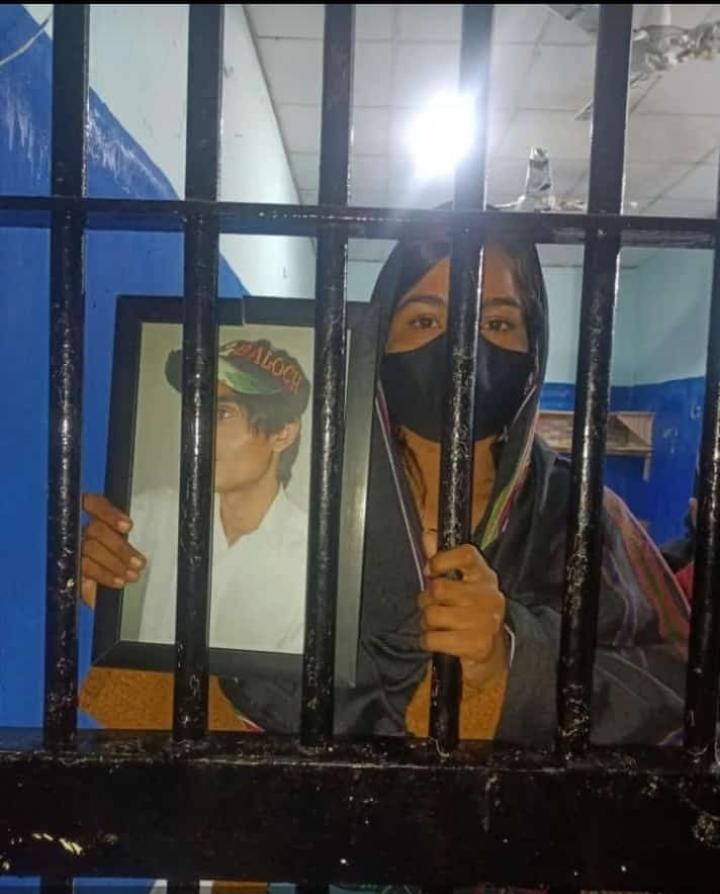

Bolan has been missing for 12 years. He was whisked away from the Pasni airport road on 4 January 2013.

When Bolan was whisked away, he was too young – hardly 17 and a student in 10th grade. His sister Hajira Karim, 18, a student in 12th grade, has been on the roads demanding the safe release of her missing brother.

"Unknown mobile phone numbers have threatened us, and people closely connected to secret agencies have visited our home, warning us to remain silent. Otherwise, my other brothers will meet the same fate," she said.

Photography supplied by Interviewee

In Balochistan, according to Dr. Mahrang Baloch, many families do not come forward to report incidents of enforced disappearances out of fear, and some are blackmailed that if they remain silent, their loved ones will be released.

Hajira says her other brother, Nudan Karim, who joined her in the Islamabad protest, was forcefully disappeared in 2017 merely for advocating for her missing brother, Bolan.

"But we are no longer afraid. Even after the Islamabad sit-in, we have been constantly threatened and harassed."

Although the missing persons issue has affected all of Balochistan, particularly its Baloch-dominated districts, mainly in southern Balochistan, and part of the problem is that the government and State authorities are reluctant to acknowledge enforced disappearances.

The caretaker Prime Minister Anwaarul Haq Kakar claimed in October and November that the number of missing persons in Balochistan is less than 50, while the then Interior Minister and Balochistan's current Chief Minister Sarfaraz Bugti mocked the families of disappeared by saying that most missing persons end up in Karachi due to domestic disputes with their spouses.

Such jokes take a heavy mental toll on the families of disappeared persons.

"It is psychological torture,” says 22-year-old Ruksana Dost from Gwadar, whose brother Azam Muhammad Dost was whisked away by agents of security agencies from a friend's shop in Gwadar 2015, “One of my sisters has become a psychiatric patient. My mother, including all my siblings, are emotionally and psychologically disturbed.”

Balochistan is plagued by anxiety, depression, and various mental illnesses and disorders due to violence, enforced disappearances, climate change, and poverty. Yet this rising mental health crisis goes untreated and unnoticed

Photograph supplied by Interviewee

Imrana Imdad, a psychologist and social worker researching the psychological impacts of climate change on mental health, says that the ongoing cycle of violence and natural disasters in Balochistan should have provided an opportunity to expand mental health services in the province. She points out that natural disasters often prompt significant humanitarian responses. However, she laments the lack of attention paid to addressing the mental health issues faced by Balochistan.

According to Imdad, mental health care services are virtually nonexistent in Balochistan. This deficiency affects not only the families of missing persons, who survive years of anguish, but also victims of violence, terrorism, and natural disasters.

"There is a severe lack of mental health support in Balochistan despite the pressing need," said Psychologist Imdad.

According to Psychologist Imdad, in 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched a pilot implementation of the Mental Health Gap guidelines in select districts across each province in Pakistan. However, apart from the initial launch, there has been no progress.

"Despite Balochistan facing a mental health crisis exacerbated by violence, natural disasters, and climate issues, there is zero attention to it," adds Imdad.

Mentally distressed Ruksana recently joined a month-long sit-in in Islamabad to urge authorities to find her missing brother so that the poor family could find some mental relief.

Local Baloch rights groups claim that over the past two decades, more than 8000 people have vanished from Balochistan without any trace. The government and its commission constantly dispute this figure.

According to Pakistan’s Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances, at least 2,708 people were reported missing in Balochistan from 2011, when the commission was established, until August of last year. The commission claims it resolved the cases of over 2,250 individuals, claiming they either returned home or were found in internment centers or prisons.

In 2018, Akhtar Mengal, the leader of the Baloch ethno-nationalist Balochistan National Party Mengal (BNP-M), presented the government of Imran Khan with a list of 5,000 alleged victims of enforced disappearances. However, neither enforced disappearances stopped nor were many of those listed released.

AWARAN DISTRICT, BALOCHISTAN

Considered one of Balochistan's most militarised districts and once one of its most unrestful places, Awaran has been the centre of skirmishes between armed groups and security forces.

Dr. Allah Nazar Baloch, a General Physician turned Guerrilla commander, hails from Awaran and leads the Balochistan Liberation Front (BLF), one of the deadliest ethnic-separatist militant organisations.

According to Baloch rights activists, several women have forcefully disappeared briefly, faced harassment, or been detained for hours by law enforcement agencies on suspicion of their male family members' involvement in the insurgency in this remote, undeveloped, militancy-ridden town. However, these cases often go unreported locally due to cultural shame.

"What happened to one of my aunts is more painful than death to explain," shares a Baloch woman whose aunt was allegedly detained in an FC camp in Awaran in April 2019 for more than 12 hours and coerced into calling her husband to surrender to authorities.

"Not only is it culturally shameful to talk about it, but she fears openly discussing it would ruin her future. However, she finds strength in seeing other women protesting on the streets now. She was so traumatised that she did not want to see anyone, even within the family, for months."

Last year in May, the ethno-Baloch nationalist Baloch National Movement (BNM), a pro-separatist political party with most of its leadership living in exile, claimed in a press release that Najma Dilsard, a school teacher, committed suicide after being coerced by a Levies official named Noor Bakhsh to work as an informant for secret agencies linked to the country’s powerful armed forces. When Najma's case went viral on social media, the district administration in Awaran came under pressure, dismissed the Levies official, and initiated legal action against three Levies men accused of forcing and blackmailing Najma.

Besides that, in Awaran, several women have died in their relentless wait for their missing children and loved ones to be released. One of these victims was Ganjal Baloch, 21, whose family Lok Sujag had the chance to speak to.

"My sister-in-law, Ganjal, became so traumatised that just two years after her husband's disappearance, she couldn't bear the pain and passed away," said Shaista Baloch, 19, from Awaran. She spoke of her uncle Safar Ali, the son of Qadir Baksh, who was allegedly abducted by Pakistani security forces from Hub Chowki on October 23, 2013. "Safar's father suffered a mental shock and became paralyzed, while his mother has become very weak and ill."

Shaista was part of the month-long sit-in in Islamabad.

"I have promised my family that I will fight to find my uncle," the young lady said.

Safar has no sisters, his aged parents are sick, and his wife died of stress. His niece Shaista campaigns for his release, although she says this has disturbed her studies.

KECH DISTRICT, BALOCHISTAN

Teenage girl Shams Atta Ullah is one of those who has recently broken her silence and started campaigning for the release of her brother. Shams is only sixteen years old. Her brother, Israr Atta Ullah, 17, was picked up on 12 March 2023, around 1:30 midnight, from Tump tehsil in the Kech district.

"We remained silent out of fear and with the hope that if we remained silent, my brother might be released. Our biggest fear was that if we spoke, he might be harmed. But we want answers now," said Shams.

According to Shams, a contingent of armed forces arrived at their house in the Tump area of Kech district around 1:30 am, searched the entire house, and took her 17-year-old brother Israr away with them, promising his release after two hours.

"But he never returned. We waited for months. Finally, we decided to break the silence last November, and I joined a sit-in in Turbat. From there, we went to Quetta and then Islamabad. I will not stay silent now. People won't stay silent even when their animal goes missing. We have lost a brother; how can we remain silent?"

PANJGUR DISTRICT, BALOCHISTAN

Suspected of being an insurgent, Sana Ullah Noor, 16, hailing from Balochistan's restive Panjgur district bordering Iran, disappeared without a trace a decade ago.

On April 16th, 2014, five men in plain clothes driving a double cabin Vigo picked up Sana from Panjgur. A week later, his parents received a call demanding 10 million rupees in ransom. Despite their efforts, including selling property and livestock, they could only pay 1.3 million rupees in ransom.

However, the money and their son disappeared forever, and the poor family was never contacted again by the kidnappers. The calls demanding ransom stopped.

Missing Sana’s sister revealed in conversation with Lok Sujag how in 2017, the family's hopes were briefly revived when a paramilitary Frontier Corps (FC) military officer contacted Sana's father, Noor. He visited the FC camp and met an officer who informed him that the FC had apprehended his son. The officer accused Sana of being an insurgent. At the time of his disappearance, Sana was in the midst of his 11th standard exams. However, after 2017, the family received no further information about Sana's whereabouts.

Despite exhaustive efforts, including visits to police stations and army cantonments, the family's search yielded no results. In November of the last year, Sana's younger sister, Salma Baloch, joined a sit-in from Turbat for the first time and later travelled to Islamabad in a bid to find her brother.

"My brother was barely 16 at the time, preparing for his first-year exams," said Salma, who is now 18. It has been ten years since he disappeared."

During the desperate search for Sana, Salma had to give up her studies, while her father developed heart problems and her mother suffered from severe anxiety.

"We are four sisters and four brothers with Sana. All of us have been emotionally and psychologically affected by his disappearance."

After silently struggling for Sana's release for a brief period, the family has now chosen to make their plight public. Sana's sister initiated a Twitter trend on February 27th with the hashtag #ReleaseSanaUllahNoor.

"I will now take up this fight. For too long, we remained silent, refraining even from mentioning the ransom demand, fearing that speaking out might jeopardise Sana's safety," she said.

Lok Sujag has contacted the Pakistani military media wing, more commonly known by its acronym ISPR, for a comment regarding the increasing accusations against security forces for their alleged involvement in enforced disappearances. ISPR has yet to respond to Lok Sujag’s request for a comment.

COMING TOGETHER IN ISLAMABAD

Today, protests against enforced disappearances are not only dominated by women but are also led by women.

Journalist Siraj credits Dr. Mahrang Baloch for this and says her biggest contribution is liberating her people from fear.

There are also several factors behind this and one of the key factors is that when male family members started protesting for the release of their loved ones, they were threatened or kidnapped. As a result, women had to take on the lead role.

Another factor, journalist Siraj says, is their steadfastness. The Baloch women have surpassed the Baloch male leadership in terms of the public trust they have gained. Siraj credits Mahrang Baloch for instilling a new life in the Baloch civil rights movement against enforced disappearances:

“She has taken away the fear from the public of not talking against the military and the intelligence agencies. This is something we have never seen before. These young women are not going anywhere anytime soon,” added journalist Siraj.

Kiyya Baloch is a freelance journalist and researcher covering the Baloch insurgency, political developments, and militancy in Balochistan. He has been covering Baloch conflict for national and international press since 2013.