By Hazaran Rahim Dad

On February 7th 2024, the day before Pakistan’s national General Elections, #BalochBoycottElections2024 was trending in 3rd position across the country on social media platform X (formerly Twitter).

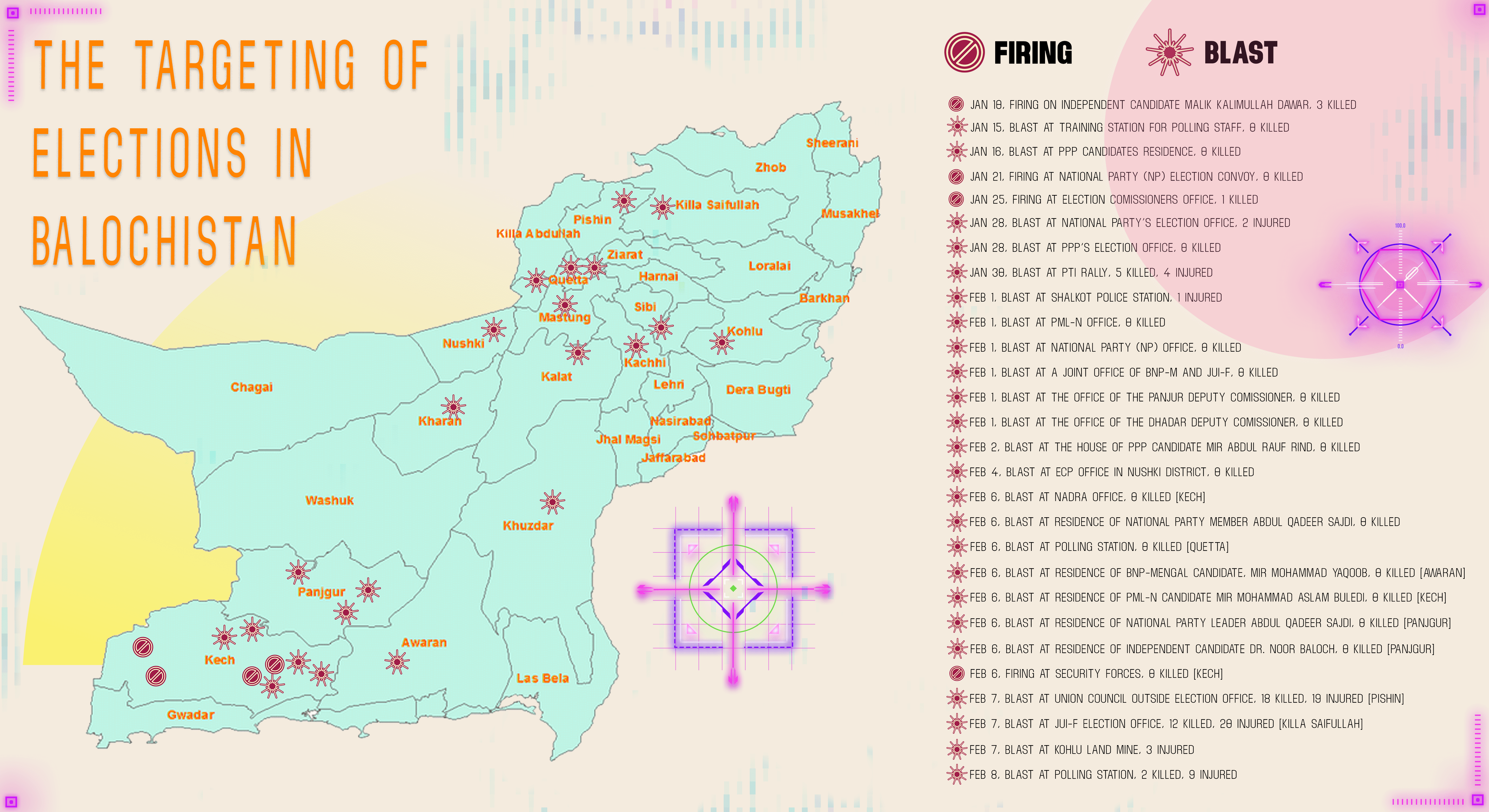

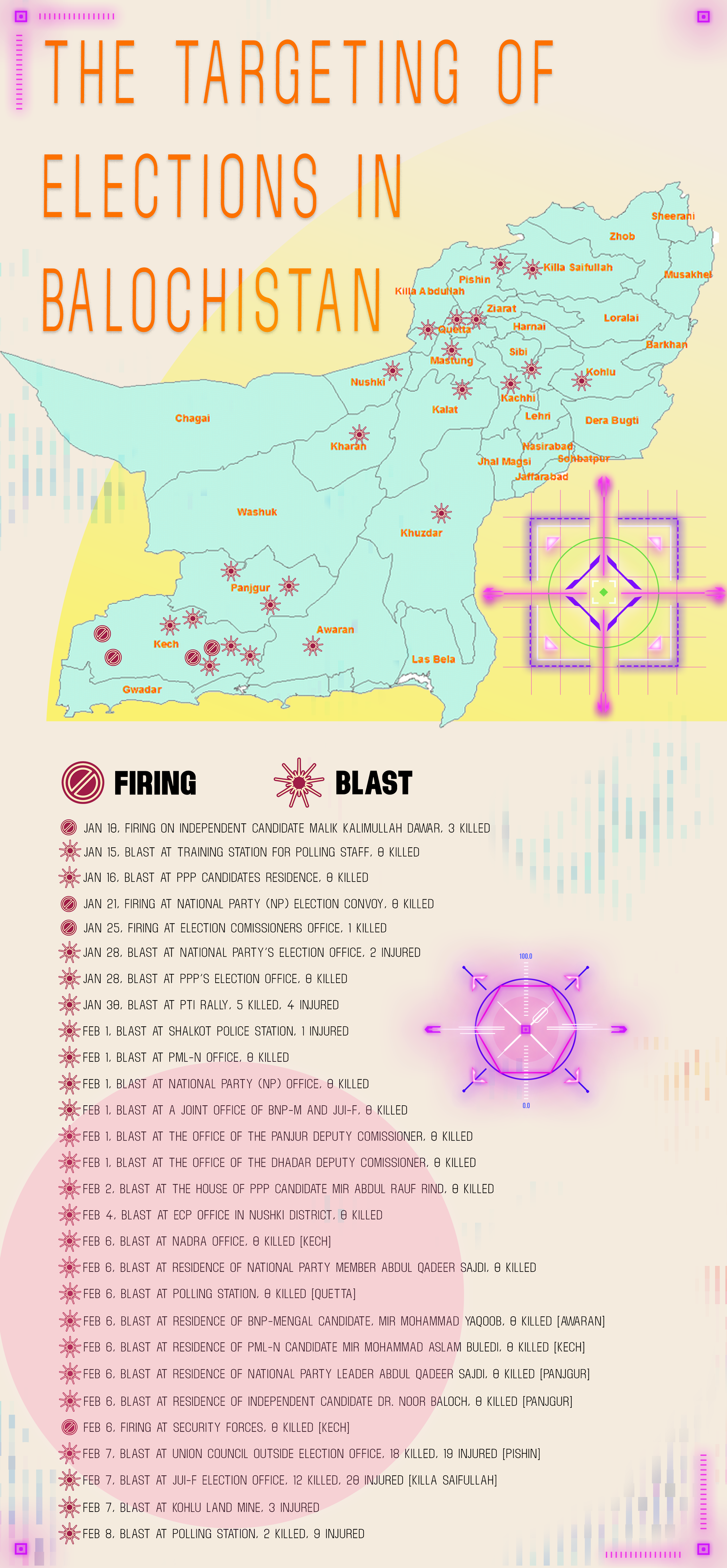

Simultaneously, The Balochistan Post reported that armed groups in Balochistan claimed responsibility for 161 attacks leading up to election day. These attacks specifically targeted Pakistani forces and election campaigns in the province – even resulting in 10 deaths and more than a dozen injuries in a blast that targeted Jamiat-e-Ulama-e-Islam’s office in Qila Saifullah in northwestern Balochistan.

On Election Day, a protest took place in the Hirronk district of Kech, where reportedly no votes were cast. In Mand, from the same district, ballot boxes were reportedly burnt by protestors.

Graphic by Ayesha Rahmi, with research support from Ahmad Abdullah

As the dust settles on Pakistan's general elections, the persistent echoes of Balochistan's struggle with the democratic system reverberate beyond the ballot boxes.

The months following up the elections, the Baloch Women's Long March in late 2023 to early 2024 brought this reality of Pakistan’s political structure and its capacity for engagement with the voices of Balochistan to the surface. Lok Sujag takes a closer look at the current tensions in the Baloch political landscape to investigate how mainstream political parties have addressed their voting concerns in the past.

“This year’s elections are supposed to be the most controversial considering the past 25 years,” expressed Rafi Ullah Kakar, a member of the Social Sector & Devolution at the Planning Commission of Pakistan, “political, nationalist and religious parties in Balochistan have shown significant concern over the transparency of these elections.”

The March Reaches Islamabad

Led by Dr. Mahrang Baloch and orchestrated by the Baloch Yakjehti Committee, the Long March from Quetta to Islamabad was greater than a protest. Welcomed to jubilating crowds in Kohlu, DG Khan, Barkhan, and Taunsa, the travelling demonstration spotlighted the grim tableau of enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings that have long plagued the province.

"It's been narrated that Baloch are violent people, they choose violence,” Dr. Sabiha Baloch, a general physician and activist with the Baloch Yakjheti committee, reflected, “but historically, peaceful struggle by the Baloch – such as Mama Qadeer Baloch’s 2014 march from Quetta to Karachi and Islamabad with families of missing – received no justice. Just like this year’s march.”

According to the BYC leader Dr. Mahrang Baloch, the camp set up at the arrival of the long march in Islamabad was visited by senior vice-president PTI Sher Afzal Khan Marwat, Senator Mushtaq, Saad Rizvi from Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan) and Farhat Ullah Babar. She also remarked with disappointment that these shows of support were limited to their visits to the camp and did not lead to any further conflict resolution.

"Each democratic party in Pakistan, during opposition or electoral campaigns, speaks of ending the practice of disappearances,” noted Sammi Deen Baloch, the Secretary-General of Voice for Baloch Missing Persons (VBMP) and the daughter of missing Dr. Deen Mohammad Baloch. “However, once in power, they often refrain from addressing this critical issue."

The Political Tapestry

Pakistan’s electoral arena in 2023 witnessed mainstream parties like the Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N) and the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) articulating renewed pledges for Balochistan's upliftment. Campaign trails were adorned with promises of addressing enforced disappearances and fostering development.

The PML-N's supreme leader visited Quetta and ended up securing the support of more than 20 electables during a visit to Quetta in November of last year.

Similarly, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari and Asif Zardari from the PPP have made several visits to Balochistan in their political preparations for this year’s election cycle.

However, the historical engagement of these parties with Balochistan's issues paints a picture of sporadic attention, raising questions about the sincerity of their electoral commitments.

“In 2018, parties like the PML N and the PPP were not on good terms with the establishment,” stated Kakar, “As a result, they formed a provincial-level party named BAP, which was temporary and not ideological. Later, the party scattered with some members joining PML N, some joining PPP, and some remaining in BAP.”

According to Kakar, this fragmentation is evident in the 2024 elections.

Preceding this shaky status quo, what has been the history of mainstream parties' engagement with Balochistan's political concerns? For this election feature, Lok Sujag delves into the state's promises to address the grievances of the people in its most resource-rich province, taking a closer look at each party's high-minded statements and subsequent conduct.

PTI: The Unfulfilled Promises

Imran Khan's Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) fell short of addressing the core issues of Balochistan during its tenure. Promises of transparency and justice were overshadowed by a perceived lack of engagement with the province's systemic issues, underscoring a pattern of neglect.

Before winning the 2018 General Elections and assuming office as the Prime Minister of Pakistan, Imran Khan, the former prime minister of Pakistan and chairman of PTI, was outspoken on the issue of Balochistan in the national discourse. In 2012, at the very dawn of his Icarean rise to political fame, Imran Khan proclaimed "that the issue of missing persons is the biggest brutality on humanity." By 2018, he was addressing the issue on Geo TV’s “Capital Talk,” hosted by renowned anchor and journalist Hamid Mir. On the show, he boldly declared that if “a single person went missing” during his government, he would stand against the security agencies.

Despite this assurance, a sit-in protest by families of missing persons from Balochistan occurred in D-Chowk, Islamabad, in 2021 during his tenure, highlighting a contrast with his earlier commitment.

Seema Baloch, sister of missing student Shabir Baloch, expressed that Imran Khan neither offered solidarity nor addressed their issue during the 2021 sit-in protest at D-Chowk, Islamabad. This stands in contrast to his previous assurances before coming to power.

However, in 2021, PTI’s human rights minister Shireen Mazari pushed for the Criminal Laws (Amendment) Act, 2021, a bill set to criminalise enforced disappearances. In February 2022, Mazari claimed that the bill itself had “gone missing” after it went to the senate

In conversation with Lok Sujag, associate professor of political economy at Quaid-i-Azam University Aasim Sajjad Akhtar noted that this was an ordinary development:

“It was not a very robust bill so it cannot be said that it attempted to totally criminalise enforced disappearances and if even such a lacklustre bill is blocked, it is a reflection of the impunity with which the state and its secret agencies operate,” Aasim added.

PML-N: A Legacy of Promises

Under the leadership of Nawaz Sharif, PML-N's tenure showcased a series of pledges aimed at resolving the province's crises. Despite launching development projects and asserting a stance against enforced disappearances, the party's efforts often dissipated into the political ether, leaving little impact on the ground realities of Balochistan.

The party boasts a history of heavy-handed statements. In 2012, Nawaz Sharif pledged to introduce a resolution in the National Assembly supporting the missing persons' case. Describing PML-N’s cause as a "jihad," Sharif asserted a commitment to persist until the missing persons are recovered.

Only a year later, Mama Qadeer led the historic 2013 Long March with the Voice of Missing Baloch Persons (VMBP) during PML-N’s time in power. Commencing on October 27th, 2013, from Quetta to Karachi first and ultimately towards Islamabad, the march aimed to raise awareness about human rights violations in Balochistan and to demand the recovery of Baloch missing persons subjected to enforced disappearances.

In a conversation with Lok Sujag, Mama Qadeer mentioned that when their long march entered the Punjab region, they encountered numerous challenges. He expressed that their march was largely ignored by the government of PML-N.

In 2014, mass graves were discovered in Tootak, Khuzdar. State response was inconclusive at best: while a commission was indeed established, it ultimately failed to provide any solutions to the issue.

During Imran Khan’s 2018-2022 time as Prime Minister, Maryam Nawaz made an appearance in Baloch attire at the 2020 Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM) Jalsa in Quetta where she made an enthralling promise to the Baloch missing persons’ families that in their government:

“No Baloch daughter would be left crying on the roads.”

In 2021, PML-N Vice President Maryam Nawaz joined the sit-in protest of Baloch missing person families.

“Come talk to them,” she urged the army chief and the head of ISI, “resolve the issues that can be solved. Produce the people who are alive in courts and those who are not [alive], at least tell the families about their status.'"

She demonstrated her commitment further by changing her social media profile picture, featuring her embracing a Baloch girl from a missing person's family.

This serves the role of a “photo-op” for a politician like Maryam Nawaz, according to Professor Akhtar, who believes that politicians use the issue of enforced disappearances while campaigning only to remain silent once in power:

“It’s a combination of opportunism and fear.”

After PDM successfully culminated in the “vote of no-confidence” against Imran Khan’s tenure as Prime Minister, PML-N leader Shehbaz Sharif visited Balochistan for the inauguration of the Quetta-Karachi highway. In his new role as Prime Minister, Shehbaz Sharif pledged to raise the issue of missing persons with “powerful quarters.”

Shehbaz Sharif denoted that development in Balochistan was a high-priority area for his government.

It remains to be seen how PML-N addresses the grievances of the Baloch masses in its current tenure in parliament.

PPP: Symbolic Gestures, Elusive Change

The PPP, with its rich history of championing human rights, has periodically voiced support for Balochistan's grievances. Bilawal Bhutto Zardari's campaign speeches frequently highlighted the party's commitment to ending the plight of enforced disappearances. Yet, the disconnect between rhetoric and action has been glaring, as tangible progress remains elusive.

The Balochistan Package, launched by the PPP leadership in 2009, included measures like a judicial commission and fact-finding missions to investigate the killings of Nawab Akbar Bugti, Ghulam Mohammad, and his two companions, as well as the immediate tracing and release of political prisoners. The package, titled “Aghaz-e-Haqooq-e-Balochistan”, is regarded as the first time the state recognized the need for “reform” in its policy towards Balochistan. It went as far as to propose the “launch of political dialogue with Baloch dissidents.”

In 2011, a 38-page progress report prepared by the Establishment Division noted that the government had implemented only 15 of the 61 proposals made in the package.

“If I become the Prime Minister, the people of Balochistan will know that their representative, their brother and son is sitting in the Prime Minister’s House,” declared PPP Chairman Bilawal Bhutto Zardari in his 2024 Election Campaign, “I will explain to them that the federation cannot run like this. I am sad that the way the caretaker government engaged the protesters in Islamabad was undemocratic.”

In conversation with Lok Sujag, Dr. Mahrang Baloch criticises the candidates the PPP has fielded in Balochistan:

"Interestingly, current PPP candidates in Balochistan are Sarfaraz Bugti and Jamal Raeesani, who function the Death Squads in Balochistan and often dismiss the missing person problem as fake. This raises concerns about how effectively Bilawal Bhutto can address and resolve the issue if elected.”

Mahrang is referring to Sarfaraz Bugti’s appearance on Aaj TV where he shows indifference towards Baloch enforced disappearances by saying that “families of those who quarrel with their wives should file a case.” Similarly, Jamal Raessani responded to an interviewer in January 2024 to state: “Missing persons [are] not a serious issue.”

Historical Context

The narrative of Balochistan's struggle is not new. The 2013 Long March and subsequent protests have consistently used peaceful resistance as a means to bring the issue of enforced disappearances to national attention. Yet, the engagement of mainstream political parties with these protests has often been fleeting, limited to electoral cycles, and lacking in substantive action.

Parties and institutions have historically resorted to powerful slogans to navigate their way into power. In Balochistan, the predominant issue of missing persons is used as a central theme of political campaigns.

Community worker and Baloch activist Sebghat Abdul Haq relates:

"For the last two decades, the province is battling human rights violations but the political parties have employed the slogan of Balochistan just to garner support during election campaigns.”

In 2006, the killing of Akbar Khan Bugti led parliamentary parties to boycott the 2008 General Elections. However, PPP secured 15 seats and formed a government alongside PML-Q and Jamiat e Ulema Islam (F). In 2008, President Asif Ali Zardari (PPP) formally apologised to the people of Balochistan for the past injustices committed against them. Taha Siddique writes in his investigative news feature, How Pakistan Army Runs Death Squads in Balochistan, that death squads were formed in the same year under the supervision of infamous mercenary leader Shafiq Mengal. Mengal joined PPP in late 2023.

During PPP’s 2008 government, enforced disappearances resurfaced when prominent Baloch political leader Ghulam Muhammad, along with his two companions, was subject first to enforced disappearance to be later killed. Similarly, in June 2009 Baloch student leader Zakir Majeed was forcibly disappeared. He remains missing till date. His mother joined this year’s Baloch Women’s Long March in Islamabad.

“At least 249 Baloch activists, teachers, journalists and lawyers have disappeared or been murdered between 24 October 2010 and 10 September 2011 alone,” reported Amnesty International in 2012, “many in so-called ‘kill and dump’ operations.”

In the face of Balochistan's long-standing grievances, every political party has acknowledged that past governments have ignored the plight of the Baloch people and their suffering. From Imran Khan to Nawaz Sharif and Bilawal Bhutto, as well as Balochistan provincial politicians such as Akhtar Mengal and Dr. Malik, all have employed a slogan against enforced disappearances to garner support during election campaigns.

Pakistani politics has often earned the moniker of functioning as a “controlled democracy.” In 2017, Awami National Party leader Afrasiab Khattak spoke at a seminar for democracy held at the National Press Club:

“Politicians in Pakistan don’t even have the capacity to properly rig elections; they have to rely on the agencies for that. This is how helpless political parties seem to be in front of the military establishment.”

In a conversation with Lok Sujag, Kakar elaborates that the general electoral trends in Balochistan differ greatly between Central Balochistan where the Sardari system is intact and Southern Balochistan (including the Makran Belt). In the former, there is no robust competition and elections follow the logic of patronage: local populations vote for Sardars who are able to mobilise access to state resources.

“Electables respond to this need by staying on good terms with each passing government,” explains Kakar.

Contrastingly, Southern Balochistan has “more competitive politics with lesser domination of elites.” The relationship with Islamabad matters a lot in the urban centres of these electoral grounds, relates Kakar.

Beyond Electoral Promises

The sit-in protest in Islamabad, lasting over two months, epitomised a mass democratic engagement with the state from Balochistan. The government’s response (or lack thereof) is already metastasizing into further political consciousness

"The Baloch were facing the worst oppression before the elections and continue to face the same oppression after the elections," reflected Dr. Mahrang Baloch as election fever settled down.

The 2024 General Elections were marked by widespread protests and boycott across Balochistan due to ongoing grievances. To an extent, it can be concluded that the Baloch community of Balochistan province boycotted this election cycle. Rafi Ullah Kakar asserts that the missing persons issue will remain significant to politics in Balochistan. He warns:

“If they try to use power to suppress this movement, it will only get stronger.”

As Pakistan moves beyond the electoral excitement, the story of the Baloch Women's Long March serves as a sobering reminder of the unresolved challenges in Balochistan.

Hazaran Rahim Dad is a Balochistan-based writer and MPhil Scholar in English Literature. She writes on fishermen rights, sociopolitical issues, art and literature.