By Khurram Ali

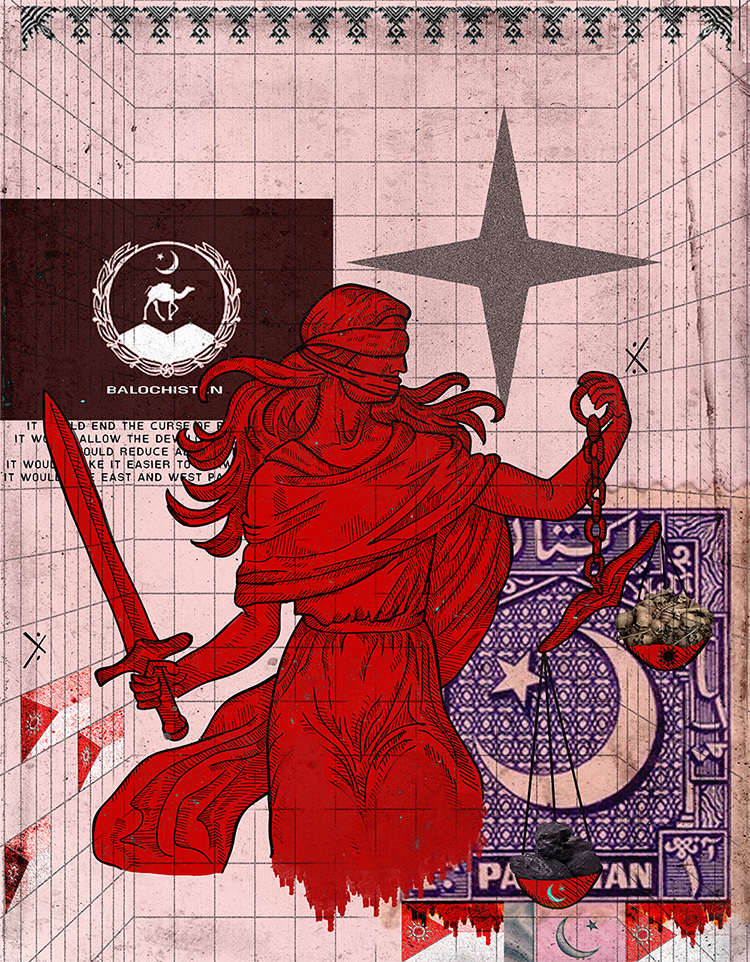

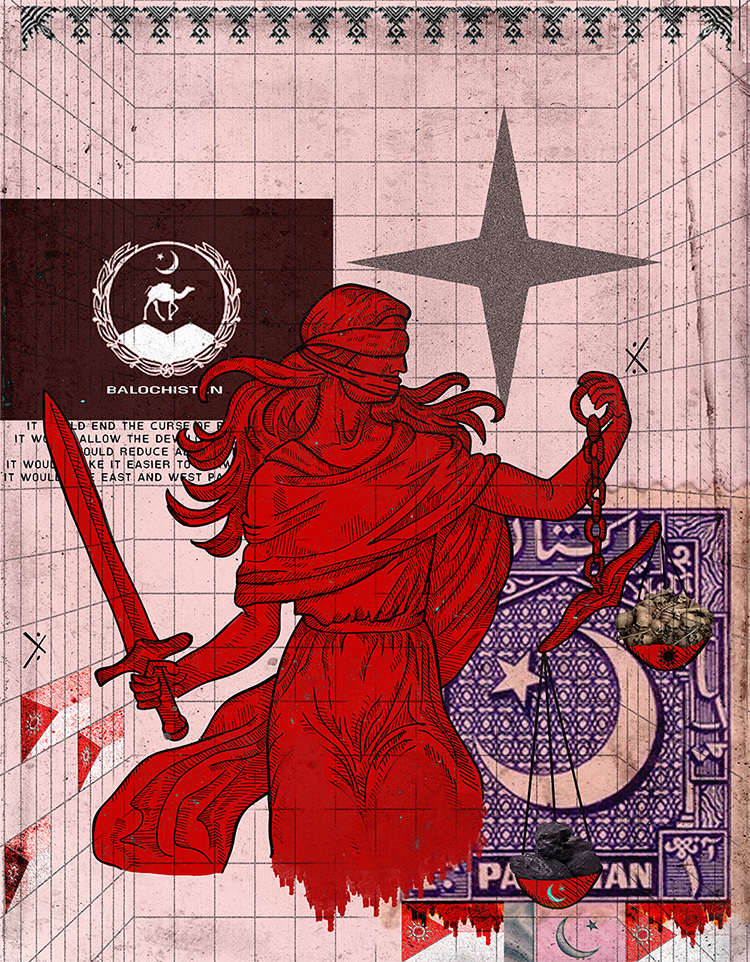

Graphic by Ayesha Rahmi and Hamza Saqib

The recent historic march of Baloch women, spearheaded by Baloch Yakjehti Committee (BYC)’s leader Mahrang Baloch, evoked memories of the 2014 Long March for me. The march was the first march of this sort in which participants were covering such a huge distance on foot, led by elderly Mama Qadeer and women and children from the families of missing persons. Speaking about Balochistan, let alone bringing to light the issue of its missing persons was unthinkable at the time. I was the Central Organizer of the National Students Federation at that time, and the march left an indelible mark on the collective consciousness of student organisers. Welcoming Mama Qadeer at the Karachi Press Club, and later joining the march from Jhelum to Islamabad, was not just a political act, but a deeply personal experience.

To go years on end not knowing the whereabouts of your loved one, or find their mutilated bodies dumped somewhere, are personal losses that serve as microcosms of the larger struggle against oppression in Balochistan. The revelations of Sher Mohammad Marri, the leader of the Parrari Movement and founder of Baluch People’s Liberation Front (BPLF), in his 1980 interview with the BBC shed light on the systemic injustices faced by the Baloch people, including the harrowing exploitation of young Baloch women during Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto's era.

Such historical injustices, compounded by the failure of Pakistan's judicial system to provide redress for victims of enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings, fuel the ongoing movement for justice and accountability in the province.

This year’s march represented the culmination of decades of grievances of the Baloch people against the state apparatus. Balach Baloch's abduction and extrajudicial killing, akin to the extrajudicial killing of Naqeeb Ullah Mehsud, galvanised a powerful campaign against state-sponsored violence, serving as a potent reminder of the urgent need for change.

Inherited from British colonial governance, Pakistan's legal system has often failed to prevent military interventions, martial laws, and military courts, perpetuating a cycle of impunity and injustice. This legacy of oppression and state violence underscores the urgency behind the Baloch women's march and the need for a critical examination of Pakistan's judicial system.

As a political organiser, I believe understanding the current movement requires delving into the history of enforced disappearances in Balochistan, the most disturbing form of violence, and the judicial system’s failure.

The Plight of the Baloch

In the 1910s, Noora Mengal emerged as a courageous leader in the Baloch resistance against British colonial rule. His defiance came at a steep cost. The date of his arrest at the hand of the British authorities is unconfirmed however, he died in prison in 1921. The British authorities withheld his body, denying his family a proper burial.

Although the British left the subcontinent in 1947, colonial oppression in Balochistan did not cease. The Baloch continued to be treated as colonial subjects after the unpopular and controversial annexure of Kalat with Pakistan in 1948.

The 1970s witnessed a surge in state-sponsored violence, with individuals like Shafi Shaheed, Dilip Daas, and Asad Mengal falling victim to enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings by security forces. Hameed Baloch's story is just one example of the ‘justice’ that is meted out to countless Baloch families. In December 1979, during a recruitment camp for the Royal Army of Oman in Turbat, Hameed was arrested under dubious circumstances after a gunshot was heard. Despite scant evidence, he was accused of murder and swiftly sentenced to death by a military court.

Advocate Mubasher Qaisrani, who represented Hameed's family, exposed glaring inconsistencies in the case, including discrepancies in the FIR and the lack of a credible post-mortem report. Despite legal challenges and a stay order issued by Chief Justice Khuda Bakhsh Marri, Hameed's execution was carried out on June 11, 1981.

The dawn of the 21st Century ushered in a new wave of violence against Baloch activists, with individuals like Ali Asghar Bangalzai becoming tragic symbols of the ongoing struggle for justice. Organisations like the Voice for Baloch Missing Persons (VBMP) and the Baloch National Movement (BNM) have documented thousands of similar cases, painting a grim picture of state-sponsored repression and impunity.

Commission of Inquiry On Enforced Disappearances (COIED)

The Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances (COIED) was established by the Ministry of Interior in March, 2011. It was supposed to serve as a crucial mechanism for investigating cases of enforced disappearances and promoting accountability. Headed by retired judges and bureaucrats, the COIED operates under the framework of the Pakistan Commissions of Inquiry Act, 1956.

Formed in response to the escalating concerns about enforced disappearances in Pakistan, the COIED holds several primary objectives. These include investigating and verifying facts related to enforced disappearances, uncovering the truth about individuals involved in serious human rights violations during armed conflicts, fostering an environment of sustainable peace and reconciliation, providing identity cards and compensation to victims of armed conflicts, and recommending legal sanctions against those responsible for such violations.

The formation of the COIED was viewed as a significant step by the government to address the issue of enforced disappearances. However, despite its mandate and efforts, the commission has faced criticism regarding its effectiveness and independence.

According to Imran Baloch, a lawyer from Quetta who has dealt with more than 75 missing persons cases since 2014, the “commission is a toothless entity, lacking the authority or will to hold perpetrators accountable.”

Similarly, renowned Supreme Court (SC) lawyer Faisal Siddiqui, appointed by the SC as amicus curiae to the court in the matter does not hold a favourable opinion of the commission. In an article published in Dawn, on December 23, 2023, Siddiqui wrote that the “commission has become a clearing house for the rationalisation and stabilisation of this unconstitutional injustice.”

One of the primary criticisms levelled against the COIED is its lack of enforcement powers as a commission of inquiry. Despite numerous recommendations and directives issued by the COIED, state agencies have routinely ignored or disregarded its findings, rendering its investigative efforts largely futile. While hearing cases pertaining to the issue of enforced disappearances, Justice Raja Fayyaz Ahmed cited the commission’s report in which it directed the government to compensate the families of the missing persons. He noted that the “government appears to be helpless before the spy agencies.”

Advocate Imran Baloch claimed the inquiry commission has members with military affiliations on it, undermining its ability to deliver credible information. Another criticism levelled by him, and corroborated in Rahim Baloch’s 2020 report for News Intervention, is that COIED does not allow legal representatives to appear in the commission and the families of victims are forced to plead their cases themselves.

Furthermore, Imran stressed that the commission's reliance on testimonies and evidence provided by state agencies, including the intelligence services accused of perpetrating enforced disappearances, has raised concerns about the integrity of its investigations. Without independent verification mechanisms or access to classified information held by state agencies, the lawyer believed that the COIED's findings remain subject to manipulation and distortion.

Despite these criticisms, the COIED continues to operate as the primary government body tasked with addressing enforced disappearances in Pakistan.

Judicial Failure and Political Exploitation

Balochistan is a semi-tribal society where maldevelopment under British and Pakistani rule is a commonly-aired grievance. The province’s general population has consistently demonstrated a prevailing reluctance to engage with Pakistan’s formal judicial system. In the early period of enforced disappearances, and to this day in some areas, people are found refraining from reporting missing person cases or seeking legal recourse.

The judicial system, meant to uphold the rule of law and protect citizens' rights, has failed to act as a mediator between the people and the state of Balochistan. Judges believed to be influenced and instructed by the powerful quarters have turned a blind eye to cases of enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings.

Mainstream political parties seem to have provided no alternative. Routine promises of justice and accountability are followed by more inaction. Bills aimed at addressing these issues have claimed to have vanished without a trace, highlighting the pervasive culture of impunity that pervades Pakistan's corridors of power. Recently, when the SC inquired about this matter, the Senate, after around two years of the allegation, maintained that the bill “never went missing”.

These hollow actions by the state are what made the BYC and the families of missing persons realise that the government is not serious about addressing the issue of enforced disappearances.

Police Inaction

The struggle for justice in Balochistan is further complicated by the failure of law enforcement agencies, particularly the police, to adequately investigate cases of enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings.

Despite legal obligations and international human rights standards, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, mandating thorough investigations into such gross violations, the authorities have consistently failed to fulfil their duties.

Under Section 154 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898 (Cr. P.C.), the police are required to immediately register an FIR detailing the nature of the offence upon receiving a report of a crime. However, there is no obligation for the police to investigate the incident, and they often exercise broad discretion in deciding whether to do so. Consequently, in many cases across Balochistan, FIRs are either not filed by the police or are poorly prepared, depriving victims and their families of even the most basic form of legal recourse.

The case of Sangat-Sana Baloch, documented by Human Rights Watch (HRW) and many other organisations, highlights the callousness of law enforcement agencies in addressing enforced disappearances. Despite clear evidence implicating security agencies in his abduction, the police at the Kalpur station refused to register an FIR, citing their inability to act against powerful entities. Similar instances occurred in the cases of Chakkar Khan Marri, Najeebullah Qambrani, and Zakir Majeed Baloch, where police officials rejected FIR applications or omitted crucial details implicating state actors.

Even when pressured by the SC to register FIRs, police officers have been reluctant to investigate disappearances allegedly committed by intelligence agencies or paramilitary forces. Families are told that the police lack the authority or jurisdiction to probe such cases, effectively shielding perpetrators from accountability and perpetuating a culture of impunity.

As families continue to grapple with the anguish of uncertainty, the systemic failures of the criminal justice system underscore the urgent need for comprehensive legislation for judicial reforms and accountability mechanisms. Holding perpetrators accountable and ensuring access to justice requires serious efforts from the legislature, which is often impeded by the influence of the military establishment according to the HRW report on enforced disappearances. All of these systemic failures are resulting in a weak judicial response to the issue of disappearances.

Weak Judicial Response

Pakistani law recognizes the internationally protected right to habeas corpus, which is the right to be brought before a court and challenge the legality of one’s detention. This is a crucial procedural guarantee against enforced disappearances and unacknowledged detention. In cases of alleged abductions or unlawful detention by the security forces, a provincial high court has the power to compel the detaining authority to produce the detainee before the court to verify the legality of the arrest, regardless of who detained the person.

In Balochistan, and across Pakistan, the practical application of the right to habeas corpus has been severely compromised. Reports from HRW indicate that both judicial reluctance and security agencies' defiance have eroded its effectiveness. This systemic failure to address enforced disappearances has drawn consistent condemnation from national and international human rights bodies.

For years, agencies and government bodies that have the power to exercise institutional control over them have openly defied and misled the courts in habeas corpus hearings. In 2006, the Defense Ministry stated that it had only administrative, but not operational, control over the intelligence agencies, and thus could not produce the detainees in court. Similarly, LEAs have routinely ignored court orders to produce detainees.

The SC has often ruled that the burden of proof lies with the detaining authority to justify the legality of an arrest or detention. However, in practice, security agencies have not been held to this standard.

However, there are few judges, such as former CJPs Iftikhar Chaudhry and Jawwad Khawaja, as well as Justice Athar Minallah and Justice Mohsin Akhtar Kayani, who have shown the courage to advocate for the missing persons. Nevertheless, Faisal Siddiqui admitted in his article, The Missing Baloch, that their pens have been defeated by the sword. In the same article, Siddiqui clearly asserted that there is no legal solution, and the hopes that are being fostered are merely a "false dawn."

The SC, with a bench headed by CJP Qazi Faez Isa, recently revisited the issue of missing persons. The hearing led to the Senate in locating, if not the missing persons, then at least the ‘missing bill’ on enforced disappearances. When asked whether there was hope at the end of the tunnel or if the hearings were just another false dawn, Siddiqui responded succinctly, saying, "it all depends on the next date of the hearing."

As per Advocate Imran Baloch, "Unfortunately, the SC continues to neglect proper legal procedures and rationale necessary for resolving the issue of missing persons. Ex-caretaker prime minister Anwaar-ul-Haq Kakar ignored IHC summons at least twice in the missing Baloch students case, and the court did not issue any contempt notices. He even made contemptuous statements against the judiciary. The SC's failure to issue contempt notices highlights the perception that even the apex court faces limitations due to the issue beingframed as a matter of national security.”

BYC’s Stand on International Engagement

More than before, the BYC now appears to be taking a strategic approach to appealing to the UN and other international bodies to address the matter of “Baloch genocide”. This move, albeit expectedly unsettling for Islamabad, has emerged as a step out of necessity given the limited avenues available to the Baloch citizens.

The families of the missing persons, spanning across generations from children to the elderly, encountered numerous difficulties in staging the recent sit-in outside the Islamabad Press Club. The participants complained of the police preventing access to vital supplies such as food, tents and blankets to the protest camp, creating obstacles for journalists and human rights activists in covering the sit-in, and launching a smear campaign against the women leading the march. Moreover, a rival camp sprung up overnight near the one established by the protesters. The camp, which activists said was established by the state and occupied by members of death squads from Balochistan, was provided with facilities denied to the marchers.

Dr Sabiha Baloch, a prominent figure of BYC Shaal who spearheaded the march from Turbat to Quetta, emphasised that by turning towards the UN and the international community, the BYC has highlighted the futility of relying solely on Pakistani state institutions. The movement's pivot towards international engagement aimed to fortify domestic resistance while highlighting Balochistan's plight on a global stage.

According to Dr Mahrang, the protest and the ensuing march began with the demand for an FIR against those accountable for the extrajudicial killing of Balach. However, the state's response was dismal. “The authorities instead began fueling propaganda against Balach, attempting to label him a terrorist.This left the BYC with only few alternatives,” she said. “It was not merely about a single case but about the oppressive and ruthless measures that the entire Baloch community faces,” Mahrang added.

She further stated, “the urgency and gravity of the situation and the state's response compelled us to approach the international community.” “Even in our communication with the UN, we highlighted that the families of missing persons have multiple times engaged in dialogue with state authorities, such as after the 2022 sit-in and subsequent negotiations. Yet the state never fulfilled its commitments. Engaging with the UN became necessary to sustain mobilisation around the issue and depict enforced disappearances as an international concern, because it assumes international dimensions when the state of Pakistan is directly involved in these atrocious crimes and its institutions have failed to redress these grievances."

In January 2024, Dr Mahrang, along with another prominent BYC activists Sammi Deen Baluch, met officials from the UN Mission to Pakistan to urge for a UN-led probe into the issue of enforced disappearances.

The BYC leaders maintained that by engaging with the international community, the issue was transformed into one concerning the entirety of Balochistan and not solely the 300 families of missing persons staging the sit-in in Islamabad. They remain optimistic that international organisations will dispatch fact-finding missions to Balochistan and aid in bringing these issues and their true nature to light before the world.

To date, there is a lack of precise figures regarding missing persons. Additionally, forms of state oppression and violence such as cultural suppression have yet to be addressed.

The Path Forward: Use, Subvert, and Change

Most marginalised communities in Pakistan stress the need for engaging with international organisations and international laws.

Karachi has witnessed similar injustices perpetrated against vulnerable communities, where efforts to seek legal recourse through local institutions have often been met with insurmountable barriers and systemic biases. The dismissal of stay orders without due consideration of the leases held by affected individuals of Gujar and Orangi Nullah demolitions exemplifies the challenges encountered in seeking justice through established channels.

Under such circumstances, the decision to engage with the UN and other international bodies gains significant value. While tangible outcomes may be elusive in the short term, international engagement serves multiple purposes that are integral to the broader struggle for equality, justice, and freedom.

However, I believe it's crucial to recognize the limitations and complexities of international engagement as well. Historically, oppressed nations like Palestine, and Kashmir have faced disappointments in seeking redress through international forums.

Despite these challenges, a third path forward emerges, as proposed by Muhammad Azeem: the marginalised of the Third World are to simultaneously use, subvert, and change the form and content of international law in a dialectical and dynamic way. This approach acknowledges the inherent flaws of the existing system while advocating for strategic engagement to challenge and transform it. By leveraging international mechanisms, marginalised communities can amplify their voices, expose injustices, and demand accountability while also working towards reshaping international norms and standards to better serve their interests.

Khurram Ali is a former central organizer of the National Students Federation (NSF) and ex-general secretary of Awami Workers Party (AWP) Karachi, currently serves as the Convener of Karachi Bachao Tehreek (KBT). For inquiries, contact via email: k.a.nayyer@gmail.com. Connect on X: @AliMantiq.